When it comes to establishing defining episodes in history, moments of synchronicity come as manna to historians.

Places and times when the personalities and forces that appear to determine the course of events coalesce, as if by magic, around an organisation, an individual, a place or an event; they emerge, like moments of clarity, from the tumult of the past.

Art history is full of such episodes, which are used to explain the development of art movements and careers. Moments such as the late-imperial Vienna of Egon Schiele and Gustav Klimt, inter-war Paris at the time of René Magritte and Picasso and the post-war New York of Philip Guston and Jackson Pollock, all of which are now considered as canonical episodes in the development of western Modernism.

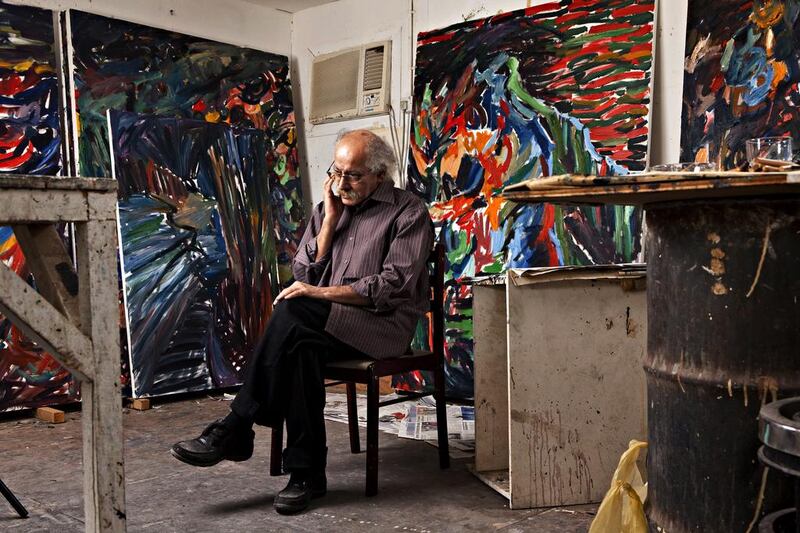

If the curators of the latest exhibition at the art gallery at New York University Abu Dhabi have their way, the artistic community that formed around Emirati artist Hassan Sharif (1951-2016) in Dubai during the 1990s and early 2000s will occupy a similarly important role in any future history of the UAE’s art.

However, But We Cannot See Them: Tracing a UAE Art Community, 1988-2008 almost did not take place.

After she heard of Sharif’s death last September, the NYUAD Art Gallery’s director and curator Maya Allison momentarily abandoned all thoughts of continuing with the show and the first-person interviews that form the core of the book that accompanies the exhibition.

“We were going to do the show and we’d got everyone’s permission and support and, then, after he died, I didn’t want to do it any more,” Allison tells me, still visibly upset by Sharif’s death.

“We’d just started doing the interviews and everyone was still reeling from the news, and I thought it might become too much like an homage,” says the curator.

“That’s not my place, but when I went back to people, everyone was really supportive and they just said, ‘Do it’.”

Allison’s interviewees include: artists Mohammed Ahmed Ibrahim, Abdullah Al Saadi, Ebtisam Abdulaziz and Mohammed Kazem, who studied under Sharif; the poets Khalid Albudoor and Adel Khozam; the filmmaker and poet Nujoom Al Ghanem; Vivek Vilasini, who originally arrived in Dubai from Mumbai; the Italian curator Cristiana de Marchi; and Sharif’s brothers, Hussein and Abdul-Raheem.

Pioneers who paved the way for the UAE’s contemporary cultural landscape, the visual artists at the core of this group – Hassan and Hussein Sharif, Kazem, Al Saadi and Ibrahim – are often popularly referred to as “the Five”, a name taken from one of the group’s earliest exhibitions, and are frequently credited as being at the forefront of conceptual art in the Emirates.

For Allison and the team behind But We Cannot See Them however, the history of art in the emirates is both richer and more complex.

"There was a show called The Four, there was a show called The Six, there were a couple of shows called The Five and there was even a show called The Seven, but there is no 'The Five', and even the shows called The Five didn't have the same artists in them," Allison insists.

Rather than overemphasising the role of Sharif’s Dubai-based community, Allison paints a picture of a multicentred and interconnected UAE art scene in the period, with key groupings in Sharjah, Khor Fakkan and even on a sand dune located on the border between Ajman and Sharjah, dubbed The Sand Palace, where a burning fire was used to indicate that the “facility” was in use.

