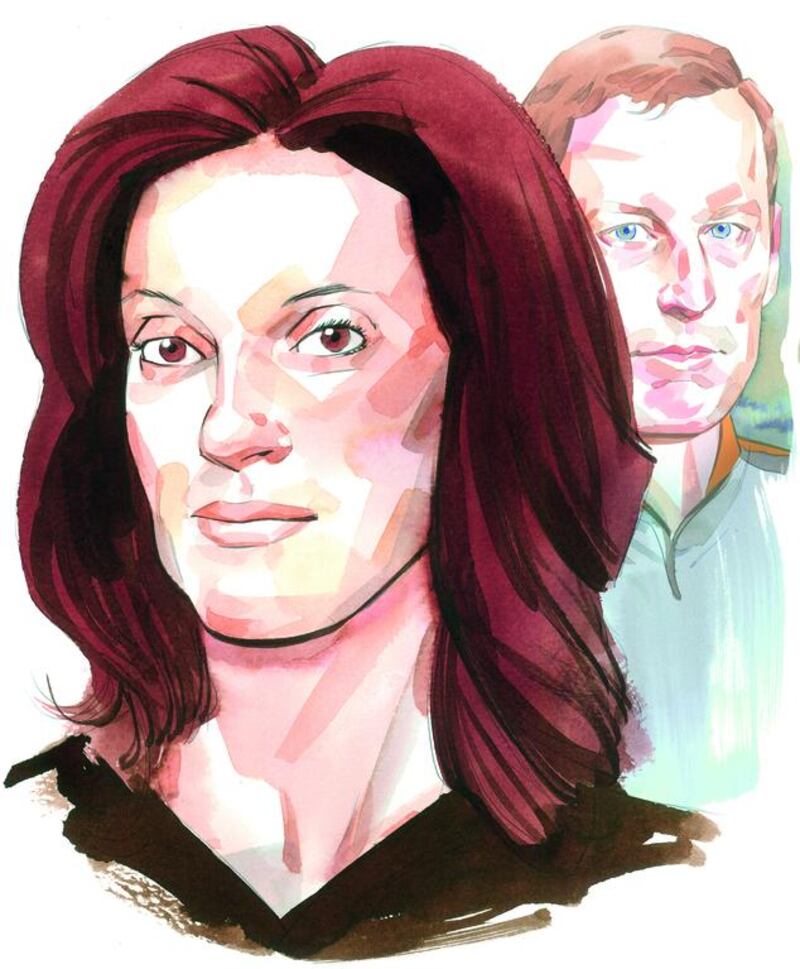

When she dared to speak ill of America’s sporting sweetheart Lance Armstrong, Emma O’Reilly was publicly branded a prostitute, an alcoholic and a liar.

The fuss that followed her allegations that Armstrong’s cycling success was as much down to doping as it was to his impressive cadence, pretty much destroyed her career and reputation. She stayed out of the spotlight for almost a decade but re-emerged when Armstrong eventually admitted his crimes. She has now published a tell-all book, explaining her role as the original whistle-blower.

O'Reilly was dragged through the courts for more than two years by Armstrong, 42, after her claims were published in LA Confidentiel: Les secrets de Lance Armstrong, an exposé written by the sports journalists Pierre Ballester and David Walsh, of The Sunday Times, in 2004.

Unsurprisingly, the book didn’t go down well with Armstrong, who at the time was celebrating his sixth straight Tour de France win, supposedly drug-free.

He tried to sue virtually everyone involved in its publication, and any newspaper or magazine that had the audacity to print any of the damning excerpts. One of his main targets was his former right-hand woman, O’Reilly, 43, who had worked closely with him for four years.

The book included claims from O’Reilly that she had been asked by Armstrong to dispose of used syringes, and on one occasion was told to find him make-up to help cover up needle marks on his arm.

O’Reilly was in her 20s when she started working with Armstrong. In her four years with the US Postal Service Pro-Cycling Team, Armstrong won two consecutive Tour de France titles; he went on to win a further five, breaking the record for the most consecutive wins. He was later stripped of all seven titles.

The annual Tour de France, started in 1903, is the oldest and most prestigious of the three Grand Tours. This year’s race, which started on July 5 and finishes in Paris on July 27, covers 3,500 kilometres.

In 2005, after Armstrong’s seventh win, he was, on paper at least, the best cyclist the world had ever seen.

O’Reilly, a Dubliner, had moved to the United States after winning a Green Card lottery in 1994, just a few weeks before her 24th birthday. She had previously been working at the Irish national team as a part-time masseuse.

Two years after moving to the States, she landed the job of soigneur with the US postal team, of which Armstrong was a clear star. Soigneur, while sounding rather fancy, refers to a person who gives “training, massage, and other assistance to a team”, according to Oxford Dictionaries. This “other assistance” can refer to anything from cleaning kit to preparing meals. It does not, of course, include helping athletes cheat their way to the medal podium.

