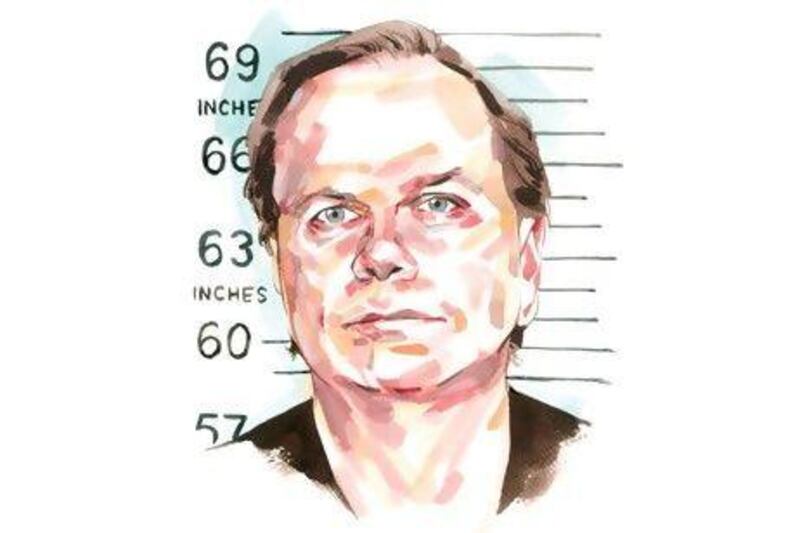

The man who murdered The Beatles's frontman in 1980 has voiced regret about his actions for decades. This week a parole board is again weighing whether granting him freedom would only "bring back the nightmare".

It became a day burnt into the minds of a generation. On December 8, 1980, the former Beatle John Lennon was returning from a recording session to the Dakota apartment building in New York that he shared with Yoko Ono and young son Sean. Out of the darkness, Mark Chapman fired four bullets into Lennon's back and left shoulder. Twenty minutes later, one of the most popular and talented musicians of all time was dead. Chapman, meanwhile, calmly read from his copy of The Catcher In The Rye at the scene, until the police arrived to arrest him.

If it seems like a long time ago, it is. Long enough, in fact, for Chapman not only to have reached the point in his 20 years-to-life sentence where he can apply for parole every two years, but to have done so six times. This week he was again before a parole board, hoping that his release will be palatable enough for the officials at his maximum security prison in Alden, New York. The decision rests with the parole board.

It's tempting to suggest that if Chapman hadn't shot and killed such a high-profile personality, he may well have been set free by now. After all, at his last parole hearing in 2010 he couldn't have been more penitent: "I wasn't thinking clearly," he stated. "I made a horrible decision to end another human being's life, for reasons of selfishness. I felt that by killing John Lennon I would become somebody and instead of that I became a murderer, and murderers are not somebodies."

Yoko Ono continues to campaign for his continued incarceration, believing that Chapman would be a risk to her family. Now 57, it's more likely Chapman would be at risk - from the media, from crazed fans bent on revenge, even from himself.

What's not in doubt is that Chapman bore all the traits of a killer saddled with a problematic past. Born on May 10, 1955, in Fort Worth, Texas, he certainly saw his childhood as troubled, telling psychologist Lee Salk after the murder that his father "never showed me love in any way ... I don't think I ever hugged him." Even his mother admitted in 1987 that she was "never like a mother with Mark - more like his best friend".

Given he saw his home life as so dysfunctional (although his mother maintained it was "pretty normal") it perhaps wasn't surprising that Chapman eventually turned to drugs at high school in Georgia. When he was interviewed by the psychological expert for the defence, Milton Kline, Chapman revealed he felt like a misfit at school, and began to fantasise about a world in which he was a hero king, "in the paper every day, and I was on TV, and I was important".

Worrying signs, but was he trying to explain away his appalling actions as an adult by finding a reason for them in childhood? It was difficult to tell; his mother had certainly been troubled by what she called his seemingly overnight conversion to drug use in 1969. And yet there was something telling in her interview with People magazine in 1987, when she admitted: "we had never leaned on him. He stopped going to school, and I just let him go".

By the early 1970s, however, he found a crutch in Christianity, working in a YMCA summer camp for children. One of Chapman's young charges, Cindy Simpson, would later say he "was about the best friend I had when I was growing up, and he was the nicest person I think I've ever known. I could see no wrong in that guy at all". His bosses were so impressed, he was nominated to go to Lebanon to help a charity mission, and he helped out at a resettlement camp for Vietnamese refugees in Arkansas.

Chapman, then, appeared to be thriving. But what happened next shaped the rest of his troubled life. His girlfriend began to notice "the big war going on inside him". He was brilliant with the refugee children, but began drinking and lost his virginity to a co-worker at the camp. The guilt consumed him. "Oh Jessica," he wrote. "I'm so sinful and filthy." Later, "I'm constantly struggling with my identity." Finally, devastatingly, "my ship is nearly sinking".