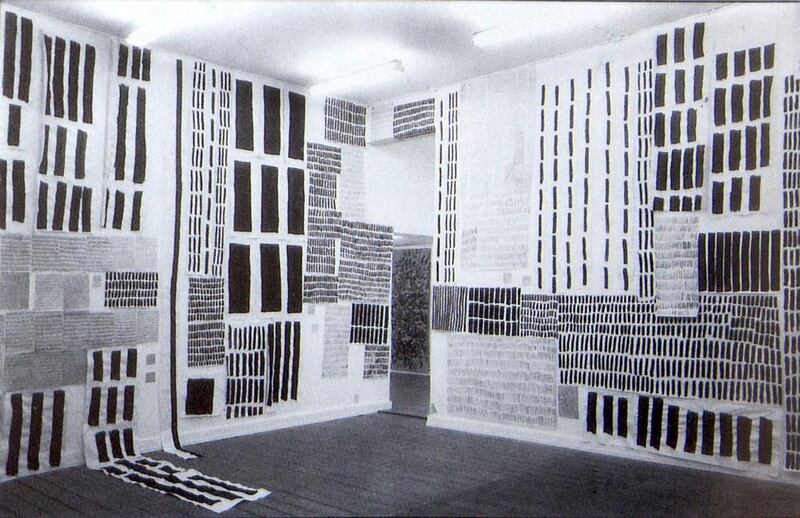

"The Sharjah Art Museum and the Emirates Fine Arts Society were among the few public places in the UAE where experimental artworks were exhibited at the time," Allison writes in her introduction to But We Cannot See Them. "Some of the UAE's most heated aesthetic debates, public and private, grew out of the exhibitions in Sharjah, particularly the more experimental, conceptual projects by artists in this group. Controversy followed a number of their exhibitions, and every now and then a piece of artwork would just disappear, seemingly mistaken for refuse."

The issue faced by this pivotal group of like-minded contemporaries was the lack of year-round exhibition spaces or publications that would make their work visible to a wider audience.

“They had their annual show at the Emirates Fine Arts Society and shows at the Sharjah Biennial,” says Allison. “But there wasn’t any consistent, year-round presence and they were also being lumped together with other people at that time.”

On an informal basis the group attempted to solve this problem by gathering in a salon in the courtyard of Hassan Sharif's ramshackle house in Satwa, Dubai, a location that also forms the focal point of But We Cannot See Them.

“I was really heartened to learn, back in 2012 or so when I first met Mohammed Kazem and Cristiana de Marchi and then some of the other artists, that there was a community that would hang out in the courtyard of Hassan Sharif’s house and have long conversations that could be about philosophy, about art, about his cat,” says Allison.

“Many of them identified with a ‘new culture’ of radical, formal, and conceptual experimentation in both art and writing. It is said that if you had a key to the house you were welcome any time, day or night, but it’s been really challenging to write about because nobody is an authority and even the artists disagree with one another about what they were and what they are,” she admits.

“Were they independent, were they avant-garde? They’re not a movement because they didn’t have a manifesto, they’re not underground because they were out there but nobody could see them, they’re not strictly avant-garde, they’re just friends who are taking refuge in each other and who are trying to be true to their art.”

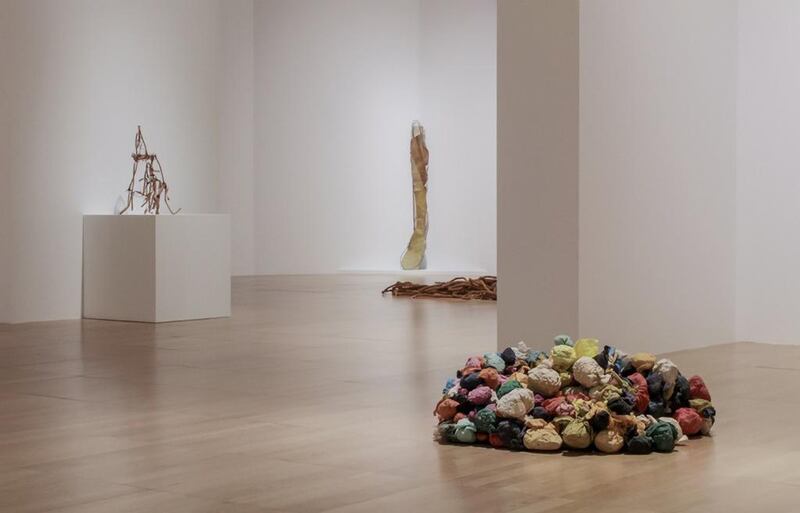

In curating the exhibition, Allison and her colleagues Bana Kattan and Alaa Edris have tried to ensure that they have included works from the group that were originally displayed together or that illustrate the conversations and debates in which they were engaged; however, as many of the works from this period have been lost or are housed in inaccessible collections, mounting an exhibition that shows the activity and the innovation of the period has been challenging, to say the least.

“We went on a studio visit with Mohammed Ahmed Ibrahim in Khor Fakkan,” Kattan remembers, “but whenever we would ask for anything he would say: ‘Yeah, that one’s gone. It’s lost. It’s gone with the wind.’”

