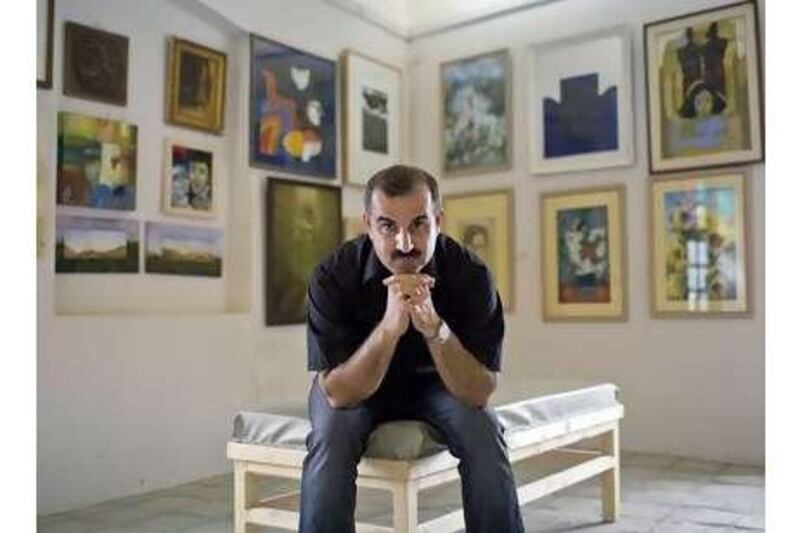

I was sitting directly across from Rostam Aghala, a sharp-looking Kurdish painter with a black moustache, when it hit me. This is the most negative man I have ever met. Throughout our interview, I had peppered him with questions that I thought might produce a good story: What is the art scene like here in this idyllic region of Iraq? Is it rising from the ashes? Suddenly vibrant? Political? With the expression of a doctor delivering a terminal prognosis, he began to respond: "It's too late for art in Kurdistan. People in other countries - art is very important to them. Here they don't care."

Surprisingly, Aghala is the proprietor of Zamwa, the premier gallery space in Sulaymaniyah, a Kurdish city of about 800,000. The space is located in a beautiful hidden courtyard accessible only from a side street inside a densely packed souq. The doorways of the house - owned by Hero Talabani, the wife of the president of Iraq and Zamwa's sole patron - are painted a bright turquoise, and a large, sunlit olive tree sticks out of the cobble stones. It could be a boutique gallery in Greece or Sicily, except for a single reminder of the region's history. One artist has taken an old rocket shell from the days when Saddam Hussein attacked nearby Halabja and made it look like green apples are pouring out onto the ground like a waterfall.

Disheartened a bit by Aghala's first response, I tried to ask about visitors - do they come? Are they locals? "No one comes to visit," he deadpanned. "Except for the odd journalist... But they don't like to interview me because I am so negative." I studiously wrote these answers down in my notebook, silently wondering why some interview subjects try so hard to kill your stories. But when I looked up, I saw a faint smile had formed on Aghala's face. So I decided to take us down a new path: Do they give you some kind of nickname around here because of your attitude?

"Yes!" he said, seemingly delighted with the question. "They call me Rostam Sheit." My translator turned to me and said: "It means crazy Rostam." "I see," I said, eyeing him. "And may I ask, are you happy to be an artist?" His smile grew as the translator asked him the question in Kurdish. "Absolutely not!" he said. "I don't want to be an artist - they don't have a good reputation. I wish I was wealthy and I had a hotel in the mountains for the tourists that come out here. Every time I have an art show, I regret it. Nobody buys anything."

Before I had a chance to laugh, he continued: "But art is my life. I love it so much, even if I hate it." And finally I felt I had managed to glimpse the heart of one of Kurdistan's greatest living painters. He is a walking, talking contradiction - both utterly miserable and doing the only thing he could ever do. Every aspect of his process is tortured. "I can't think when I paint, or when I do anything. If I do, it is always wrong."

He used to destroy most of his paintings, until one day he sold one for $4,000. "Ever since then, my wife does not let me throw away the bad paintings. They sell for more than my good ones." Recently she has started giving Aghala tips to make him more successful: "She wants me to paint people smiling and women with their clothes on." But he hasn't taken the advice. His work is mysterious and folksy. One of his paintings shows a pensive, young Kurdish woman in front of a house with pomegranates and poppy flowers. Her expression conveys a melancholy spectrum - her world seems closed despite the fact that she is sitting in an open field; she is in love but paralysed.

Another painting at first appears to be a simple illustration of a rug, but a closer look reveals an entire city depicted in the patterns of the weave. "It is a kind of map," he said, pointing his finger at the designs. "Here are side streets, houses, and here, people." Sitting with Aghala, drinking sweet tea from small glass cups, I get the impression that if I were to come back in 10 years, he would still be at Zamwa, a reluctant artist shifting paintings around in a museum with few visitors and little interest from the million-dollar art scenes of Paris and New York.

"I try not to think about it," he said. "Really, I wish I was something else. But at night, I stay up and all I can do is paint."

bhope@thenational.ae