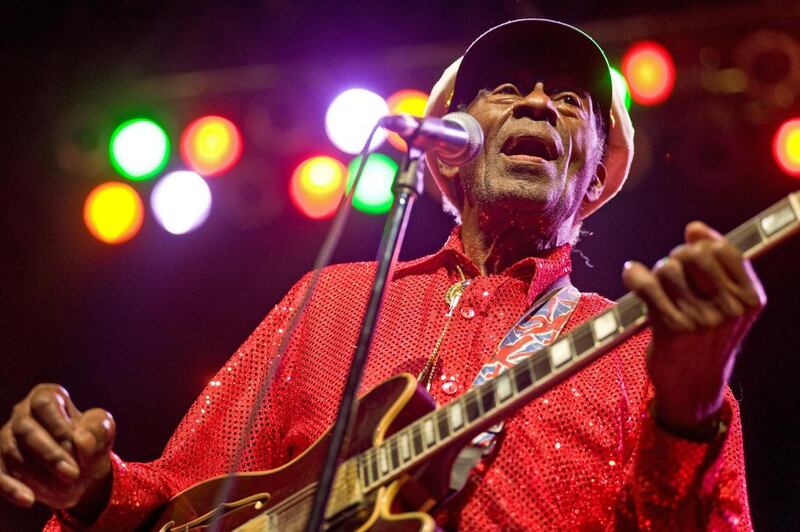

The world of rock ‘n’ roll has lost its most distinguished elder, with the passing of Chuck Berry at the age of 90 in his home state of Missouri on Saturday. Berry was not just the genre’s greatest architect, but also its archetypal great-grandfather – cranky, irreducible, immutable and utterly inimitable. Fittingly, he outlasted nearly all of his peers, still thrilling audiences onstage until late 2014. Those pioneers still standing cannot match Berry’s staggering, monumental influence on the genre which came to define the second half of the 20th century.

It might have been The Beatles, The Rolling Stones and The Beach Boys who introduced the world to rock 'n' roll, but each of them cut their teeth covering – and shamelessly imitating – Berry's pioneering work, on tracks like Roll Over Beethoven and Rock and Roll Music (both covered by The Beatles), and Carol and Little Queenie (both covered by The Stones).

Inevitably, Stones guitarist Keith Richards led the tributes, tweeting “one of my big lights has gone out” in the early hours of Sunday morning, shortly after the news broke.

Such high sentiment sounds almost an understatement – to this day, Richards’s use of slow, arching bent notes and blocked, two-string solos often sounds like something Berry might have played 50 years ago.

The master-pupil relationship was laid bare during a classic scene in Hail! Hail! Rock 'n' Roll, a documentary about an all-star concert Richards arranged to mark Berry's 60th birthday.

On camera, Berry rips into the bewildered Stone for not playing a lick quite to the elder’s liking – although it sounds fine to most ears. On another occasion, he punched Richards for touching his guitar. “Chuck’s biggest hit,” Richards later quipped.

One theory for this rivalry is that whatever praise Richards heaped on him over the years, Berry never quite forgave The Stones for becoming multimillionaires by so clearly assimilating his sound and selling it to White America.

And it was such a marketable sound — primal, youthful, cheeky, irreverent, anti-authoritarian, the voice of intergenerational revolt.

Berry’s gifts were three-fold – not just as the first rock ‘n’ roll guitar hero or even the genre’s quintessential songwriter, but foremostly, as a rock ‘n’ roll stylist. In a way that perhaps can only be compared to Louis Armstrong’s role in the evolution of jazz or James Brown in the world of soul, Berry wrote a distinct aesthetic approach that was to have tectonic consequences on contemporary culture.

The way Berry turbocharged blues forms and progressions with syncopated swing rhythms was as polarisingly potent as it was unprecedented. Yes, Elvis's earth-shattering debut That's All Right, from 1954, predated Berry's first single by 12 months – but Presley's rockabilly swagger sounds positively tame next to the distorted, fuzzy, percussive attack of Berry's guitarwork in his own debut, Maybellene.

That track announced a singular artistic vision already formed, and was followed in less than a year by both Thirty Days (To Come Back Home) and Roll Over Beethoven — a pitch-perfect teenage put-down of their parents' stuffy classical music.

This trio alone would have been enough to solidify Berry's reputation in the annals of rock folklore, but the sense of generational angst was refined further in School Day (Ring! Ring! Goes the Bell) and Rock and Roll Music, both from 1957. The following year brought Sweet Little Sixteen and the future rock 'n' roll standard Johnny B Goode.

That song's unforgettable guitar intro – built around a canny, bebop-inspired chromaticism which broke and rewrote all the rules – has appeared with subtle differences in numerous songs by Berry and others, but that iconic, stop-start riff never sounds cleaner, crisper or better stated than here. Put simply, the 12 bars that open Johnny B Goode could be stated as the very definition of rock 'n' roll.

The lyrical themes and imagery Berry tapped into – an anti-establishment ethos, youth culture, cars, a celebration of the mundane and of the moment – would come to define the very DNA pumping throughout rock ‘n’ roll’s bloodstream. Meanwhile, the muscular guitar riffs and hot-rodding of the blues he wrote make up the genre’s core bone structure to this day.

Whether or not Berry received his dues while alive might be a matter of debate. While he never enjoyed the kind globetrotting, stadium-filling success of his greatest imitators, he was already established as a legend in his fifties, and enjoyed reverential critical and audience applause until his final days onstage.

What however is clear, on the most sad occasion of his death, is that without the birth of Chuck Berry, the world of popular music would look nothing like it does today.

rgarratt@thenational.ae