Two questions whisper themselves after an initial orbit of Tate Modern's celebration of Roy Lichtenstein, the first comprehensive retrospective of the pop artist's work since his death in 1997.

They are: 1) Where is everybody? and 2) Where's that one with the fighter pilot shooting down an enemy jet?

The answer to the first question lies in the answer to the second - and out of both sprouts a third: what is the point of a retrospective?

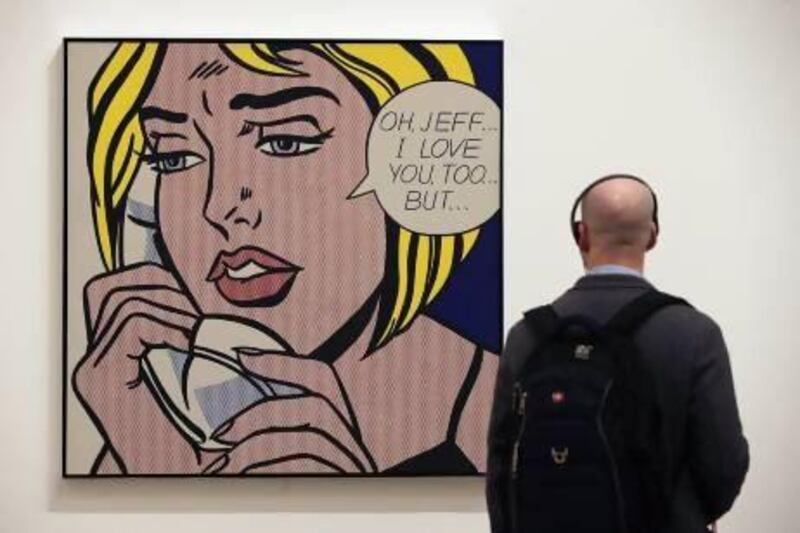

For most people, though they might not readily recall the names of the pieces themselves, Roy Lichtenstein is Whaam! (1963) and, perhaps, Oh, Jeff … I Love You, Too … But … (1964), images appropriated from comic strips, blown up to epic proportions and subjected to the artist's trademark application of dots in imitation of the Benday printing process.

By zooming in on and fetishising the banality and trivialisation of the everyday - romance, household objects, advertising, the sterilised portrayal of war - Lichtenstein was, quite literally, exercising a postmodernist rejection of modernism. Look closer, he seems to be saying, and you will see that the landscape of modern life is nothing but an illusion.

But was that it? Was Lichtenstein nothing more than a one-trick pony, to be consigned to history as the pop-dots guy, aloft on a monopod pedestal set alongside those of Andy Warhol, the soup-cans guy and Damien Hirst, the pickled-shark guy?

Perhaps the organic, democratic judgement of posterity, a kind of multi-source aggregator that automatically samples cultural references in order to boil down a lifetime's work to one or two "iconic" pieces, is all that matters - and maybe an artist (or, indeed, any one of us) ultimately gets lumbered with the narrowly focused, aggregated legacy they deserve.

Maybe. But the Tate art gallery in London deserves full marks for questioning the appropriateness of this fate for Lichtenstein - and, by association, for all artists.

*****

It is, perhaps, no accident of the slightly perverse topography of the 13-room wing of Tate set aside to house the more than 160 works created by Lichtenstein between 1950 and 1997 that the artist's pop hits have to be actively sought out.

Tate, working with The Art Institute of Chicago, conceived the Lichtenstein retrospective as "a long overdue reassessment of his artistic achievements, exploring both famous and little-known aspects of his work". If Lichtenstein "somehow does not need an introduction", as the show's co-curator observed on her blog, that is only because most of us think we know all there is to know about him. It would, of course, have required commercially suicidal courage to have selected an unknown work for the Lichtenstein poster, and Tate is nothing if not savvy. It was, after all, one of the first institutions to spot Lichtenstein's potential, snapping up Whaam! in 1966 for about £4,000 (Dh22,500).

But, having got the punters through the door with a whiff of the greatest hits, Tate's curatorial integrity reasserts itself in a thoroughly impressive manner.

You come face to face first with three mighty canvases, any one of which might have staked Lichtenstein a claim to fame. These are from his Brushstrokes series, painted in 1965 and 1966 - after the bulk of the iconic cartoon-strip work, which Lichtenstein had given up altogether by 1966.

The effect of stumbling upon these impressive pieces as the exhibition's opening statement is bewildering and effective - not unlike attending a classical concert to find the orchestra has swapped the dramatic and universally familiar opening bars of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony with those of the more elegiac and thought-provoking second movement.

In style, colour and technique, Brushstrokes (1965), Little Big Painting (1965) and Brushstroke with Spatter (1966) are instantly recognisable as Lichtensteins - and yet simultaneously jarring for being devoid of familiarity.

