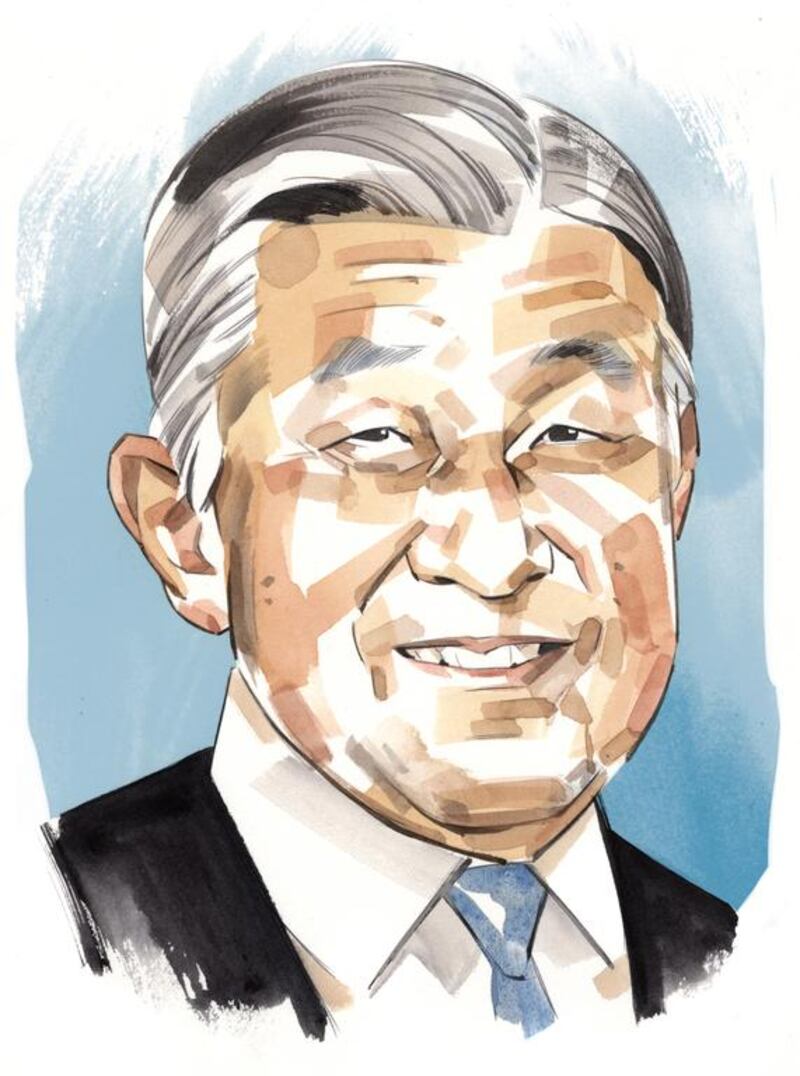

In June, the Japanese national rugby team played host to Scotland for two Tests. After the home side lost to the Scots in the first, news filtered through that the home side would be playing the second match in front of Japan’s Emperor Akihito and Empress Michiko.

It was the first time the Imperial Couple had attended a Japan Test match. The prospect of recording a victory in front of two individuals revered above all others in Japan thrilled the national team. While Scotland won against their clearly fired-up opponents, they did so only just, after a second-half comeback, such was the honour for the Cherry Blossoms to play in front of their emperor and his wife.

When Emperor Akihito announced this week his wish to one day step down from his role as symbol of the state – confirming media reports from last month – the shock waves took little time to spread beyond Japan.

The emperor’s indication of his wish to abdicate was not expressed in the traditional sense, however. Forbidden to directly announce his desire to bring an end to his near 30-year reign, lest it bring him into direct conflict with the Japanese constitution, the 82-year-old’s address to the nation was an attempt to win the sympathies of a public that had only once before heard their emperor make a televised address. Referencing his health problems and age, Emperor Akihito asked his people for their “understanding”.

“As I am now more than 80 years old and there are times when I feel various constraints such as in my physical fitness, in the last few years I have started to reflect on my years as the emperor, and contemplate on my role and my duties as the emperor in the days to come,” he began.

“In coping with the ageing of the emperor,” he continued, “I think it is not possible to continue reducing perpetually the emperor’s acts in matters of state and his duties as the symbol of the state.

“With this earnest wish, I have decided to make my thoughts known,” he concluded, leaving Japan in little doubt as to his preferred goal.

His historic remarks weren’t lost on Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, who as head of government has found himself leading a nation that has been given the mother of all constitutional jolts.

“Upon reflecting how he handles his official duty and so on, his age and the current situation of how he works, I do respect the heavy responsibility the emperor must be feeling and I believe we need to think hard about what we can do,” Abe stated.

With public support – according to the Kyodo News agency, 85 per cent back the legalisation of royal abdication – this very human, bookish monarch, whose emperor father was viewed as divine, may well witness his eldest son take up the limited powers of the Japanese throne. And in doing so, he will open up this ancient monarchy to a new era of constitutional change.