Allison admits: “It’s a more literal way of showing the interactions, but we’ve done whatever it takes to start to see them. “You can also really see their differences and dialogue, and when you include the work of Jos Clevers and Vivek Valasani, which have been missing pieces from the narrative, it totally changes how you understand what they were doing.”

A Dutch sculptor and curator who arrived in the UAE in the early 1990s, Clevers came in search of authentic Emirati contemporary art, found it and within a year was exhibiting in the UAE and organising the group’s first international exhibitions.

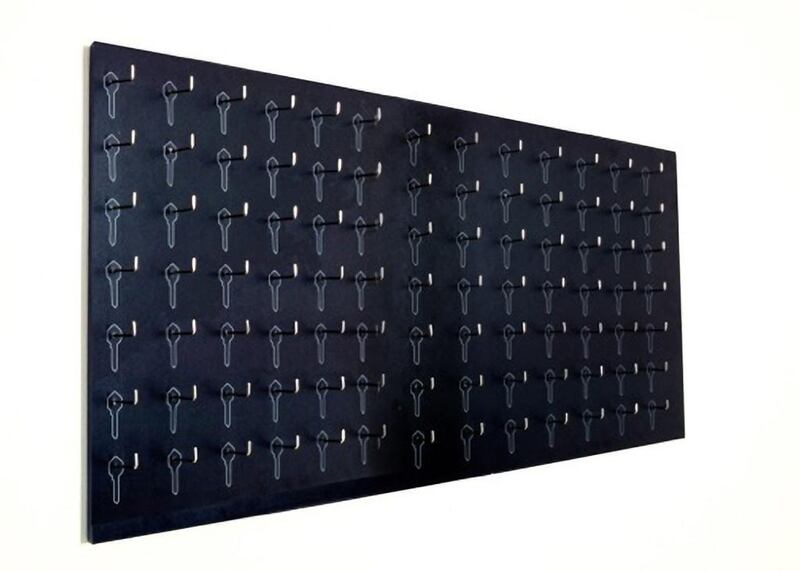

Clevers died in 2009, but an interview with him, conducted by Hassan Sharif in 1999, is included in the book and the exhibition includes his wood, linoleum and iron wire sculpture Spoon (2006), which was only recently rediscovered in The Flying House, the Al Quoz-based exhibition space established by Abdul-Raheem Sharif in 2007 that now doubles as Hassan Sharif's archive and the home of his estate.

With its emphasis on the interviews that were conducted in preparation for the exhibition, the text is as much a group portrait and an exercise in social history as it is in the history of art; and, Allison admits, one that reveals just how much research still needs to be done to fully understand any future narrative of the period.

“One of the things that we have tried to do is to remap the period before the community became known as the Flying House Group, because that group didn’t actually include many of the people who were involved earlier and were critical to the formation of the artistic scene here,” explains Kattan.

“Most of the members of the community are still very active and are quickly becoming much more famous internationally, but there are a few who have either passed away or have continued their careers abroad, so folding those people back into the history and reminding people that they were once a part of the community was also a motivation.”

Allison adds: “The whole premise for this community was that they were operating off-the-grid, in many ways, from any sort of mainstream arts infrastructure.

By encouraging her to continue with her research, Allison’s interviewees effectively reverted to a form of mutual support that they had previously used to sustain themselves during a period when Hassan Sharif’s house had formed their focal point and when the artist had acted variously as their tutor and a mentor, providing inspiration and criticism, encouragement and direction.

Each had tales to tell of his impact on their practise, which Allison has recorded, and which testify to the historical moment.

“Everyone is realising that there is a history to be written,” Allison says. “Each of us is doing our part, but I imagine that there will be a point when somebody actually comes back and looks at what we’re doing right now, goes back into the archives, looks at the original Arabic and does a lot more than somebody generating an exhibition can do.”

For Allison, Kattan and Edris, But We Cannot See Them is not only an opening gambit in the writing of that history but an attempt to map and understand the social conditions and intellectual milieu that gave rise to the art that was produced.

The fact that a cultural community emerged in the UAE at a time when there was little recognisable arts infrastructure not only stands as testament to the gravitational force exerted by Hassan Sharif’s charisma, talent and intellect, Allison says, but also to the important role that communities can play in fostering creativity.

“Why make art when it’s really hard? When people don’t appreciate it? When it doesn’t pay well unless you strike it big?” the curator asks.

“What motivates an artist beyond being discovered? The answer to that question, I find, is the communities that are formed by people who want to make art ... are driven by the idea that art is something that’s really worth doing. The end.”

“That’s a motivation that binds communities together and allows them to reinforce and support one another. Without it,” Allison says, “people can get really beaten down.”

• But We Cannot See Them: Tracing a UAE Art Community, 1988-2008, is being shown at NYUAD Art Gallery on the university’s Saadiyat campus from noon to 8pm, and runs until May 25. For further information, visit www.nyuad-artgallery.org.

Nick Leech is a feature writer at The National.