It really is a shining example of hope over experience. The reunion of the Stone Roses this year for their Third Coming tour - a typically sardonic reference to their indifferent Second Coming album in 1994 - has not been without its challenges.

This is a band that imploded after just two albums, and whose live performances were notoriously unreliable, yet when their 2012 world tour was announced, tickets sold out in less than an hour. Their tour is accompanied by a number of exhibitions and books, including a display of images in London, at Whiteley's, by Kevin Cummins, Ian Tilton and Paul Slattery, the three photographers whose shots defined the band almost as much as their music did.

"Every band needs great images," says Tilton. "The Stones did it, The Beatles did it ... A lot of people see the photo before they hear the music."

As photographers for music magazines including NME and Sounds, Tilton, Cummins and Slattery had the best seats in the house from which to view the rise and fall of the Roses, from their turgid goth glossiness of the mid-1980s to the arguments that led to the band's demise a decade later. And as experienced rock photographers, they instinctively knew when the band had turned into something that would influence British music for decades (try to imagine what Oasis or Kasabian would sound like without the Stone Roses, or how Liam Gallagher would look without Ian Brown to ape).

"A lot of bands that were coming out of Manchester at that time - like The High, Northside and so on - while they might have had one good song, the Roses had a great set list," says Cummins. "They were exciting and they looked good and Ian was a great frontman and John knew how to play the guitar. They were a band that people wanted to go and see very quickly."

Both Tilton and Cummins are from Manchester, and both say that gave them a head start in creating a rapport with the band.

Cummins, who has photographed everyone from David Bowie to Joy Division, was working for the NME at a time when it was still essential reading for music fans. The fact that he'd worked with some of the Roses' favourite artists endeared him to them; the result was that this often-awkward band invited him into their world and he got some of the most famous shots in the band's history - including the four members covered in an abstract expressionist mess of blue paint, in the style of one of John Squire's paintings.

"When we did that shot we were doing an on-the-road piece with them in Amsterdam, and trying to get bands together on tour is tough. They all get up at different times, and invariably about three minutes before the coach is due to take them somewhere else. There's a lot of hanging around, and I didn't really feel I'd got a cover shot. What I wanted to do with them was a career-defining image. So I felt to photograph them like a John Squire painting was bringing different elements into the picture. In the end it's become a picture that defines them. You look at that picture and you know what they're going to sound like as well."

Tilton, too, was a Mancunian, and he used this to build trust with the band. "You have to connect on a personal level with them, otherwise you won't be asked back," he says. "Their whole ethos was to use a crew that were friends; all their roadies were their friends."

Indeed, Tilton's photography was often executed as much for the experience as for money. "We didn't think about how much we were earning from it - we were all happy to just create something good. Like with the album shoot, they just said, 'We're gonna be filming tomorrow, bring your camera if you're free'."

But staying on the right side of chummy can be a balancing act, says Cummins. "When you see bands falling apart, it's quite difficult because I've worked with them a lot, and I like them individually, and you almost want to gather them together and say look, it'll work out. But I have to not get personally involved, else you end up taking sides and it gives everybody somebody else to blame, really. So I think: stand back and watch with interest, generally."

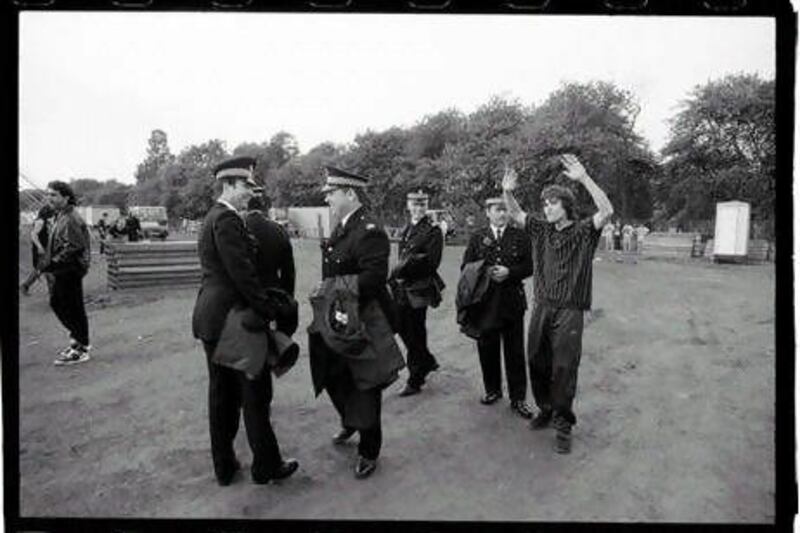

When the chemistry works, though, the result is magical: if Cummins's paint shot is one of the defining shots of the Roses, another is Tilton's "monkey-face" shot of Ian Brown, so evocative that it was used on the back of their first eponymous album and inspired his whole "King Monkey" persona. In the exhibitions it is shown as part of a chronological series, revealing the process of securing a truly great photograph.

"I lit the scene really beautifully," says Tilton, "because it was a shoot for a front cover, and I said to Ian, 'OK, we need to bring this to life now', and Ian pulls the monkey face just for a laugh.

"Some photographers would just let that go, because for a handsome fella to pull that monkey face is so uncool, but I said, 'That's great, that's it, do more of that.' So he got more into it, and he waved his arms in the air, and he pulled a face, and he was kind of dancing around and his eyes went wider.

"But the first photograph was the best; there was something about his eyes not being manic that just worked, and in the background John was smiling, and in all the photographs after that he wasn't. He's still called King Monkey, isn't he?"

The irony of a band with such a tiny output being the biggest music news of 2012 comes as little surprise to either Tilton or Cummins.

"I've always loved the Roses and thought there's probably more to come," says Cummins. "There are bands that I think should probably never reform, but I don't think they ever finished what they started. I think they made one and a half good albums, so I think there's more to come and I'd like to hear what that is."

For Tilton there is a more emotional reason for the success of the reunion. "I think it's that people have connected with an attitude of love that the band give out," he says. "It is a wee bit hippy, but it is genuinely true that Ian's lyrics are about unity, and not in a vacuous way. I think Ian's an honest man, and people connect with that. There's a lot of love from the audience that's genuinely reciprocated.

"The Stone Roses are played at people's funerals; they've been significant tracks to people's lives. And it stands the test of time. It's got integrity, great melody and harmony."

The Stone Roses: The Third Coming is on show at Whiteley's, London, until August 12.

Gemma Champ is a former arts & life editor at The National.