The octogenarian emperor was born in Tokyo on December 23, 1933, into the oldest continuous hereditary monarchy in the world. As the eldest son of Emperor Hirohito and Empress Nagako, Akihito was in line to assume the throne from birth. As per Japanese royal tradition, a young Akihito was separated from his parents to be raised by guardians in an imperial nursery.

He began his education at the exclusive Peers’ School in Tokyo in 1940, but was evacuated from the capital to outlying areas towards the end of the Second World War. His education included instruction on western customs and the English language – as well as lessons in diplomacy. He studied political science and economics at Gakushuin University, though he never received a degree.

With Japan in rebuilding mode after its costly defeat in the war – the nuclear obliteration of Hiroshima and Nagasaki apart, the young prince reportedly expressed shock at seeing Tokyo’s destruction on his return to the capital as a young boy – Akihito was formally bestowed with the title of crown prince in 1952. Officially in line to become the 125th emperor of a nation that can trace its monarchy back more than 2,600 years, Akihito was now able to strut the world stage. And he did so across the United States and Europe – most notably in 1953, when he attended the coronation of the British monarch, Queen Elizabeth II, on behalf of his father.

In 1959, Akihito blazed a trail when he ended an ancient Japanese royal tradition by marrying a commoner. Dubbed the “tennis-court romance” on account of their meeting at a tennis club in a high-class mountain resort, the love-match apparently set off a nationwide tennis obsession. Michiko Shoda was the daughter of a company president, and by all accounts, much sought-after. The graduate’s marriage into the Japanese royal family sent her public profile into the stratosphere.

Akihito’s father died on January 7, 1989. Following various rituals, which included dedications at the shrine of the Sun goddess Amaterasu, the crown prince officially ascended to the Chrysanthemum Throne on November 12, 1990.

As emperor, Akihito ushered in a new era of “Heisei” – or “Achieving Peace” – in a modern country where, as part of Japan’s terms of surrender following the Second World War, Emperor Hirohito had been forced to disclaim his divinity. Relegated to a purely symbolic position, the still-revered role of emperor took on a more humanitarian guise under the reign of Akihito, the first Japanese monarch to ascend to the throne as merely a supremely privileged man.

Akihito’s acts as emperor have encompassed international visits and a wish to heal the wounds of the Second World War. Foreign engagements have also included the emperor’s 2007 hosting of Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi and Deputy Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces, during which Akihito spoke of the visit to Japan as adding “more vibrancy to the UAE-Japanese relations, which are getting stronger day by day”. Sheikh Mohammed followed up with another visit in 2014.

In essence, and in a seismic departure from Japan’s ancient royal past, Akihito’s reign has also been publicly marked by some very personal concerns. In 2003, three years after the death of his mother, Akihito underwent surgery for prostate cancer. He went under the knife again in 2012, when he had coronary artery bypass surgery.

Empress Michiko, who has given her husband three children, has found that the trappings of imperial wealth and power haven’t made for a serene existence.

From the beginning, and despite her marriage-match to the then crown prince being agreed, she wasn’t easily accepted into the royal family by Akihito’s parents. A bright and well-educated woman, Michiko’s world became one of tradition and, as she has admitted, a real loneliness.

“It has been a great challenge to get through each and every day with my sorrow and anxiety,” said the empress during a news conference in 2007.

Many in the wider world may have believed that Japan’s royal family had disappeared years ago, so low was their profile until Akihito delivered his first televised public address following Japan’s destructive earthquake in 2011. Before this event, it was Emperor Hirohito who had sent shock waves through the country, when on August 15, 1945, he made a radio address announcing the surrender of Japan, a week after the atomic destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

More than 65 years passed until a natural disaster proved traumatic enough for Akihito to follow in his father’s footsteps and present himself to his own people and a curious international audience.

“I hope from the bottom of my heart that the people will, hand in hand, treat each other with compassion and overcome these difficult times,” the emperor said at the time.

A keen amateur marine biologist who has a species of goby fish named after him, Akihito has presided over a very different, non-confrontational Japan to the country that fought and lost a war under his father. Yet with no means for him to abdicate, any changes to achieve such an outcome would have to be approved by parliament.

While it appears that the majority of the Japanese people sympathise with their emperor’s wish – “If the emperor needs to abdicate, then we feel his majesty should be respected,” one Japanese citizen told the BBC – many on the nationalist right are holding fast to the notion that Akihito’s role can only end when he dies.

In a country that hasn’t witnessed a royal abdication since that of Emperor Kokaku in 1817, the very human Akihito is finding that any wish to make plans for his retirement is bringing up its very own kind of human problems.

weekend@thenational.ae

Follow us @LifeNationalUAE

Follow us on Facebook for discussions, entertainment, reviews, wellness and news.