It's mid-afternoon on Saturday at the UK's Reading Festival, and on the main stage, the New York band The National is blazing through the highlights of the recent album High Violet to a swelling crowd. Their songs are suffused with a very adult melancholy - "With my kid on my shoulders, I'll try/Not to hurt anybody I like", sings Matt Berninger on the tense, alienated I'm Afraid of Everyone. Still, they approach their set with a broiling energy.

In between swigs from a glass, the black-clad Berninger thrashes round the stage, mic stand clenched in one hand, and the band soldiers towards grand peaks.

Behind and to the left, the Festival Republic tent is packed, bodies tussling to squeeze under the canopy. Inside is Little Roy, a reggae vocalist in his 70s from Kingston, Jamaica. He and his band play sweet reggae in the roots mould, but there is something here to make your ears do a double-take. "Mom and Dad went to a show/Dropped me off at Grandpa Joe's/I kicked and screamed, said please don't go," trills Roy, and the backing singers sing "woah-woah" in chorus. The song is Sliver, but the narrator - this tantrum-prone child - is not Roy himself, but a boy from Aberdeen, a blue-collar town in Washington state, who grew up to be the lead singer for the band Nirvana.

Roy and his band are here to promote Battle for Seattle, a collection of cover versions of songs by Nirvana, which reached a tragic end in April 1994 when the frontman and songwriter, Kurt Cobain, took his own life. The project was arranged by Mutant Hi-Fi, aka Nick Coplowe, a sometime sound engineer for UK reggae great Adrian Sherwood.

Coplowe talks of reggae's lyrical legacy of "suffering and struggle", and while Little Roy admits to being baffled initially by Nirvana's feedback-soaked grunge - "I was not in tune, because it is rock music, and I am not a rock fan" - he says he found something in the melody and lyrics that struck a chord: "These things Kurt Cobain wrote, they are the reality to him. That is the best writing that a writer could do. Many people experience the same things, that happiness and that pain. These songs are the experience of millions."

Nevermind, Nirvana's commercial breakthrough, celebrates its 20th anniversary this month with two releases: a two- and a five-CD set, due out on Monday. While the band customarily charts high in best-album-ever lists, it is important to remember that nobody saw it coming. Grunge, a blend of punk and heavy metal, had been percolating in the Seattle area since the mid-1980s - but it was fellow Sub Pop groups like Mudhoney and Tad, not the young Nirvana, who were most fancied for crossover success. And nor was this an obvious oversight. Nirvana's 1991 LP, Bleach, sold steadily - but apart from the lithe, tuneful About a Girl, their debut was a sludgy, depressive listen with little to suggest a group hoping to crack the mainstream.

The ambitious Cobain, though, was working on new, poppier songs, and when a clutch of demos recorded with the producer Butch Vig at Wisconsin's Smart Studios piqued the interest of major labels, he and bassist Krist Novoselic gave the drummer Chan Channing his marching orders, recruited a hard-hitting young Washington DC stickman named Dave Grohl, and signed a deal with David Geffen's DCG Records.

Geffen, hoping for a modest alternative hit along the lines of Sonic Youth's Goo, pressed up 250,000 copies. By Christmas 1991, Nevermind was selling 400,000 copies a week. In January 1992, it knocked Michael Jackson's Dangerous off the top of the Billboard Chart.

Nevermind touched a nerve. It was one of those records that made everything else look old, fake, out-of-touch. Cobain, undoubtedly, was of a different breed from the popular rock stars of the day - the Axl Roses, the Nikki Sixes. He was a very 1990s musician - obsessed with integrity, revolted by greed, but also artistically and commercially ambitious. His lyrics - Smells Like Teen Spirit, an ironic call to revolution, where "it's fun to lose and to pretend"; Drain You, a jaundiced vision of love as a laboratory experiment - were equal parts passion and cynicism, sardonic and self-lacerating.

As Scott Creney, writing on Brisbane's Collapse Board, puts it: "The voice in Nevermind is cruel, funny, tender, frightened, filled with rage, brilliantly insightful, totally stupid, self-indulgent, yearning, and inscrutable. Or to put it more simply, it's the voice of an adolescent."

If Nevermind precipitated a generational shift, it was because it spoke to its audience, not down to them.

It would be remiss to ignore the importance of Vig's production for Nirvana's success, though. This was no punk-rock record. Featuring multi-tracked vocals and overdubs, with additional snare samples added by the mixer, Andy Wallace, Nevermind punched out of the speaker. Members of the band were concerned it was too commercial, Cobain suggesting that it sounded "closer to a Mötley Crüe record" than a punk record. But its mix of cleanness and distortion, gloss and feedback came to characterise the way rock music was produced and mixed. In Nirvana's wake, angst became a saleable commodity, and groups such as Bush, Silverchair, Stone Temple Pilots - even, arguably, Nirvana's former drummer Dave Grohl, in his new band the Foo Fighters - made the sound into something packaged and commercial. Alternative rock joined the mainstream.

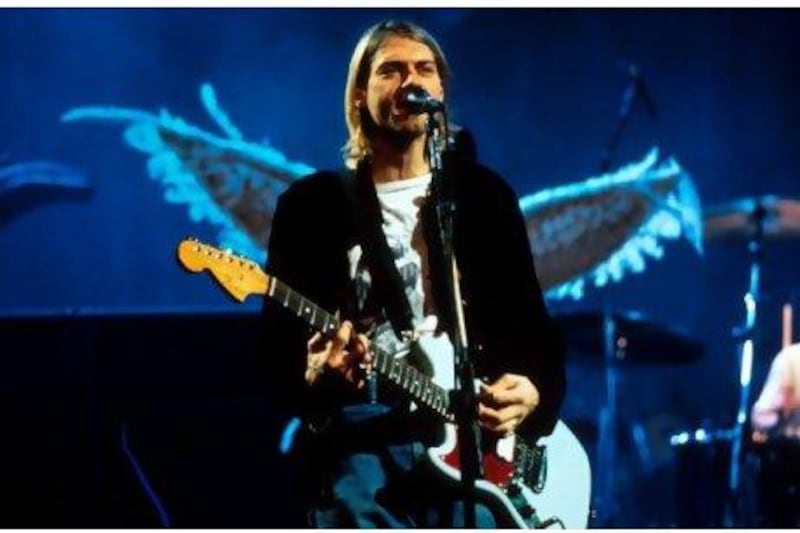

Since then, Cobain has become an iconic figure in the musical pantheon, a sort of Dr Faustus figure for the indie-rock age: the punk kid who sold his soul to the corporate rock devil, and got more than he bargained for. Twenty years on, Little Roy can remake teenage angst as roots reggae, and Dappy, rapper of UK chart-rap group N-Dubz, can rhyme: "You know I feel your pain 'cos I dun been through it/I'm Kurt Cobain but I just couldn't do it."

Back at Reading Festival, and as night falls, festival-goers gather at the stage, not to see a band, but a recorded performance - of Nirvana's Reading Festival show 19 years ago, in 1992.

Teenage angst might be all grown up now, but it's not going out of fashion.