David Gargill travels to Anchorage to examine the roots of Sarah Palin's spectacular and sudden ascent from the depths of obscurity to the heat of the national spotlight.

By mid-September the freakishly robust growing season in the Matanuska-Sustina Valley was winding down. Home to some of the world's deepest topsoil, and blessed with 20 hours of sunshine on long summer days, the Valley is renowned for the oddities of scale that sprout from its earth. 90-pound cabbages are commonplace at the State Fair in Palmer, a sleepy agrarian hamlet at the foot of Pioneer Peak. During America's Great Depression, Franklin Delano Roosevelt uprooted struggling Midwestern farmers and transplanted them atop the rich soil of the valley, hoping to engender civilisation in a landscape both lush and forbidding.

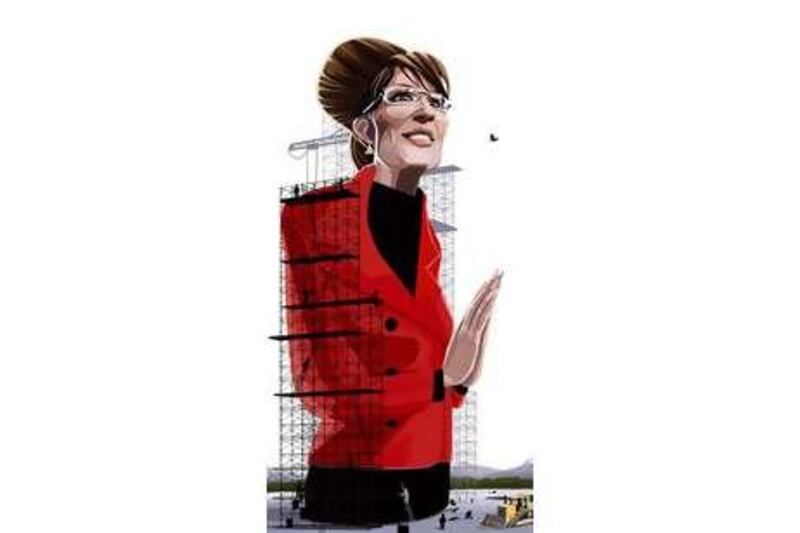

These days the Mat-Su is also fertile terrain for the cultivation of myths, and ever since John McCain selected Sarah Palin as his running mate on August 29th, a great many concerning the Wasilla native have blossomed here. Palin stormed onto the national scene like few American politicians before her, a self-professed "hockey mom" who single-handedly saved the Republican convention amid torrents of press attention and a swooning embrace from movement conservatives. Her debut took the nation's eye off the storms battering its Gulf Coast, reenergised a Republican base leery of the Senate's Maverick, and catapulted the obscure former mayor and city councilwoman to international rock-star status as fast as bloggers could post.

But ignorance is bliss, and as this unknown was cast in greater relief by each datelined detail, the bloom wore off the rose - if only by a few points - and suddenly, Palin's place on the ticket posed more questions for the McCain camp than it answered. The national and international media departed en masse for points north to vet the Vice Presidential candidate, perhaps for the first time. Her broad, smiling face and signature upsweep graced every glossy in the country while her record in Alaska was ruthlessly dissected in the broadsheets.

The slow drip of unflattering news from the north and a handful of disastrous media appearances sent Palin's poll numbers tumbling, but she continued to attract record crowds of fervent admirers to the previously somnambulant McCain roadshow. But for a candidate thrust into stardom fuelled by her folksy authenticity, the real Sarah Palin remained an enigma, cloaked in the protective embrace of a campaign determined to shield her from scrutiny. Was she a moral paragon ready to "clean up Washington" - or an abuser of power who conducted state business on private e-mail accounts to avoid oversight and used her office to settle family vendettas, dismissing Alaska's respected Public Safety Commissioner because he refused to fire her sister's ex-husband? Was she a woman of faith and family to whom the majority of Americans could relate - or an End Times-awaiting creationist book-banner? The archetype of Alaska's fabled frontier spirit - or a pork-barrel grifter in the mould of Alaska pols like Congressman Don Young and Senator Ted Stevens, both under investigation for corruption? The truth was protean and elusive, lost somewhere in the great divide that separates Alaska from what its residents still call "outside" - the rest of the United States. When I set out for the Valley a few weeks ago, Palin had just stumbled through an interview with ABC's Charles Gibson - but her drawing power endured, as 10 million people tuned in. The big papers unloaded their lengthy reports from Wasilla and Anchorage ("Once Elected, Palin Hired Friends and Lashed Foes" was The New York Times headline) but the base remained besotted. In the last week, however, a stream of high-profile conservative apostates have soured on Palin, the last straw apparently a disastrous interview with Katie Couric that stretched over three nights of national news like a slow-motion car crash. To David Frum, the former Bush speechwriter who coined the phrase "Axis of Evil", Palin had "proven pretty thoroughly... that she is not up to the job", while another prominent right-wing columnist suggested Palin withdraw herself now to save McCain's chances. It was a startlingly fast journey from saviour to scourge - with the final chapter still unwritten: will Palin's inexperience sandbag McCain? Or will her ineffable appeal to hard-working "regular folks" save the day? In Alaska, people are uneasy about their state's new status as a hub of partisan chicanery and intrigue, and ambivalent at best about all this attention from the lower 48. They now have a horse in this race and mere loyalty would usually lead most folks to stand and cheer, or simply clam up and ride the bandwagon home for The Big Win. But in what they like to call "the world's biggest small town", anyone who wants to know the dirt on Sarah Palin can find it. Kinship has its limits, and for Palin, who has thrown more than her share of sharp elbows in state politics, negative stories heading downstream - from sources in both political parties - now threatened the seaworthiness of McCain's vessel. The only question remaining was whether the flow could be staunched before the old Navy man at the helm was forced to toss her into the drink.