O’Reilly, who had left school at 16 to become an electrician, was clearly a well-liked member of the team. Tyler Hamilton, an American former professional bike racer and Olympic gold medallist, described O’Reilly in his 2013 book about doping as “whip-smart and funny to boot”.

But in 2000, she quit the team and the sport altogether. Her departure was without any public fanfare. She kept what she had learnt about doping close to her chest, choosing to sit on the information for four years until she gave an interview to The Sunday Times's award-winning sports correspondent Walsh, who collected a number of other interviews to include in his book. Inevitably, it opened a huge can of worms.

Armstrong said all the allegations of doping were fantasy and embarked on suing various parties for defamation. He dropped the case against O’Reilly after a couple of years. But by that time O’Reilly had had enough of the Team Armstrong onslaught and slipped off the cycling radar altogether.

Armstrong had won the battle, silenced most of his critics and continued to compete professionally.

His harsh treatment of O'Reilly after LA Confidentiel – which included publicly raising rumours about sexual promiscuity and alcohol – was enough to keep the strongest of critics quiet. And stay quiet she did. For almost a decade.

But even during her silent years it was hard – maybe impossible – to disentangle the stories of Emma O’Reilly and Lance Armstrong. O’Reilly probably always will be known as the woman who blew the whistle on a great national treasure. She doesn’t have her own Wikipedia page but is cited on the page for the “History of Lance Armstrong doping allegations”. There is very little personal information about her in the public domain, but a search for her name pulls up hundreds of links to pages written about her important role in Armstrong’s downfall.

It’s safe to assume that when she decided to speak out all those years ago, she didn’t fully appreciate the fury that was about to roll her way in the form of public shamings, name-calling and lawsuits. She had been brave, if a little naive.

But this is understandable given that she hadn't grown up in the spotlight, and she wasn't from a famous sporting family. In her new book, The Race to Truth: Blowing the Whistle on Lance Armstrong and Cycling's Doping Culture, she admits: "The past decade has made me media-savvy, something I most definitely wasn't at the start of this journey."

In 2012, she gave sworn testimony about her time with the team to the United States Anti-Doping Agency (USADA). Armstrong, on the other hand, declined to “come forward and be part of the solution”, according to the agency. Instead, it was left to 11 of his teammates to reveal the ugly truth.

Using the evidence from O’Reilly and the rest of the witnesses, the USADA determined in late 2012 that the US Postal team “ran the most sophisticated, professionalised and successful doping program that sport has ever seen” and handed Armstrong a lifetime ban. In January 2013, after trying to fight his ban, Armstrong decided it was time to hold his hands up and say sorry to those he’d damaged or hurt – including O’Reilly.

He used a two-part interview with Oprah Winfrey to explain and apologise for his actions – including his behaviour towards O’Reilly.

“She is one of those people that I have to apologise to,” he said, adding that she was also one of the people that got “run over” and bullied.

Even after his public apology, O’Reilly wasn’t afraid to speak her mind, and admitted that she didn’t find his stint with Oprah particularly convincing.

In an interview aired on RTE One, the most-watched channel in Ireland, shortly after the Oprah revelations, O’Reilly said: “The sneer, it was like ‘oh Lance, you needed more practice’,” she said, possibly saying what many of us were thinking. “Lance, maybe I should have put something in your eyes to make them a bit weepy or something.”

When asked if she thought he was sorry, she was blunt. “He’s sorry he got caught, and he’s sorry he can’t compete … but he’s not sorry … not sorry at all,” she said.

It was clear all was not forgiven or forgotten. O’Reilly also said on another occasion that she was debating whether to take legal action for what had happened or just get on with her life running the private physiotherapy clinic she set up in Hale, England, more than eight years ago. She didn’t really do either.

Instead, she eventually kissed and made up with Armstrong, and went on to write her tell-all book, whose front cover features a photo of the pair of them. On the back cover is a photograph taken of them in late 2013, when a UK national newspaper organised for them to meet face-to-face for the first time in a decade.

And in a real twist, Armstrong has written the foreword to the book, in a move that will no doubt help The Race to Truth work its way up the sporting bestseller list. Some people would like to think O'Reilly has forgiven, if not forgotten, but those more cynical might consider the move a savvy, hopefully lucrative one.

On July 3, Armstrong tweeted that he was “honored and humbled” that he had been asked to write the foreword to the book. “She says what is right and what is wrong and for a time that worked against the lies I was telling the world,” he writes in the foreword, adding that she showed “enormous courage” for speaking out and trying to clean up the sport.

“Overnight my story as sporting hero and Tour de France champion went from a lily white picture to jet black. But, unlike many others, Emma doesn’t view it like that. She wasn’t going to sit there and say: ‘It’s black or it’s white’. She sees the cool shades of grey.”

Despite his kind words about O’Reilly, Armstrong couldn’t resist using the foreword to try to get a little bit of sympathy for his fallen career. “Yes, I doped,” he writes, “but from what I can tell, so did many pro-cyclists and while I’ve been banned for life, hundreds of others involved will go unpunished.”

munderwood@thenational.ae