And there is much more to come. After all, these paintings were made not at the apogee of a career, but three full decades before the unexpected death of a physically robust artist who remained energetically prolific right up to the end, at the age of 73, in 1997.

Who among Lichtenstein pop-art poster-buyers at large knew, for instance, that the artist worked so extensively and convincingly in black and white, objectifying and elevating everyday objects - a radio, a ring, a golf ball, a tyre, a ball of string?

Most fascinating of all, perhaps, is Lichtenstein's early, pre-Whaam! work - largely untitled powerful adventures in abstract modernism, devoid of dots and demonstrative of a young artist confident with form and colour but groping his way towards his own style.

It is, in fact, only when visitors are three or four rooms into the exhibition that they pull up short, remembering that something seems to be missing.

Consulting the exhibition floor plan, it becomes apparent that one gallery - the largest, containing Lichtenstein's most familiar work - has been unwittingly bypassed.

Footsteps must be retraced. There are two entrances to this central room, but it is testimony to the gravitational pull of Lichtenstein's "unknown" art - and to the cunning of the curators - that it has hauled the majority of punters right past them.

Here, then, can be found Whaam!, Oh, Jeff, Drowning Girl (1963) et al, and here too, finally, can be found the crowds, jostling to take comfort in proximity to the familiar.

Locating these pop gems in an off-Broadway cul-de-sac takes courage, not least because it was Tate that helped to bestow iconicity upon the art within, and the artist, when it bought Whaam! in 1966.

And Tate's unflinching curatorial courage does not stop at manipulative interior design.

For those in the know, Lichtenstein's "inventiveness", in the words of one of the essays in the show catalogue, is "rooted in imitation; he transformed the very idea of borrowing into a profoundly generative, conceptual position, one that alters the trajectory of modernism, and beyond".

But this show, with its admirable mission to spread before us the full expanse of Lichtenstein's career, is for those not in the know - and for many gathered in the central shrine the Tate decision to display alongside Whaam! a copy of the January 1962 edition of DC Comics' All-American Men of War from which Lichtenstein "borrowed" his defining image provokes a somewhat less hagiographic response.

In the few minutes I stood by the glass case in which the open comic is reverentially displayed, no one talked about "the recomposition of found imagery". The words muttered here by Lichtenstein ingénues included "nicked" and "stolen".

And in this inner sanctum, at the inverted heart of the show's bold inside-out approach to fame, can also be found a wider, intriguing question: is the role of a retrospective to consolidate the legacy of an artist - or to reconstruct it?

*****

"There are many intentions," says Iria Candela, the Tate curator who worked on the show with colleagues from The Art Institute of Chicago, where it was exhibited first.

"Of course all the clichéd assumptions of blockbuster exhibitions come to the fore. This is a very famous artist from the pop art generation. What can we add that would complicate or enrich the perception of his work and his legacy?"

To answer that question, when Candela and colleagues sat down four years ago to begin planning the retrospective, they made the decision to set aside all the accepted wisdom and to look for themselves at every piece of work Lichtenstein had produced.

"We just tried to understand his evolution and to rescue all the significant moments of his career," she says. As they did, they were "struck to find many beautiful series of works, such as the Chinese landscapes, that people who are in the field were aware of, but in general the public didn't really know".

*****

By chance, London is currently in the grip of another major retrospective, dedicated to another kind of iconic artist, which also offers some clues about the nature of artistic retrospection.

David Bowie Is, at the Victoria & Albert in London, is a celebration in costume, sound and vision already defined by advance ticket sales as the most popular show ever staged by the museum.

There is, of course, a slight difficulty inherent in staging a retrospective of a still-active artist - a difficulty that Bowie himself emphasised when, to the surprise of everyone, including the V&A team, he suddenly awoke in January from an apparent creative coma to release a new single on his 66th birthday.

And Where Are We Now? was merely the vanguard of an entire, equally unanticipated album. Doubtless both Bowie's sales and those of the V&A's ticket office have benefited from the sleight-of-synchronicity - the show is the fastest-selling in the museum's history and The Next Day has topped the UK album charts. But one can only imagine what the V&A team made of the cover of the album, which perversely seemed to undermine the very idea of staging a definitive retrospective.

It took the cover of his 12th album, Heroes, released in 1977, but with the title crossed out and the main image, of the man himself, overlaid with a white square bearing the words The Next Day.

"Normally," blogged Barnbrook, the London design group responsible, "using an image from the past means 'recycle' or 'greatest hits', but here ... the Heroes cover obscured by the white square is about the spirit of great pop or rock music, which is 'of the moment', forgetting or obliterating the past."

