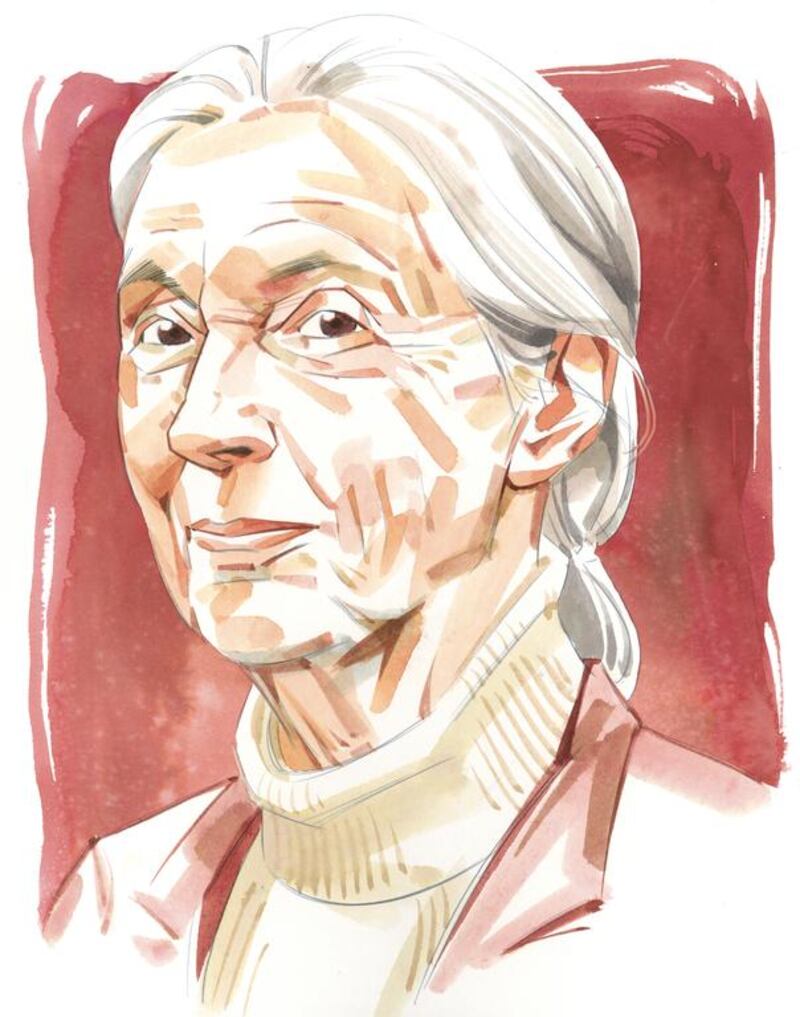

Chickens and chimps might not have a lot in common. But it was while studying the former as an inquisitive 5-year-old that Jane Goodall first demonstrated the incredible patience that would later establish her as the world’s foremost expert on chimpanzees.

In her 2007 autobiography, My Life with the Chimpanzees, Goodall recalled hiding in the henhouse in the garden of her family home in England, determined to discover how chickens produced eggs.

She emerged hours later, triumphant, only to discover her mother was about to call the police to report her missing.

“I had an understanding mother,” Goodall later recalled. “Instead of being angry, she wanted to know all about the wonderful thing I had just seen.”

Later, among the chimpanzees in the Gombe Stream National Park, in what was then Tanganyika, Goodall would see many more wonderful things.

Over the years she was to spend at Gombe, she would establish that chimpanzees were not, as had been thought, vegetarians, and that to each other they could be “just as awful” as human beings.

Most astonishingly, though, the years of patient observation paid off when she became the first person to witness a chimpanzee making a tool.

Today, Goodall’s fame as the world-leading expert on chimpanzees has spread far beyond academe. What other primatologist can claim to have been parodied in The Simpsons or gently mocked in a Gary Larson cartoon?

In 1977, she founded the Jane Goodall Institute, initially to raise awareness of the plight of chimpanzees but whose mission has evolved “to empower people to make a difference for all living things”.

In 1991, Goodall created Roots & Shoots, a global environmental and humanitarian youth programme, which now has more than 150,000 members in over 130 countries.

She has been feted and honoured all over the world. Appointed in 2002 as a United Nations Messenger of Peace, in 2004 she was made a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire and in 2006, she was awarded France’s Legion of Honour.

Since 1986, Goodall, who will be 81 this April, has pursued an exhausting schedule. She spends 300 days on the road each year, lecturing, arguing for conservation with officials around the world and meeting the young members of her Roots & Shoots movement – the reason for her talk at NYU Abu Dhabi next week.

