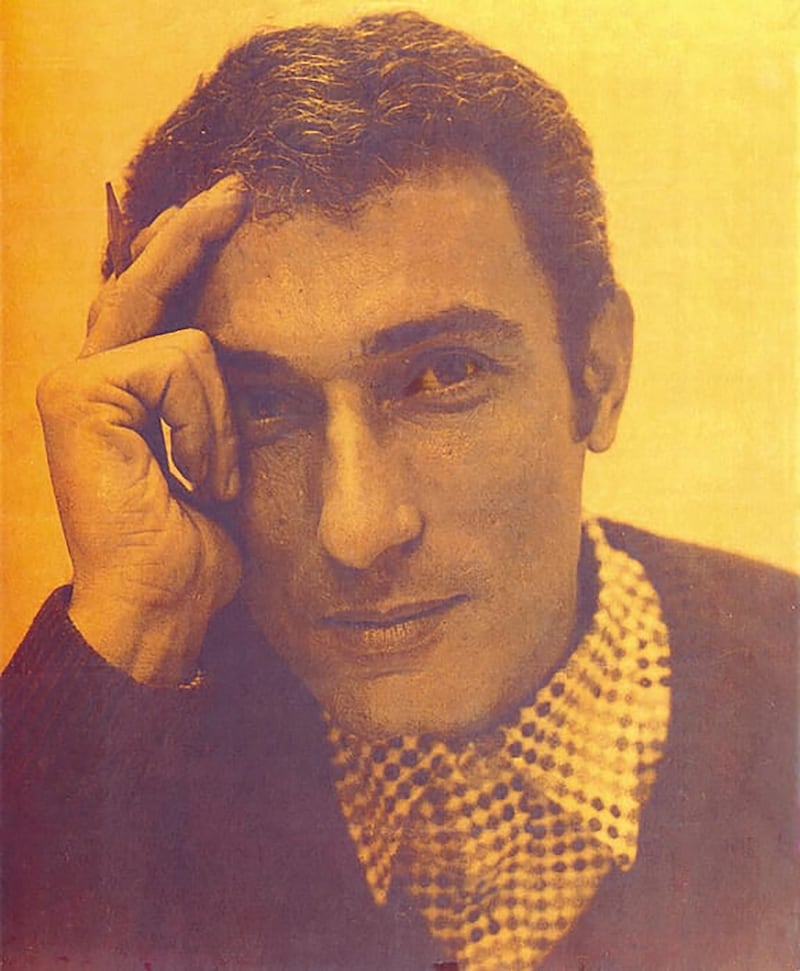

On July 22 1987, Palestinian political cartoonist Naji Al Ali was shot in the neck outside the London offices of Kuwaiti newspaper Al-Qabas. He died five weeks later, at the age of 49, in Charing Cross Hospital. Despite the Metropolitan Police reopening the case last year, no one has ever been convicted of his murder. "My father knew the path he was taking might lead to his death," Al Ali's eldest son, Khalid, revealed in a recent interview. "But he was very hard to scare off."

This refusal to be silenced made him one of the most important political cartoonists ever to have emerged from the Middle East. In more than 40,000 cartoons, Al Ali, who was damning of both the Israeli and the Arab regimes, never once compromised his views. He refused to endorse any agreement that did not include the Palestinian right to all of historic Palestine. But he could be as critical of what he perceived as Palestinian Liberation Organisation (PLO) hypocrisy as he was of Israeli brutality.

In the weeks prior to his murder, it is alleged that Al Ali received a threatening phone call from a senior member of the PLO, in which he was told: "You must correct your attitude." The cartoonist promptly published an illustration attacking PLO leader Yasser Arafat. "He has this incredible crossover appeal because he was really an independent thinker and a staunch critic of all authority," Jonathan Guyer, an expert on Arab comics told The New York Times last year.

Born in 1938 in Galilee, Al Ali was forced to move with his family to a refugee camp in southern Lebanon in 1948 as a result of the Naqba. This, inevitably, had a profound effect on the cartoonist. “To the end of his life, he wanted to go back to his village, he wanted to go back to Palestine,” Khalid said.

As a young man, Al Ali was detained a number of times by the Lebanese intelligence service, which was cracking down on political activity in the Palestinian refugee camps. “I drew on the prison walls,” he said. Al Ali later emigrated to the Gulf, where he worked as a mechanic, before returning to Lebanon to take up a place at art school.

Soon after, he began working as a journalist in Kuwait, but his talent for drawing cartoons was quickly recognised and, from 1963 until his death, his work was published in newspapers across the Middle East.

His most famous creation was Handala, a young boy depicted with his hands clasped behind his back, who appears in many of his cartoons. Handala’s back is always turned away from the viewer, according to Al Ali, “in protest of the world’s complicity in the occupation of Palestine”.

The little boy was a symbol of Palestinian defiance, but he also served as the conscience of Al Ali’s cartoons. “Handala has promised the people that he will remain true to himself,” he said. “He is barefooted like the refugee camp children, and he is an icon that protects me from making mistakes.”

Thirty-one years on from Al Ali’s murder and it seems that the police are no closer to finding his killer. The legacy of his cartoons remains potent, however, his anger at the treatment of the Palestinian people as relevant now as it ever has been. “He wanted to make you think,” Khalid said. “What he had to say, he said it. What he had to draw, he drew it.”

___________________

Read more:

Palestinian arts and crafts that tell a story of the ages

Ahed Tamimi’s face has launched a million clicks: the hefty price of expression in Palestine

First Palestinian art museum in US opens its doors

___________________