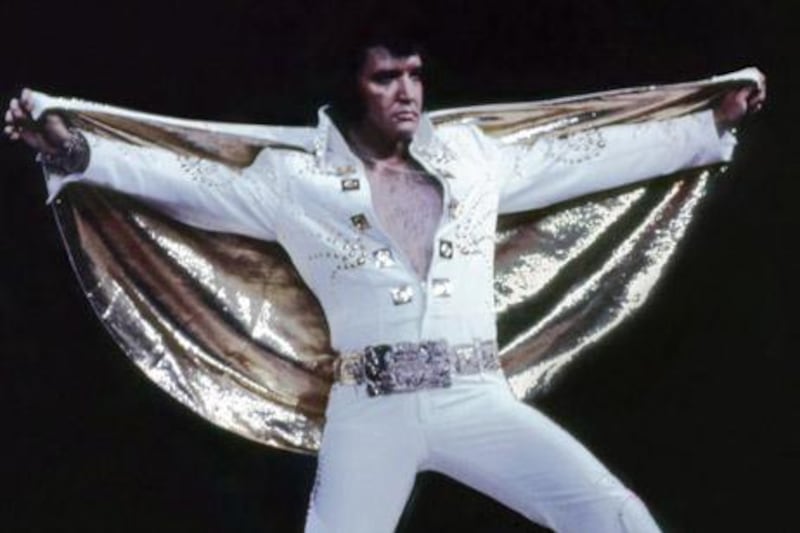

The only mode of dress more absurd than the white jumpsuit sported by Elvis Presley in the 1970s is the same jumpsuit, in all its glinting flashiness and wide-collared glory, ringed with the flowers of a Hawaiian lei. Any man of distinction at the time had to wear a lei from the moment he stepped off the plane in Honolulu, presumably. But still: Elvis in full stage dress adorned with tacky floral decoration would bring tackiness to new extremes.

That doesn't mean he lost his capacity to rock, though. And rock he did in a pair of live-wire concerts compiled for a new two-CD edition of Aloha from Hawaii via Satellite. The performances were notable when they happened, in early 1973, for being broadcast on television all over the globe, in an era when satellites were not yet standard media fare. They were seen and heard by "one-third of the world's population", according to the new set's liner notes, and "the media reaction to Elvis having made television and entertainment history was one of respect and admiration".

This was not easy for Elvis to achieve at the time. His career, if not exactly in tatters, had been erratic for several years already. His weight had begun to fluctuate, and just two years before, he had arranged to meet US President Richard Nixon for a discussion about his enlistment as an agent with the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs, the predecessor of the DEA. The Elvis of 1973 was no longer the Elvis of humble southern charm and sleek, sexy rock 'n' roll. And yet, as evidenced by his musical presence in Hawaii, he was. After the otherworldly bombast of taking the stage to Also Sprach Zarathustra (the theme from 2001: A Space Odyssey), Elvis tears into a version of See See Rider with a crack band playing nimble backing lines answerable to demands for a dense spectacle of sound and a hardscrabble honky-tonk charge. Guitars peal off riffs and horns blare all around, as Elvis bellows and strikes breathless coos with a sense of tight theatricality and play.

By the second song, Burning Love, a timely comeback hit when it was released just a few months before, the set is already alight with a fleet funk energy. Basslines don't get much better than the bouncy one tracked like a heavy burden beneath Burning Love, but Elvis's voice wanders weightlessly through all its different registers above. He sounds insanely dynamic and vibrant, enough to make even the most resolutely scoffing sceptic wonder about the conventional storyline that casts Elvis in the 1970s as a bygone legend already in a tailspin. Storylines, of course, stuck to Elvis whether or not they were true, and there may no longer be a single conventional one with so many years now separating fiction and fact. Was Elvis really high when he met Nixon? Did he really eat sandwiches slathered with peanut butter, bananas and bacon? Did he really die on the toilet? Did he even really die?

