The story of Ziggy Stardust, David Bowie's most enduring alter-ego, is a cautionary tale for any aspiring Martian rocker. It goes something like this: Earth society has received a prophecy of the coming apocalypse - we have, in fact, only five years left. Still, there remains a distant hope of salvation offered by recently received extraterrestrial communications. Into this environment, an alien rock star falls to Earth, where he projects all that is most vibrant about music and art, and is accorded messiah-like status. Unfortunately, he has his head turned by terrestrial pleasures - and ultimately commits suicide.

Or so the story goes. However, it now appears that Ziggy didn't commit suicide at all, but was assassinated by his creator. Ziggy had everything to live for: a cool band, huge success, and a series of touring engagements. But on July 3, 1973, on stage at London's Hammersmith Odeon, David Bowie, in his full Ziggy regalia, announced Ziggy's death: "This show will stay longest in our memories," he told the assembled crowd, "Not only because it's the last show of the tour, but because it's the last show we'll ever do."

What followed were scenes of confusion, and in some cases, anguish. Some audience members wept. Bowie's band, who hadn't been told about any of this, were furious. The music weekly Record Mirror published a story that week saying that David Bowie had quit touring altogether. No one seemed certain what was going on: had Bowie given up? Was Ziggy real? Was Bowie an alien?

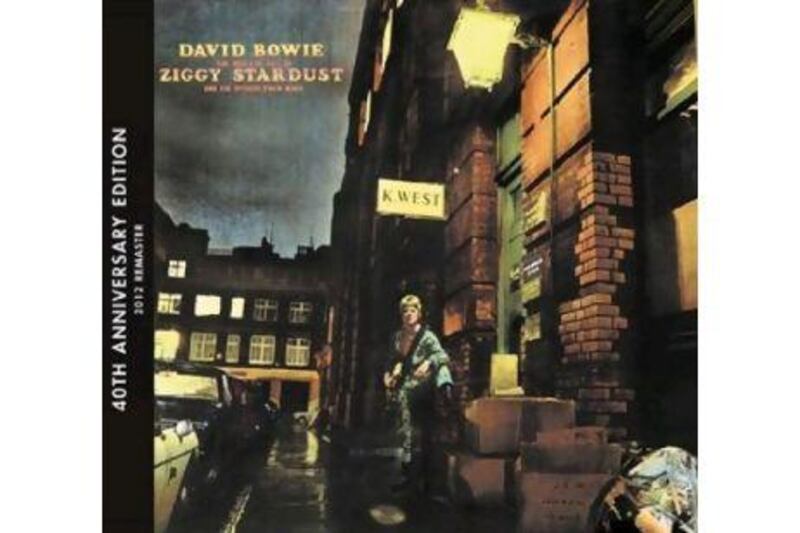

It's fair to say on that day in 1973, David Bowie would have been unable to give you a definitive answer about what was going on - but he was undoubtedly delighting in the confusion. After spending eight years in the music business with limited success, the titular hero of his 1972 album The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars had captured the imagination of teenagers in Britain and America. But rather than milk the adulation, instead Bowie decided to cut it short: seize the initiative and kill his creation off.

In the years immediately prior to 1972, David Bowie was probably best known as a man of considerable talent (his 1969 single Space Oddity had shown his knack for eccentric, topical composition) but one lacking in direction. Since Space Oddity in fact it occasionally seemed as if he may have, like his creation Major Tom, drifted out of orbit altogether. Since the single, he had made another album, The Man Who Sold The World, which his record company had released in the US, but didn't seem particularly bothered about releasing in his own country.

His folksy, charming Hunky Dory album from 1971 had yielded Life On Mars? - a widescreen hit single in which the parlous state of the world caused Bowie to turn his thoughts to the possibility of more civilised life on other planets - but he was toying with any number of different directions, committed to none completely. He released records under his own name, but also acted as writer-producer for pet projects such as Arnold Corns (an outfit featuring his stylist, Freddy Buretti) and later for Mott The Hoople, for whom he wrote All The Young Dudes - a song about youths as harbingers of a coming apocalypse.