When I arrived the Governor was the literal talk of every town, and every TV set - muted in a briny smoke-filled bar, or presiding over a disappointing hotel continental breakfast - was tuned to some conduit offering news of her exploits. She was the subject or subtext of every conversation, and since the majority of Alaskans knew her personally - or felt they did (a testimony to her considerable political skills) - facts and opinions regarding her past were being everywhere disseminated, rarely without some hack reporter within earshot to absorb them. These notebook-wielding Huns had so tenderised the populace that all but the most hostile natives by now proved pliant and yielding, and so I sought out a few people who witnessed Palin's rise first hand and a few who admired it from afar in an attempt to understand her unlikely ascent to power, her troubles in office, and the irresistible sway she still seemed to have, a magnetic hold on voters that even some of her estranged allies could neither shake nor fathom. I couldn't see out the window of the aeroplane that brought me into Anchorage, and so it was in the queue for a rental car that I got my first impression. The panorama looked like a blast site, as if the range of jagged brown seismic cones had not been hewn by the implacable advance of glaciers or tectonic pressure, but by a sudden violence far beyond the human scale. On the majestic drive north from Anchorage to the Mat-Su, the frontage roads fall away with the brief wooded and wood-sided suburbias of Eagle River and Chugiak, and soon the vast tidal plane of the Knik Arm presents itself, peeling off into the western distance. The lowlands have gone maize and duelling shades of green in an early autumn flourish. Past the Knik, termination dust - the lovely Alaskan term for the first light touches of snow that "terminate" the summer - painted the massifs to an even level across the eastern side of the Valley. The sight of things so huge soaring so high filled me with a sense of impending, of peril and awe. Their astounding permanence, the impossible finality and atemporal aspect of them struck a near-spiritual chord. Eternity felt undeniable in a place like this. And Jalmer Kerttula had been active in Valley politics for about that long, witness to a (relatively) brief but eventful epoch. He arrived in 1935, 14 years before statehood, and served as a legislator for over thirty years, presiding over the house and the senate - a living reminder of the hardscrabble men and women whose tenacity (with a generous assist from Washington's largesse) made Alaska. "My father had been here before," Kerttula told me as we sat in his living room, "he was first mate on a ship that got iced in out of Point Clarence in 1921." Kerttula, known to all as Jay, left the legislature in 1994, after being ousted by Lyda Green, the current senate president. He's dressed in old grey flannels, a striped button-down shirt and broad suspenders, his jawline lost behind a full-on beard in the style of Reagan's surgeon general, C Everett Koop. Jay, the first Jalmer I've ever met, seems to have less nostalgia for the years he spent in power than for the rough place where he came of age. "The federal government purchased all the homesteads in the area and then sold them at thirty years and three per cent," he tells me, "deep soil but windy." I crack a smile because I'm reminded of a piece of local wit I've picked up, "Wasilla sucks but Palmer blows," but it's not the moment for me to share it. "Wasilla was the inheritor of a tiny community at Knik. That was where Joe Palmer brought his three mast schooner in, and he had a drugstore, a hotel and several things. Slowly the railway came in on the way to the mines and Wasilla essentially had an old sales & service store, Hearning's, a grocery, a hardware store and a hotel. Down by the lake you had some other properties, some whorehouses and stuff, but you don't mention that. Years later, a post office." "But what's Wasilla?" Kerttula asked rhetorically, tracing what registers as the arc of the Valley's squandered promise, "It's a series of pretty good sized national stores, Wal-Mart, Target, so on, then there's housing around the edges, helter-skelter. It's an oddity. It's not like a normal city with one street after another, but you've been there, so you know what it is. I don't see it as a good training ground for anybody." I had been to Wasilla. It didn't come highly recommended, and for the most part the town failed to exceed expectation. The New York Times columnist Maureen Dowd dubbed the town "a soulless strip mall," but that seemed a facile dismissal of this grim warren of sanitised neon storefronts glinting in the utter dark, nondescript clutches of buildings as disposable as the items dispensed through their doors and drive-through windows, dwarfed by the snow-crowned mountain peaks that disapprovingly framed the distance. The trivial held in the palm of the profound. Inside the local Taco Bell, I slunk back to my seat with my trove of novelty food and sat by the window. Mall-dwelling teenagers laughed, shouted and generally had a tough time sitting still, while joylessly attired farmers ate in silence, soundlessly grinding their fair share of boiled ground beef and milled corn with their jawbone beards. (This C Everett Koop look was apparently hanging on strong with the Valley's gentlemen farmers). Perhaps kids got married a little earlier up here; maybe gun ownership was less dangerous than going without; but those differences aside, the view was indistinguishable from that of any Taco Bell in Ohio or Pennsylvania. At times Alaska seems almost Soviet - sloughing off rugged individualism for annual dividend checks from the permanent fund - but it is indelibly American, and the McCain camp is counting on the fact that Palin could mount a strong showing in towns like Wasilla in the lower 48. From where I sat, they were legion.