As remarkable as her life’s work has been, however, one of her greatest achievements was as a young woman, when she refused to let a lack of either money or a university education stand in the way of realising her dream of working with animals.

Her love of animals began, she has said, when she was 7 and her mother gave her the children's novel, The Story of Doctor Dolittle.

John Dolittle, who lives a quiet life in the fictional sleepy English village of Puddleby-on-the-Marsh, is taught by his pet parrot to communicate with animals and sets off for Africa to cure an epidemic among monkeys.

Goodall had “never before loved a book so much”. That, she later wrote, “was when I first decided I must go to Africa”.

It would be easier said than done.

When she finished school at 18, her mother and father, who by now had separated, could not afford to send her to university. Instead, Goodall trained as a secretary, working for a physiotherapist in her hometown of Bournemouth.

The call of the wild, however, soon brought her to London, where she worked for a documentary film company while spending much of her free time in the Natural History Museum.

“I knew that it was just filling in time,” she later wrote. “Always I was waiting for my lucky break.”

It came in the shape of a letter from an old school friend, inviting her to visit her family farm in Kenya.

Goodall raised the money for the trip by working long hours as a waitress in a hotel. In 1957, at the age of 23, she set sail on the Kenya Castle for the 21-day journey to Mombassa.

In Kenya’s close-knit British colonial society, she was soon introduced to Louis Leakey, an anthropologist and palaeontologist whose secretary had just quit. The meeting would change Goodall’s life.

Leakey took her on. He was, Goodall recalled, “impressed by how much I knew about African animals”.

Soon, she would know much, much more.

Leakey was fascinated by a group of chimpanzees that lived on the shore of Lake Tanganyika. They might, he believed, hold clues to the way our ancestors had lived and he was looking for someone to study them.

Goodall, utterly unqualified, “had not imagined that I could be chosen but I desperately wanted to try”. To her surprise, Leakey leapt at the idea, delighted to be able to send someone whose mind was “uncluttered by theories”.

While Leakey set about raising funding, Goodall returned to England to learn what she could about chimpanzees. A year later, at 26, she returned to Africa with her mother – the authorities insisted she had a chaperone – and on July 16, 1960, she set foot on the shore of the lakeside Gombe Stream Game Reserve for the first time, embarking on a lifelong relationship with chimpanzees.

The work was tough, often lonely – her mother returned to England after four months – and frequently dangerous, thanks to wild animals, poachers and rebels in the neighbouring Belgian Congo.

It was a year before the chimps would even let her get within 100 metres, a breakthrough that came only after Goodall shrugged off her ranger guard and insisted on going into the forest alone.

There, sitting on a peak overlooking the reserve, she began to gather the data that would alter our understanding of the relationship between humankind and primates.

One day, she saw a chimp she had named David Greybeard stripping the leaves off a twig and using it to fish termites out of a mound.

“He had actually made a tool,” she wrote. “Before this observation scientists had thought that only humans could make tools.”

Goodall also discovered love in the forest. National Geographic, which by now was sponsoring the research, sent the Dutch photographer Hugo van Lawick to document her work. He “loved and respected animals just as I did”, Goodall wrote, and one year later they married.

Wherever she is in the world, in her mind Goodall never strays far from her heartland – Gombe – to which she returns twice a year.

"Sitting up on the peak where I sat as a young woman, I still get those same feelings of excitement I had then," she told BBC Radio's Woman's Hour in 2012.

“I spent so many years there on my own with the chimps, out in nature, and I just felt so strongly this great spiritual power.”

Goodall’s life has not been without controversy. Early in her career she was criticised by the science establishment for naming, rather than numbering, her chimpanzee subjects. This, it was felt, would lead to the scientifically undesirable anthropomorphising of the creatures.

But she has always had far more fans than detractors.

Mary Smith, a former editor of National Geographic, who wrote the foreword to Goodall's 1999 book, 50 Years at Gombe, described her as "extraordinary … a superb scientist and a genuine heroine in a world crowded with hero wannabes".

Today, at the age of 80, Goodall knows the future of the planet is in the hands of a new generation of heroes, and she puts her faith in children, such as those she will meet next week in Abu Dhabi.

“It is the young people who give me the most hope,” she has said, and for them she has a simple, stirring message.

“If we are the most intellectual creature that’s walked on the planet, how come we’re destroying that planet?

“We must learn to live in peace and harmony, not only with each other, but also with the natural world.”