It is one thing to be the child of a famous musician, but quite another to be the offspring of an artist who is not only credited with inventing a music genre, but also enjoys the status of a renowned cultural and political figure.

Popular music has seen many cases where such a legacy has caused the younger generation to actively turn away from what went before, seeking out their own sound.

Bob Dylan's son Jakob formed The Walflowers, a moderately successful middle-of-the-road rock band without the political potency of his father's work.

John Lennon's eldest child, Julian, continues to carve a path in music far removed from his father's celebrated solo career and work with The Beatles.

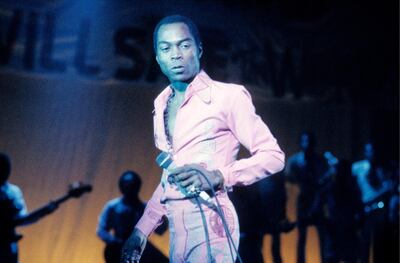

Nigerian musician Seun Kuti, on the other hand, has embraced his father's music history. The son of Afrobeat pioneer Fela Kuti joined his elder brother Femi in launching his own music career. But it is Seun, now 35, who has inherited his father's artistic baggage the most. As a teenager, he took on Fela's acclaimed backing band Egypt 80 and has gone on to release numerous records full of the bounce and political messaging that was central to his father's work. And Abu Dhabi will get a taste of his explosive live show when Seun Kuti and Egypt 80 headline NYU Abu Dhabi's Barzakh Festival on March 6.

While acknowledging his father's esteemed musical lineage, Kuti says that his legacy acts as more a support crutch than a weight.

"How could I look at it as anything other than a positive thing?" he says in an exclusive interview with The National during this past summer's Mawazine Festival in Morocco.

“I can’t say that after what my father has done for us that I am in his shadow. I just don’t see that,” he says. “My dad didn’t leave a shadow, but instead a light. It is his light that is still pointing the way forward and helping us navigate these turbulent times.”

The school of life

Indeed, Kuti grew up keenly aware of his father's musical and social influence. He was born in Nigeria's largest city, Lagos, but he grew up in the Kalakuta – Fela's sprawling compound and self-declared republic that was home to almost 300 people.

Despite the commune being infamously sacked by the Nigerian Army in 1977 – catalysed by Kuti's scathing takedown of the military in seminal track Zombie – it continues to be a home base for some family members, in addition to a museum for Afrobeat enthusiasts.

Kuti, who was born six years after the army attack, describes growing up there as educational. “I tell people that it was like the school of life,” he recalls. “I watched the way my father interacted with many people, and he was very fair and treated everyone like equals. It was definitely an education for me and anyone who spent some time there.”

A mainstay of the compound were the members of Egypt 80. Inspired by his father's performances, the young Kuti joined the band as a saxophone player and would eventually become its leader after his dad died in 1997.

Ever since, Kuti has been building a career that has successfully maintained his father's legacy, in addition to forging his own path through a discography of which Black Times is the latest. Released in March, the album is Kuti's most assured yet – and his clearest stamp of authority besides Egypt 80.

Songs that demand attention

Where previous records such as 2008's Many Things and 2011's From Africa with Fury: Rise, revelled in chaotic and almost carnival-esque grooves similar to his father's, Black Times maintains the lyrical rage, tempered by a modern, almost commercial sound.

While tracks questioning the appeal of capitalism and celebrating pro-black thinker Marcus Garvey aren't likely to appear anywhere near the playlists at your local pop radio station, the tuneful arrangements and ruthless editing of Black Times serves as a timely reminder of Afrobeat's power as protest music. Kuti says the album is indeed a call to action, and the slicker arrangements are merely a way to make the message easier to digest.

"It is ultimately an optimistic record," Kuti says. "Not every song here is about spreading a message, and it is important to say that Afrobeat music is not just that – there is some joy in there. But at the same time, with this album, it shows the political and social side of the music. Afrobeat is also about smacking someone in the face and saying: 'Wake up. What are you doing?'"

The metaphor is apt. While the songs pensively discuss the greed of corporations, the scourge of corruption and the dangers of consumerism, what binds these malaises together is the underlying cause of ignorance.

The struggle for Africa

The urgency in Black Times is palpable, whether in the shrieking horns and frenetic snares of opening number Last Revolutionary or the almost disco groove of Struggle Sounds. Kuti and his band want your attention.

The message here is primarily dedicated to Africans of all nationalities, referencing the continuous war to drain the resources of the continent, which has moved from the field into board rooms.

Awareness, Kuti states throughout the record, is the weapon to stop the tide. This is best expressed in the album's title track, which features a blistering solo from legendary guitarist Carlos Santana. Over Afrobeat's signature polyrhythmic and urgent circular guitar riffs, Kuti sings in a call-and-response fashion about the need for reflection and a true reappraisal of Africa's heritage.

________________________

Read more:

A season to celebrate at NYU Abu Dhabi Arts Centre

London’s new cool: how UK Afrobeats could take over the world

Documentary looks at the life and legacy of Fela Kuti, creator of Afrobeat

________________________

The story of the continent is not all war and famine, Kuti says – that’s only the surface. Afrobeat started way before his father, according to Kuti.

“Everybody talks about my father when it comes to that. But people don’t understand that he was inspired by my grandmother and my grandfather. They were inspired by my uncle, who was inspired by [civil-rights activist and pan-Africanist] W E B Du Bois,” he says. “This can only show that an idea that is ancient and great travels. It comes from a source. And, you know, Africa is not just the continent any more. Africa is Jamaica, Barbados, it is the United States and Europe. As an African artist, I am trying to build that bridge that carries culture to our people in such a way that it inspires to want to connect to Africa, the source.”

A major roadblock to that is the consumerism affecting most cultures and societies. In the caustic African Dreams, Kuti views it as diseases that ultimately kills innovation and creativity: "Too many youths love the television, chasing the American dream/ But what's their dream for Africa?" he steadily laments over a bluesy riff, before the horns arrive, quaking with agony.

"The way to fight this is through critical thinking. With this song, I am talking about how we should reassess the values in Africa when it comes to defining what success is," Kuti explains. "For many of the elites in Africa, they have no other expression for their success except luxury. This is despite many of them making that wealth from extraction from Africa.

Success in Africa has to mean what we can build in our communities. So when we see the elite with their big cars and yachts, things that are not really built in the institutions in their country, then we cannot see it as success. We have to see it as what it is – which is basically theft and extraction.”

The never ending tour

Kuti is weary when confronted with his own success, which is as financial as it is creative. While he acknowledges that he can live, tour the world and raise a family from his music, he is careful not to let it become the sole arbiter of his career. "Winning is also a prison, my friend," he says. "Your oppressors know how to use that language. They know how to use the jail of winning, in that they can keep telling you: 'Oh you lost.' Because you believe that you are not winning, they can change the way you think. We also have to redefine what victory is, which is that they cannot silence the idea."

Kuti is determined to perform and release albums as long as physically possible, spreading his message to as many people as he can. The UAE is a case of unfinished business for Kuti. He recalls being signed up to perform at Abu Dhabi's Corniche as part of the UAE leg of the Womad festival in 2012, but the event was cancelled. "Man, I have been trying to get there for a long time," he says. "The unknown calls me. The fact that I haven't been there and people haven't had the chance to experience my music and message matters to me deeply."

Seun Kuti and Egypt 80 headline NYU Abu Dhabi’s Barzakh Festival on March 6. Go to

www.nyuad-artscenter.org for details