When I walked into Lisa Catlett's house, out near mile marker seven on the Wasilla Fishhook Road, she'd seemed busier than I'd ever been in my ever-loving life. Her four children swarmed around her and the house, three boys and a girl ranging in age from eight to two. She was dealing with the thirty-odd salmon fillets she'd just brought in from the smokehouse for canning and vacuum sealing. On top of that there was the unwanted journalist who'd insinuated himself into spending the afternoon with her and her family to see how real Valley people got on. At first I walked up to the wrong door, past several four-wheel drive vehicles and drooling hounds. After introducing myself to the man of the house, I asked if he was Rob. He said no. I asked for Lisa. He asked who I was, warily: "You trying to collect a debt?" We sorted it out but the message was clear: people look out for their own here. The Catlett clan had a serious spread. A creek ran from the road up the left edge of the property, past a trampoline, back into the forest. The lane led toward a large clearing hewn out of the cottonwood, birch, aspen, brambles and underbrush, where there stood a matching house and guesthouse, with dark wood siding and green roofs. The smokehouse, with huge metal doors borrowed from a meat locker, stood between them. Outbuildings were in abundance: tree houses, a skate shack, chicken coops. Lisa spent the summer between high school and college here, "just to get an Alaska experience," and after meeting and marrying her husband Rob, an electrician, in the lower 48, returned to Alaska to raise a family. The children are all home schooled. "I went to a great books college," Lisa says, as her kids port ducks around the property, arguing about their names, "and that really changed my perspective on what I wanted my kids to learn. I want them to read all the great books and speak a couple of languages, and I thought they probably wouldn't get that in the public schools." Rob woke her at 6am on August 29th to tell her the news about Sarah Palin. "I was like, no way! That's so awesome!" Lisa, neither partisan nor intensely engaged with politics, had no doubts about the scope of Palin's personal appeal. She had once voted for the famously unpopular former governor, Frank Murkowski - who Palin later unseated - and almost instantly regretted it. "I'm tired of the good old boys - they're so removed from us. And that's what I think Sarah's appeal is, she's like us. She does get her own caribou, make moose burger, that kind of stuff, that seems Alaskan. I don't need somebody to cook for me. I have to haul my own wood inside when it's cold." "When Obama came out I made it a point to watch him," she continued. "He was on some talk show telling some story about how he didn't like Grey Poupon, he liked mustard, and the whole thing seemed like a charade, you know? I thought even this attempt to be an everyman was fake, you're a fake in a different way but you're still a fake and I don't buy it and I love Sarah Palin! I just think she'll tell it like it is and doesn't care if it upsets people." I ask Lisa what she makes of the stories detailing Palin's spotted record as a reformer in Alaska, but she's undeterred. "I don't know," she says, "that may be true. Maybe I'm jaded but I think all politicians are politicians, I just think it's different degrees. I still like Sarah, I think maybe she's the least tainted that I've ever seen."

