Is there any genre that recycles itself as endlessly as rock music? This decade, we've seen a return to 1960s garage rock and blues, a shoegaze revival and lots of new iterations of prog, the British Invasion sound, punk and post-punk. Kasabian, who won Best Group at the recent Brit Awards, sound like a mash-up between the Rolling Stones and Oasis, a sound that's been in heavy rotation, barely updated, for the past 40 years.

But if there's one thing to give a jaded indie fan hope, it's the fact that Anglophone musicians have started looking further afield than London and New York for inspiration. This year there have been new, African-influenced albums from Vampire Weekend and Yeasayer, while Damon Albarn has been in Beirut recording with the National Orchestra for Oriental Arabic Music for the new Gorillaz album, Plastic Beach, which is released worldwide next week.

British and American bands borrowing from global sounds is, of course, nothing new: from the Indian influences on The Beatles, dating back to 1965 and the sitar on Norwegian Wood, to Paul Simon's South African-inspired Graceland. But, until recently, it fell out of fashion in a big way, and albums such as Graceland were written off as sanitised backpacker music written by earnest tourists with no real understanding of the cultures they were plundering.

"World music" itself became an awkward, un-PC term in the 1990s, and the former Talking Heads frontman David Byrne, who set up his label Luaka Bop to promote non-western bands, wrote an article called "Why I Hate World Music" in 1999. "Exotic and therefore cute, weird but safe" is how he thought most people interpreted the catch-all category. "Maybe that's why I hate the term. It groups everything and anything that isn't 'us' into 'them'."

Since then, there have been plenty of crossover collaborations that have erased that divide. Damon Albarn has been a pioneer: from 2002's Mali Music, recorded in the West African country with local musicians; to 2007's The Good, the Bad and the Queen, recorded with the Afrobeat drummer Tony Allen; through to the forthcoming Gorillaz album and its Lebanese choir, he's managed to make cultural mash-ups sound less like tourism and more like genuine experimentation.

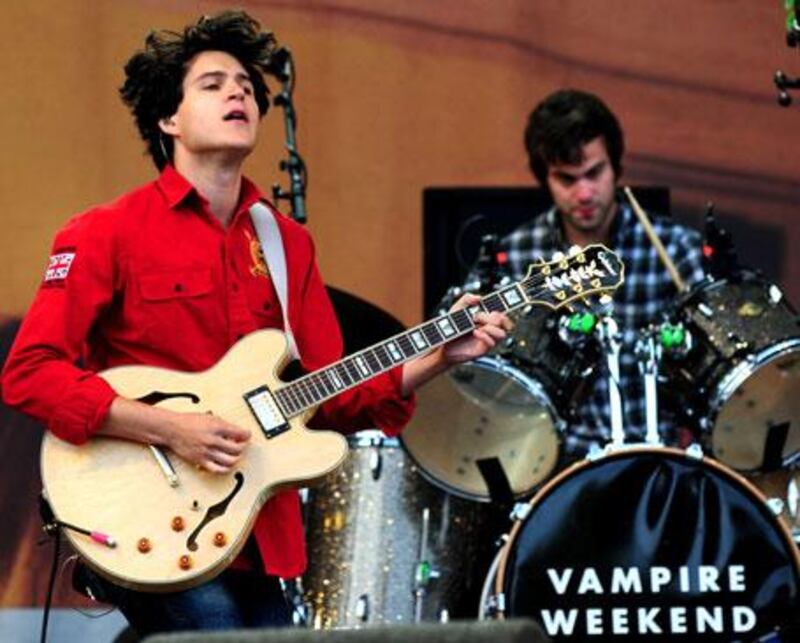

Then of course, there's Vampire Weekend, whose Congolese-inspired first album, self-described as Upper West Side Soweto, came out to a mixture of derision and acclaim in 2008, and whose similarly flavoured follow-up came out this January. The combination of their New York background, natty hipster clothes and the African references in their movements saw the term "passport rock" being lobbed their way as a criticism, but the band opened the floodgates for a new wave of US and UK groups to start dabbling unself-consciously with (previously deeply unfashionable) global sounds.

Since then, Afrobeat and the influence of other global sounds on indie music has been a trend that's yet to fizzle out. The jubilant Brooklynites Yeasayer, the math-rockers Foals and the prog-jazz experimenters TV on the Radio have been embraced as part of the same movement as Vampire Weekend, while the likes of M.I.A. and, more recently, Major Lazer (made up of the producer duo Diplo and Switch) have mashed up western pop and electro with music from India, Trinidad, Liberia and Jamaica.

Meanwhile, El Bronx (yet another gang of fashionable guitar-toters from Brooklyn) have been embracing traditional Mariachi sounds for their album Mariachi El Bronx, released towards the end of last year, which used Mexican instruments such as the vihuela, jarana, ukelele, and requinto. The Houston-born indie flower child Devendra Banhart is also still touring his 2009 album, What Will We Be, which mixes Brazilian music with bluegrass, reggae and folk, and includes a song sung mostly in the lost language of the Pit River Indians. It's hard to get more multicultural than that, although critics are on the fence as to whether Banhart manages to mould the disparate elements into a whole worth listening to.

Stuart Clarke, the talent editor of the British music trade magazine Music Week, says: "I think music is crossing over more than it ever has. He puts this trend down to the globe-shrinking power of the internet. "People's access to music has opened up," he says, "and that is bound to have an influence on music being created. Websites such as Pitchfork and Drowned in Sound, as well as lesser-known blogs, mean it's far easier now to be exposed to artists who occupy more of a niche space and which in the past perhaps took a bit more discovery."

This ability to discover niche music from around the world without leaving the house doesn't just mean that musicians' set of influences can get more eclectic. It also means that all of us can add West African hip-hop, Inuit choral music and Indian ragga to our record collections. Whereas the typical High Fidelity-style music snob used to obsess over his knowledge of obscure B-sides from the 1960s, to stay hip these days you've got to prove an understanding of underground bands from remote corners of the globe.

There are plenty of signs that non-western music is being appreciated more and more in the UK and US for its artistic merit. In November, the rock music magazine Uncut awarded its Best Album award to the Saharan collective Tinariwen, who mix the blues with Middle Eastern and African sounds. The musicians faced competition from the likes of Bob Dylan and Kings of Leon: they weren't relegated to a separate "world music" category. Uncut's editor focused on the band's universality - rather than their differentness - when he explained the choice, saying that their music "speaks a common language".

The global music scene is shrinking, and sounds from all continents being spliced up and stitched together in new ways isn't just sonically exciting, it can also make people more politically aware. In an interview with Pitchfork last year, Albarn talked about the importance of cross-cultural understanding in a changing world. "We really need to understand that [China's] destiny and our destiny and Africa's destiny are all completely tied in," he urged. "The argument for getting to know your neighbours is very compelling."