Maybe, maybe not. Beyond question is how lively Elvis was on the night of January 14, 1973, especially when he was performing Suspicious Minds, an epic song set afloat with a spirited sense of levity. Sounding a little winded from all the fun he's having, Elvis switches up the lyrics near the end, singing, "Caught in a trap, I can't walk out - I hope this suit don't tear up, baby."

Or, with emotions pitched down, in I'm So Lonesome I Could Cry, a classic Hank Williams tune that Elvis introduces as "probably the saddest song I've ever heard". In his gentle, warbling delivery, you can hear Elvis commune with his country roots in the rural American South - so far removed, in every sense, from where he is on stage in Honolulu. The same goes for a different stage he commands on another recent archival release, Prince from Another Planet, recorded at New York's Madison Square Garden in the summer of 1972. The four concerts from which the two-CD set was culled were the only ones that Elvis ever played in New York. He had performed in the city for the taping of famed TV appearances on The Ed Sullivan Show in the 1950s, but none had been open to the public - and they were certainly not on the scale of an arena show attended by 20,000 people.

Predictably, the presence of Elvis was surrounded by much big-city fanfare. At a press conference before the shows - included in a DVD documentary packaged with the two-CD set - the King says, laughingly, "We had to wait our turn to get into the Garden". In answer to a question about the image he had established, Elvis says: "Well the image is one thing, and a human being is another, you know."

Both are in action in Prince from Another Planet, which bears similarities to but is significantly different from Aloha from Hawaii. The set list is much the same and even the "hope this suit don't tear up, baby" quip from Suspicious Minds carries over. But the recordings from New York are more rocking and raw, with a more electrifying feel.

After the same Also Sprach Zarathustra opening, even more bombastic as it booms through the cavernous arena environs, the band launches into That's All Right, monumental for being the first commercial single that Elvis ever released. The song was a stripped-down rockabilly ode in its original incarnation in 1954, but it's much bigger here, with horns blaring and a chorus of background singers adding accents to Elvis's throaty voice.

"It just died, didn't it?," Elvis says once the song comes to a close and quiets down completely. But then the band bursts back to action with an even more rollicking cover of Proud Mary by Credence Clearwater Revival. ("Rollin', rollin', rollin' on the river," indeed.)

It's striking, with someone so formidable for a frontman, how much the band as a whole sounds like a cohesive, interlocking unit. In a savage version of Polk Salad Annie, another cover that traces back to swamp-rock artist Tony Joe White, the band bears down and lays into some good, greasy riff-rock with flights of instrumental fancy - drum fills, fuzzed-out electric bass, flecks of wah-wah guitar - soaring off this way and that.

The effect is especially pronounced in a medley of golden-oldie Elvis classics such as All Shook Up, Heartbreak Hotel, Love Me Tender, and Blue Suede Shoes. With the first notes of each, the crowd freaks out fully, screaming as if for The Beatles.

"He was a little bit apprehensive that they might not like him," says piano player Glen D Hardin in the documentary. "I don't know why he thought that, but he did." Elvis needn't have been nervous. "He functioned as a god," says Larry Kaye, reminiscing about the run of shows he covered as a young rock journalist at the time.

Elvis was in fact a god to some - but a wry, knowing sort of one. In a spoken introduction before Hound Dog, he addresses the microphone with a sly aside: "This is my message song for the night." So soon after the heavy, heady mood of the 1960s, the notion of the "message song" carried a lot of weight. Of course, Hound Dog had no clear message to speak of. But that didn't keep Elvis and the band from tearing through it with searing intensity, presenting it as if it was an urgent manifesto.

"You ain't nothing but a hound dog, crying all the time," the King sings. Was he directing his sentiment to a waning generation that had protested too much? Was he laying into himself for having fallen out of action for a few years before? Was he hamming his way through a healthy and nourishing bit of good rock 'n' roll nonsense?

Maybe it was all three, or none at all. With a figure as enduring and ethereal as Elvis, it's hard to know - and always rewarding to wonder.

Andy Battaglia is a New York-based writer whose work appears in The Wall Street Journal, The Wire, Spin and more.