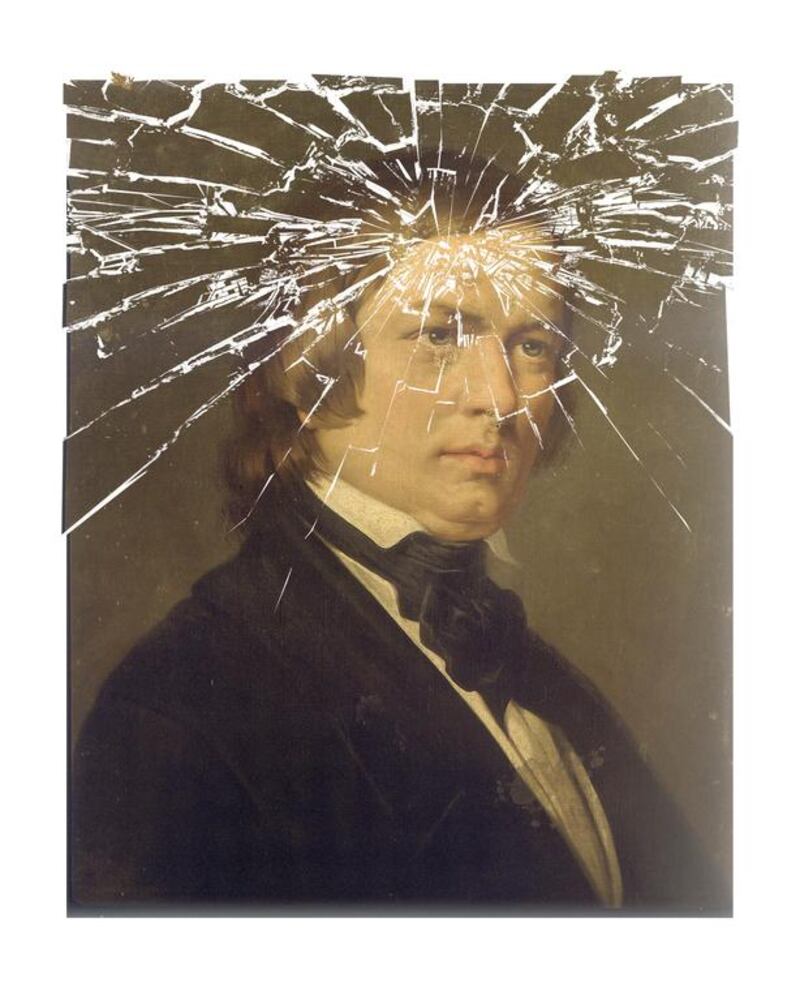

On a cold February night in 1854, German composer Robert Schumann suddenly rose from his bed and began to work.

He wanted to get down on paper a melody that was, according to some accounts, being “dictated by the angels”. Other reports suggested the composer being guided by the “ghost of Schubert”.

Either way, by morning, he had become agitated and regarded the voices as demonic “tigers and hyenas” that sang “hideous music”.

The melody – a hymn-like choral – became the basis of six piano variations, which Juan Carlos performs on his latest album, Schumann: Carnaval.

These Geistervariationen (Ghost Variations), as they became known, are the last thing the composer wrote before he was committed to an asylum.

They occupy a fascinating and disturbing place not only in Schumann’s canon, but also in classical music as a whole.

Schumann's mind had deteriorated to such a degree and he was unable to recognise that, far from being the work of angels or ghosts, the melody was in fact written by him, several months earlier, for the gorgeous slow movement of his Violin Concerto (1853).

It was a sad end to the career of a great composer, who died two years later at the age of 46.

Or was it? To some 19th-century biographers, Schumann encapsulated perfectly the most Romantic of inventions: the artist driven mad by his genius. The composer’s tragic demise and brilliant scores were viewed as somehow growing from the same root. His disturbed state of mind, an unfortunate necessity for the creativity that blossomed, was ultimately its destroyer.

This fits a narrative we see elsewhere in music, literature and on film.

We have Ludwig van Beethoven, for example, unkempt and unshaven, barking at people on the street and producing breathtaking masterpieces in the concert hall.

Gaetano Donizetti wrote some of the most beautiful “mad” scenes in opera, then ended his life confined to an asylum, unable even to talk – “surely the two are connected?” – many assumed.

And Hugo Wolf, a friend of Gustav Mahler, could compose a mountain of impassioned songs during a single manic episode, but his subsequent lows led to a suicide attempt, followed by – yes, you’ve guessed it – a one-way ticket to the asylum.