Andrée McLeod is shouting into the phone from a desk set up in her bedroom as I wait for her at a kitchen table annexed by stacks of paper. "She's only powerful if you think she is! This right here, if it turns out to be true, is a bunch of bull****!" It is because of McLeod, a lovably obstreperous woman of Armenian descent somewhere in her fifties, that the world knows of Governor Palin's preference for Yahoo over .gov - one of the little details from Alaska that suggest uncomfortable parallels between the modus operandi of the Palin State House and the Bush White House, which also liked to transact government business on private e-mail accounts. The stacks covering the table are the fruits of McLeod's request for e-mails and phone calls between Palin and two aides, whom McLeod suspected of working in concert to oust the Alaska Republican Party chair, Randy Ruedrich - a violation of the state executive ethics code, which forbids conducting party business on state time. It might seem a venial sin - but it was also precisely the accusation Palin had earlier wielded to eject Ruedrich from the Alaska Oil and Gas Conservation Commission- with the help of Andree McLeod herself. McLeod emigrated from Beirut with her family in 1963, and moved to Alaska from Long Island thirty years ago. She was apolitical until 1995, when she spied an opportunity to earn money for grad school by operating a falafel cart in Anchorage. The town fathers squashed her plans, declaring fried chickpeas "potentially hazardous." She took the fight to city hall, wound up running for mayor, and her local state house seat twice, losing the last time in a tight race that required a recount. McLeod told me that she'd met Palin shortly after her own failed state house bid in 2002. They'd stuck up an unlikely friendship, the home-grown beauty queen and the cerebral but scrappy and energetic import. Palin complained to McLeod about Ruedrich's penchant for doing party work from his office at the AOGCC, where Palin also served - appointed by Murkowski after her losing bid for Lt. Governor marked her as a "comer" in the state party. McLeod got tired of Sarah's ceaseless complaints and told her to do something about it already. "She didn't know how to go about it," McLeod says. "I would guide. So that reporters would ask her, but there was a role I played in the background, making sure all the information was correct. But she did the exact same thing she accused Randy of doing. Had I known that I wouldn't have given her the time of day." The takedown of Randy Ruedrich was Palin's first public scalping (of a fellow Republican, no less) and it helped cast her as a dogged reformer. "It's true, Andrée's almost responsible for creating Sarah Palin," Rick Rydell, an Anchorage talk radio host and 2004 Alaska Republican Man of the Year, tells me over sushi a few days later. Rydell has just finished his show, which airs weekdays from six to nine in the morning. His Harley is parked out front and we're sampling some hijiki and gyoza, talking about the Palinistas - his disparaging moniker for those still "drinking the kool-aid." He's been in the business twenty-seven years, first in Juneau, then Portland, getting as far east as Cleveland before returning to Alaska eighteen years ago. "Being here the day Sarah was announced as McCain's VP pick," he recalled as he tossed slabs of raw fish under his thick handlebar moustache, "was like being at the centre of a nuclear explosion, just like all eyes were turning and looking right where you're sitting." But McCain's pick didn't impress him. "I said this on the air the first day: this looks like a Hail Mary pass downfield into heavy coverage. And I still think it holds pretty true." Rydell had been a friend and confidant of Palin's over the years; she and her husband Todd - the self-styled "First Dude" - had even attended his wedding. Yet Rydell was not the only prominent Alaska Republican to break with the Governor. She still has a glut of fans and political allies in the state, but does appear to have alienated an alarming number of those who have been allowed behind the curtain - among whom it is said that even in Palin's crusades for ethics, ambition has often trumped principle.

Laura Chase has a message for the world: "There isn't a day that goes by that I don't wish I hadn't done my job so damned effectively." The job in question was managing Palin's successful campaign for mayor of Wasilla in 1996. Palin ousted three-term incumbent John Stein in a rough campaign; she secured the endorsement of the National Rifle Association and injected hot-button "wedge" issues like abortion into the race for what had previously been a non-partisan office, affixing to Stein the label Palin would later use so effectively statewide to bring down entrenched Republican pols - "Good Old Boy".

Chase was born in Palo Alto and moved to Alaska before statehood. She, like Palin, holds a degree in communications from the University of Idaho. "She was viewed very positively," Chase said, recalling Palin's arrival on the Wasilla City Council. "First of all, she's a really attractive young lady, and to get involved on the council, which was full of a bunch of old folks, was a real shake up."

Palin later asked Chase to run her campaign for mayor, and after overcoming reservations about unseating "a good man" like Stein, she accepted. "She said that if she won she would hire me as the city administrator," confides Chase, still incredulous, "and that the two of us would provide leadership for Wasilla. The second she won, she didn't even remember who I was." The fact that she remains crushed is clear.