But in the same breath, the team conceded a kind of circular defeat: "However … no matter how much we try, we cannot break free from the past … When you are creative, [the past] manifests itself in every way - it seeps out in every new mark you make. It always looms large and people will judge you always in relation to your history, no matter how much you try to escape it."

Bowie is, of course, known for his chameleon-like changes. But the danger of an exhibition such as this, in assembling a collage of his styles and influences, is that Bowie the musician emerges somewhat diminished by the effort to establish him as something more than that. The songs drift inconsequentially in and out of the headphones as one wanders from room to room, and they become little more than a soundtrack for a collection of photographs, film clips, memorabilia and stage-tarnished costumes.

And the context - blockbuster retrospective exhibition, complete with blockbuster (2kg) catalogue - provides as much pretentious, retrospective nonsense as it does illumination.

Take Nicholas Coleridge's appreciation of the countless promotional photographs snapped of Bowie over the years: "Somehow," muses the V&A trustee, a standard-issue 1966 "mod-look" shot of a 19-year-old Bowie "in its brooding existentialism, presages the whole later period of his life in Berlin".

Really? Or perhaps it merely shows Bowie for what he then was - a do-anything-for-fame Anthony Newley wannabe novelty act following the hairstyle trend of the moment and struggling for credibility with such dreadful aberrations as the oompah-assisted Rubber Band and the timelessly offensive, pun-infected The Laughing Gnome.

Gnomes, funnily enough, play very little part in this show.

*****

David Bowie Is is the retrospective not only as celebration, but as a determined attempt to elevate its subject beyond the undeniability of his claim to having written several good and a few great pop songs. The Beatles, he is not. Yet in the words of the curators, he is "the most significant musician of his generation" whose "influence in the wide arena of performance, fashion, art, design and identity politics continues to shape contemporary culture in the broadest sense".

But even though this exhibition has been mounted with the full support of the "official Bowie Archive", it demonstrates, as only a retrospective can, that ultimately all artists lose control of their work and how it is seen by subsequent generations.

Unlike Lichtenstein, Bowie still lives, of course, but his contemporary voice is as absent from David Bowie Is as was the man himself from the exhibition's opening night.

The last word in the catalogue goes to Mark Kermode, a British film critic and broadcaster. Suggesting during a critics' round-table discussion that, "in a way", it no longer mattered what Bowie intended when he created his work, he hit the retrospective nail on the head.

"Everything … has been so pored over and so personalised that it doesn't matter what he thinks," he said. "It doesn't matter what he meant when he wrote Heroes, and it doesn't matter what he thought when he did the cover photography for The Man Who Sold The World … I think we own the Bowie back catalogue more than he does."

This chimes with the thinking of Lichtenstein's philosopher-contemporary Roland Barthes, whose seminal 1967 text, Death of the Author, argued that "To give a text an author is to impose a limit on that text".

*****

The Tate's Candela sees much of Lichtenstein's work, especially his mirrors series, with their absence of a reflection of either viewer or artist, in the context of this contemporaneous avant-garde thinking. Music, painting, literature - all such creative work, she says, is thus freed to be "constantly read and understood differently according to the context and [the reader's] social co-ordinates … Audiences change, and their knowledge and perceptions also change."

Such fluidity of meaning and interpretation is a relatively recent relaxation of the rules that has made it possible for an arrangement of bricks or a pickled shark to be granted cultural significance comparable to that of a Mona Lisa or a Water Lilies.

It is also something of which Bowie (once, at least) approved. Compare two quotes currently to be found on display within the V&A.

One is the inscription above the museum's main door arch, derived from the words of Sir Joshua Reynolds, the 18th-century British portrait painter, as a kind of mission statement for the V&A when it opened in 1909: "The excellence of every art must consist in the complete accomplishment of its purpose."

Presumably Reynolds and the V&A's founding board will be undergoing choreographed grave-spinning at the counter-thoughts of David Bowie, which greet all visitors to his retrospective: "All art is unstable. Its meaning is not necessarily that implied by the artist. There is no authoritative voice, there are only multiple readings."

One artist who has been denied the luxury of popular readings is Yoko Ono who, in terms of her own artistic identity, had the misfortune to marry John Lennon. The former Beatle, who recognised that the vastness of his fame would always leave Ono's self-expression in the shade, called her "the most famous unknown artist in the world".

Now Ono finally has her own retrospective, at Frankfurt's Schirn Kunsthalle museum until May 12, after which it will visit Denmark, Austria and Spain.

This is not the Ono of bed-ins-for-peace fame, or the Ono who was Lennon's partner in crime in supposedly breaking up The Beatles. This is the Ono of such avant-garde works as Instructions for Painting (1961) and Cut Piece (1962), the Ono who, according to the Schirn Kunsthalle's curators, was "one of the most influential artists of our time".