Many of these ebbing moods and diverse roles he chose to channel into his next batch of songs. Recorded almost immediately after it, and with the same band as Hunky Dory, the songs that became the Ziggy Stardust album were recorded with a simple brief (as producer Ken Scott recently remembered it, Bowie simply said they would be "more rock 'n' roll"). Nonetheless with songs like the great Moonage Daydream it became a collection that would help to identify Bowie not only as the embodiment, in all its many meanings (outsider; actually from another planet), of "the alien" in popular music, but also as its principal commentator on celebrity. Outsiders of a slightly more ordinary kind in Bowie's audience could suddenly believe themselves so empowered, even similarly attractive - perhaps the most significant social bequest of what became "glam rock". Glitter-covered, they flocked to him.

So who was the inspiration for Ziggy and his boom-and-bust trajectory? We can't know for sure, but Bowie was certainly drawn to the story of the British singer Vince Taylor. Once a pioneering rocker (most notably with the single Brand New Cadillac, later covered by the Clash) Taylor's mental health issues had led him to believe himself, by the time he met Bowie in the late 1960s, to be an alien messiah. There were other possible inspirations, too. Jimi Hendrix (a guitarist who, like Ziggy, "played it left hand" and died young). The troubled Pink Floyd singer Syd Barrett (the name Arnold Corns was a homage to the Pink Floyd single Arnold Layne). Even Marc Bolan (when he played Lady Stardust live, Bowie projected an image of Bolan behind him).

Really, though, Ziggy was Bowie's show. Since the start of his career, Bowie had struggled to find traditional identities to inhabit, but none of them had fitted him particularly well. Sax-playing frontman of rhythm 'n' blues combo. Exaggeratedly English, almost vaudevillian pop star (his 1967 debut album). Long-haired acoustic folkie. Now, with a spiky haircut and a set of extraordinary new clothes, Bowie became his new creation. Ziggy provided Bowie with an artistic alibi: with the character in tow, his messianic posturing and vaguely outrageous homoerotic stagecraft was entirely defensible. He was, after all, playing a role.

As Bowie recalled it, however, the boundary between fiction and reality quickly became blurred. On Live Santa Monica '72, recorded at a US show four months after the Ziggy album was released, Bowie does more than inhabit the role. As he said of the performance in 2008: "I'm so into it, it's no longer an act. I am Ziggy."

Now, we know what he means, but in 1971-72, Ziggy Stardust was just an interesting name, which anchored a set of very good songs. "Concept" is far too strong a definition of The Rise And Fall Of Ziggy Stardust. Instead, the album sketches an apocalyptic scene and places Ziggy within it, to reflect the madness around him. Even 40 years on, it rushes at you with one strong image (from Five Years: a cop kneeling at the feet of a priest), one strong riff (like that of Hang on to Yourself) after another. The music is primal; the ideas sophisticated.

And even in the digital age, it's a record with two sides. Side one, opening with Five Years, in which Earth is told of its impending apocalypse, continuing through Moonage Daydream and the hit single Starman, to the self-explanatory cover of It Ain't Easy sets the terrible scene. Side two, meanwhile, gives us Ziggy's brief life seen from multiple angles, the most persuasive being Ziggy Stardust, Suffragette City (another song offered to Mott The Hoople, but turned down) and the concluding Rock 'n' Roll Suicide. It's a kind of rock 'n' roll montage, its impressions ultimately more important than its making complete sense, the rawness of the sound harking back to the 1950s and the dawn of rock 'n' roll, and forward to the coming sound of youth.

As this anniversary reissue (brightly remastered by Ray Staff from Air Studios) makes abundantly clear, this is not one of those periods in an artist's career that offers up an abundance of unused or alternate tracks. Instead, there are just two cast-offs from the finished album here (Velvet Goldmine and Sweet Head).

In the next few years, Ziggy's mixture of raw rock, androgynous sexuality and self-invention would supply some of the building blocks of punk rock. They would also, of course, prove hugely important for Bowie himself. Having successfully inhabited a musical persona once, the way was clear for him to do so again and again. All that remained to be done was to find a way of disposing of the bodies.

John Robinson is associate editor of Uncut and the Guardian Guide's rock critic. He lives in London.