"I'm still proud of Sarah," Chase confessed to The New York Times, "but she scares the bejeebers out of me." When I asked her to elaborate, she mentioned Palin's effort to remove books from the public library, which Chase claims she witnessed first hand. "There's no place in the world," Chase says today, "for people who don't believe what she believes."

There was a knock at the door - and a reporter from American Media - publishers of quality supermarket checkout titles like Star and the National Enquirer - came in to take Chase's picture. The reporter asked Chase if "she still had the letter," but Chase told him it had been shredded. He quickly took his leave, and it was just us and the awkward silence.

After a few moments I asked about the mysterious letter. "Oh," Chase sighed, "a week after she won the mayor's job she dropped by my house and handed me a check for $1,000" - intended to compensate for the job that had failed to materialise. "I tore it up, handed it back, and told her she was lucky that Todd put up with her. A few days later I received a three-page hand written letter saying, 'How dare you? You don't know anything about mine and Todd's relationship."

Chase tells me she shredded the letter because "If I kept it I'd never be able to let it go. It's kind of a love-hate thing, you know?" And I did know, because over the course of the hour I'd spent there, I was shown at least two hulking Palin scrapbooks that were still very much intact. If anything, I suspected, the letter was purged because it severed once and for all her connection to the warm fuzzy she clearly derived from the news clippings and other Palin campaign kitsch she so obviously prized. We found ourselves in silence again.

"I just wish I didn't feel this way," she told me, her oval face more dour now, "because I am so proud of her."

I asked her about this pride - since she had evidently soured on Palin - and suggested it might relate to the wave of "local girl done good" and "she's one of us" feelings washing over Alaska.

"She's nothing like us!" she stammered, "she doesn't know what it's like to not be able to pay the bills, to not be able to get credit cards or health insurance for the kids. Not everyone has what they have; that image is a lie. And it's not that she's like us. We'd like to believe that. People are living vicariously through her. They feel they're missing something in life. But she has that way where she can impact someone in that manner; its like you feel you're living that life, and that's why she can say 'Oh, I'm just one of them,' because we're desperately trying to live vicariously through her energetic and determined lifestyle. Maybe that's why I'm so damned proud of her - I'm doing it too."

As Palin prepared to meet Joe Biden in this week's vice presidential debate - and Republican cadres worried publicly about a repeat of Palin's recent public missteps - I wondered if Palin's ineffable appeal insulated her against even the worst performance she could deliver. Consider that Laura Chase and Andrée McLeod, former intimates of Palin turned vocal critics, both offered their services to the Governor after their disenchantment with her. It seemed as though she had kindled a faith - perhaps borne of idealism - that exceeded anything they had known before or since, and a certain nostalgia for that earlier moment posed a constant temptation to return to the Palin camp.

Palin has a way of transcending the obstacles that come her way, gently bypassing possible scandals with apparent ease and little damage to her sky-high approval ratings in Alaska. "Troopergate" - with its allegations that Palin fired Public Safety Commissioner Walt Monegan when he failed to dismiss the Governor's ex-brother-in-law, a state trooper - would likely have felled a lesser personality, but Palin seems to have evaded censure, particularly now that the McCain campaign has devoted its substantial resources to quashing the investigation.

State Senate President Lyda Green told me she knows full well the "Troopergate" allegations were substantial, because she knew the trooper in question, Mike Wooten. When he told her details from his confidential personnel file were being used against him by the lawyer for his ex-wife, Palin's sister, Green says she contacted a friend at the appropriate state agency. "I made inquiries," she said, "and the guy who I talked to happens to be a friend, and he said, yeah, we're having a little problem with that.'"

But that inquiry has been stalled by a Republican lawsuit and Palin has begun to take on a Teflon sheen to which nothing can stick. Before I left Alaska, I learnt that the local papers had indeed reported on the substance of McLeod's allegations against Palin - that she committed the same offences for which she persecuted Randy Ruedrich - but Palin waved them away with a brief response: "For any mistakes like that, that were made, I apologise."

None of this stopped Palin from coasting into the Governor's mansion, and her approval rating - even with the additional pressure of national scrutiny - is still near a robust 70 per cent.

"It's almost to the point now where people don't care about her politics," Democratic State Sen. Bill Wielechowski admitted, "this is such a small state that it's like a family, and you want to see family members succeed. People are just so proud of her and maybe she had to throw a few people under the bus, but she's still ours and she's making us proud."

David Gargill's work has appeared in Harper's, GQ, and several other publications. He last wrote for The Review on the artist Wafaa Bilal.