Seven years older than Lennon, Ono was already an established avant-garde and conceptual artist in New York by the time they met. Her first exhibition was in 1961 - two years before The Beatles had their first number one single. Now, in her 80th year, the retrospective is a chance to reaffirm her significance as an artist in her own right.

"She is familiar to practically everyone, yet only very few people are fully aware of the outstanding artistic oeuvre she has created," writes Max Hollein, the director of the Schirn Kunsthalle.

Ono's own comment on the Half-a-Wind Show was more plaintive: "This is about 40 to 50 years of my life," she says in a video letter. "I am a very active artist - each year I have made so many things."

The Schirn Kunsthalle retrospective, says Candela, is a tremendous opportunity to educate people about Ono's work, as opposed to her reputation, and chimes with "one of the missions of Tate [which is] precisely to uncover hidden stories and to bring to the mainstream figures such as Ono and Yayoi Kusama".

Kusama, the subject of a major show at Tate last year, forms an interesting fourth overlapping circle in a retrospective Venn diagram linking Lichtenstein, Bowie and Ono. Like Lichtenstein, she worked with repeating dot patterns; like Bowie, she constantly reinvented her style; like Ono, she is from Japan and was a major player in the New York art scene of the 1960s, though not one appreciated by a wider public.

Kusama's show "was very popular, a great success", says Candela. "And even with very prominent figures like Lichtenstein we still attempt to reconfigure the assumptions people have about artists, because the history of art is constantly being rewritten; there is not really a prevalent stable narrative now about art."

*****

The retrospective alone, of course, cannot be expected to do all the heavy lifting. Much comes down to timing, luck and historical insight. When Tate bought Whaam! for £4,000 in 1966 "we were lucky" admits Candela. "It was a controversial acquisition. There was a lot of opposition within the committee because the work was considered too contemporary, and they didn't understand it."

They would understand it now, all right. Over the past three years the record for Lichtensteins at auction has risen three times, culminating last May - shortly after Tate announced its current retrospective - in the sale of Sleeping Girl at Sotheby's in New York for US$44.9 million (Dh164.9m).

Curators, of course, like to think outside of the wallet.

"Tate is part of the consensus that legitimises the work of an artist," concedes Candela. "But now we are trying to challenge people's expectations and knowledge by saying Lichtenstein is, of course, one of the foremost pop artists, responding to the boom of consumer culture at the time in America, but then further on his career extended far beyond that period. He did much more which is important for the understanding of the evolution of painting in the 20th century."

Lichtenstein, says Sara Doris, an assistant professor of contemporary art history at Northeastern University, Boston, would have approved of that take on his work.

"Lichtenstein felt strongly that he continued to improve as a painter and as an artist and so one of the things that this retrospective is trying to do is underscore that he continued to create major works and that his work evolved," she says.

It is, of course, impossible to imagine, but what would survive now of Lichtenstein and his reputation if one were able to delete the five-year period, 1961-66, in which his most famous works were created?

"That," says Doris, "is an interesting question. It was a crossover moment Lichtenstein had because he was using a kind of language and style and imagery that connected with the popular culture at a moment when youth culture was exploding in the United States."

Without that - without the war and romance paintings - "I think he still would have had a reputation in the art world, but I don't know if he would have attained the kind of popular awareness that he did. Those works were a necessary bridge for him, because they were a way for him to walk away from modernism."

The rest, of course, is art history, but it was all still up for grabs when "Roy Fox Lichtenstein, painter and sculptor", was interviewed in his studio on New York's West 26th Street at the end of 1963 as part of the Archives of American Art's oral history programme.

Famously, the interviewer, art collector Richard Brown Baker, suggested "it might become burdensome after another 20 years, if you get to be as famous as Picasso or something", to which Lichtenstein - who, despite his rejection of modernism, never lost his admiration for Picasso - replied: "That's the best kind of burden I can think to labour under."

But concealed within the 158 pages of the transcript lies the revelation that the ultimate "new realist" was, from the very outset, as realistic as David Bowie about the chances of the meaning of his art surviving contact with posterity - and the retrospective.

"My purpose is entirely aesthetic, and relationships and unity are the thing I'm really after," he said. "Whether I succeed or not, of course, I suppose will be up to history."

Lichtenstein - A Retrospective is at Tate Modern, London, until May 27, when it transfers to the Pompidou Centre, Paris, from July 3 to November 4.

David Bowie Is is at the V&A, London, until August 11.

Yoko Ono's Half-a-Wind Show retrospective is at Frankfurt's Schirn Kunsthalle until May 12, after which it will tour to major museums in Denmark, Austria and Spain.

Jonathan Gornall is a regular contributor to The National.