Enrolling at an evangelical Presbyterian college in late 1975 was an attempt to steady that ship, but by now Chapman was seriously depressed. Casting around for some focus, he began a job as a security guard. Perhaps the power and status such a role afforded Chapman was an attraction. It certainly didn't help. By 1977 he had made his first attempt to kill himself in Hawaii, but the hose attached to his car exhaust pipe melted and instead Chapman was admitted to hospital for clinical depression. "I was such a failure I even failed at killing myself," he once said.

For a while it actually seemed as if the Castle Memorial Hospital in Hawaii was genuinely the best place for him. On release, it hired Chapman as a part-time housekeeper. "He felt comfortable and unpressured," said Paul Tharp, the hospital's director of community relations. And after a trip around the world (which included Delhi and Beirut) he married his travel agent Gloria Abe in 1979 before getting a full-time job at the hospital as a printer.

The demons soon returned; the hospital couldn't promise Chapman promotion without a college education behind him, but he was, Tharp said, "afraid to go to school". He quit, returning to security work, convinced that his co-workers thought he was no good at it.

Most distressingly of all, just three months before he would kill John Lennon, he wrote a letter to a friend in which he noted: "I'm going nuts". He signed it "The Catcher In The Rye", the author J D Salinger's polemic against phoniness in society. The novel struck a chord with a man who, his wife later said, was furious that "Lennon would preach love and peace but yet have millions [of dollars]".

Still, though there were signs that Chapman was becoming increasingly obsessive, his ire wasn't initially directed exclusively at Lennon. There was a whole host of people who could have been caught in the crossfire that fateful December: everyone from Elizabeth Taylor to Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis was on his list. It was just that Lennon was more accessible, and Chapman felt most let down by a man whom he once saw as a hero, but who made him feel angry for singing that he didn't believe in God.

Yet even on the day itself, Chapman had not perhaps fully committed to his actions. After all, he'd actually spent most of it outside the Dakota and, earlier, had even asked Lennon to sign a copy of the Double Fantasy LP, which is chillingly captured on photograph.

As Chapman would later say: "I never wanted to hurt anybody. I have two parts in me. The big part is very kind; the children I worked with will tell you that. I have a small part in me that cannot understand the world and what goes on in it ... At that point my big part won and I wanted to go back to my hotel, but I couldn't. I waited until he came back. I did not want to kill anybody and I really don't know why I did it."

If only he had gone back. Like 9/11 or the assassination of John F Kennedy, everyone knows where they were when news came through that John Lennon had been murdered. In America, the sacrosanct Monday Night Football transmission was interrupted by the commentators saying: "Remember this is just a football game, no matter who wins or loses. An unspeakable tragedy confirmed to us in New York City". People gathered to light candles, cry and sing Beatles songs outside the Dakota. Later that month, a 10-minute silence worldwide led to every radio station in New York going off air. Desperate fans even committed suicide.

As for Chapman, he would plead guilty, eventually, to murder and began his minimum 20-year sentence in August 1981. He quickly went on a hunger strike, but otherwise settled into prison life with little fuss, spending most of his day outside his cell working on housekeeping and in the library. Interviews have been given, some of which Chapman has regretted (the photo shoot of him in the 1987 People magazine feature, in which he is holding an imaginary gun to his head and smiling is particularly repulsive), and some of which have been remarkably frank. "I thought by killing him, I would acquire his fame," he told ABC in 1992.

In fact, in his first parole application, the board actually criticised Chapman for giving interviews, suggesting he rather liked the notoriety. His behaviour is no longer under question, nor is the suggestion that he isn't anything other than remorseful. But the response is always that the welfare of the community at large, and his own personal safety. would be at risk if he was released.

So perhaps Yoko Ono was within her rights to suggest in 2010 that his release would "bring back the nightmare, the chaos and confusion once again", even if Chapman did believe that he might be able to assimilate himself once more into society. The sad truth is, the day the small part of Mark Chapman that didn't go back to his hotel won through, he probably lost forever the right to find out if he could.

The Biog

May 10 1955 Born Mark David Chapman in Fort Worth, Texas

1975 Helps out at an Arkansas resettlement camp for Vietnamese refugees but begins to struggle with mental health issues. Starts studying at a Presbyterian school in Tennessee, but soon drops out

1977 Decides to go to Hawaii to end his life, but fails in suicide bid

1979 Marries travel agent Gloria Abe

1980 Kills John Lennon on December 8. Arrested immediately and charged with second degree murder.

1981 Found guilty of murder and sentenced to 20 years to life in prison

2000 Becomes eligible for parole, and claims he is not a danger to society. He is told his release would "deprecate the seriousness of the crime and serve to undermine respect for the law". Continues bid for freedom every other year since

August 2012 Thirty-two years after his arrest, Chapman again applies for parole