This view that creativity and madness are often two sides of the same coin persists today, and it is not hard to see why.

In Mihály Csíkszentmihályi's classic book Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention, the author describes the divergent nature of creatives – that is, their ability to view the world from a dazzling array of different angles.

“Instead of being an individual, they are a multitude,” he writes. “Creativity allows for paradox, light, shadow, inconsistency, even chaos – and creative people experience both extremes with equal intensity.”

Csíkszentmihályi was not talking about madness, but taken out of context, you might think he was.

Other common features of the highly creative include heightened perceptions, a greater sensitivity to external stimuli and persistence. They are all traits Schumann is known to have displayed, and over the years, academics and biographers have sought to find evidence of a connection between his creative personality and signs of mental illness.

At times he displayed a deep melancholia: “My heart pounds sickeningly and I turn pale…I often feel as if I were dead…I seem to be losing my mind,” he wrote when he was 18.

A year later, however, he was transformed by a manic energy: “Sometimes I am so full of music, and so overflowing with melody, that I find it simply impossible to write down anything.”

Might this be evidence of a bipolar condition? Adding weight to this argument is the fact that Schumann gave names to each side of his personality. "Florestan" was the energetic, passionate artist that could write a symphony in a staggering four days, then polish off the orchestration in the following 10 (as in the case of the 1841 Spring Symphony); and "Eusebius" was the depressive introvert.

Kay Redfield Jamison – the author of Touched With Fire, a book that explores the relationship between bipolar conditions and artistic temperament – has studied hundreds of creatives who suffered from mental illness. She told The New York Times she believes that while creativity does not depend on mental illness, it can certainly benefit from it.

“Schumann did die insane, and he did try to kill himself by jumping into the Rhine,” she said. “You have to explain how that fits into the rest of his life.

“There are so many studies now that are all finding the same thing: an exceedingly elevated rate of manic-depressive and depressive illnesses among artists, writers and composers.

“It is my perspective that the illness itself, in the context of a creative mind, can at certain times create a very definite advantage for the artist.”

Not everyone agrees with this, however. Anna Burton, an American psychiatrist, has talked of her desire “to dispel the confused idea” that creativity is related to illness.

There is even a debate whether Schumann suffered from a mental illness at all. In his book, Robert Schumann: Life and Death of a Musician, John Worthen, an academic at the University of Nottingham, convincingly refutes the assertion that the composer was schizophrenic, bipolar or clinically depressed.

Instead, Worthen argues that Schumann’s suicidal thoughts at the age of 18 were simply a common example of adolescent blues, and his subsequent bouts of introspection remained firmly within the range of “normal”.

The composer’s ultimate demise, Worthen says, was caused by the effects of syphilis, a disease that rots the mind if left untreated. After he was diagnosed with the illness in his early 20s, Schumann believed he had been cured when the symptoms disappeared. Instead, it continued to corrode from the inside, leading to neurosyphilis, the late-stage disease, which fits the tragic deterioration Schumann displayed during the last two years of his life.

If Worthen is correct, Schumann’s mental collapse was not the result of a lifelong battle with mental illness, but a biological illness. This confuses things because we can no longer assume a relationship between Schumann’s earlier creativity and his death. But could it mean we might hear a change in his music as the disease took hold?

Eminent musicologist Eric Sams believed this was possible. To back up his claim, he highlighted a set of four songs called Minnespiel (Play of Love), written by the composer in the summer of 1849 (the fourth appears in all its plaintive glory on another new release, Matthias Goerne & Markus Hinterhäuser's Schumann: Einsamkeit – Lieder, which is due in the next few weeks).

“There are ominous signs not only in the man but in the music,” Sams wrote, arguing that it is in these songs that we first begin to see the deterioration in Schumann.

But Jessica Duchen, whose 2016 novel Ghost Variations was inspired by the strange circumstances surrounding Schumann's long-lost Violin Concerto, holds a more measured view.

“Personally I think Schumann’s earlier music can sometimes sound a lot crazier than his late works,” she says, adding that perhaps what you do hear in the composer’s final compositions are his physical ailments – as much as his mental ones – affecting his capacity to “fulfil his aims”.

With the source of creativity still to be agreed upon by psychologists and psychiatrists, its relationship to mental illness remains stubbornly unclear. And so does, it seems, the debate about the effect madness had on Schummann’s music.

• Schumann: Carnaval by Juan Carlos is available now. Schumann: Einsamkeit – Lieder by Matthias Goerne & Markus Hinterhäuser will be released on April 14

artslife@thenational.ae