The Democratic Republic of Congo's best bands are renowned for using home-made instruments cobbled together from junk. If that doesn't say much for the state of the country, it does at least testify to the ingenuity of its musicians. Take Sobanza Mimanisa, with their makeshift drums, and the disabled players of Staff Benda Bilili, who live in the grounds of Kinshasa Zoo, ride customised tricycles and use a tin can with a wire tied on to it as a lead instrument. Most famous is Konono No 1, Mawangu Mingiedi's likembé ensemble, who use microphones made from car alternators and scrap-metal percussion and amplifiers that look like they were built by Mad Max. Their sound is every bit as rough and vigorous as you would expect.

The likembé, also known as the thumb piano, comprises a series of tuned metal strips that are twanged against a resonator board to produce a dull plinking tone. Konono No 1 amplify and distort that note through what sounds like - and quite possibly is - a PA system. A trio of likembé players build up layers of cycling arpeggios: skipping, curiously off-key melodies that ride on top of an avalanche of frantic percussion and call-and-response vocals. The group's first record for Crammed Discs, 2004's Congotronics, caused a stir far beyond the ordinary world music circles, picking up fans in the gloomy redoubts of glitchy electronica, noise and industrial music. I first heard about them in a review of the Power Electronics outfit Whitehouse, a group that recites obscene poetry over a digital approximation of the dentist's drill. Papa Wemba or King Sunny Adé wouldn't look at home in that company but Konono No 1 did. Theirs was a dense, difficult sound, thrilling in short bursts but exhausting over the course of an album.

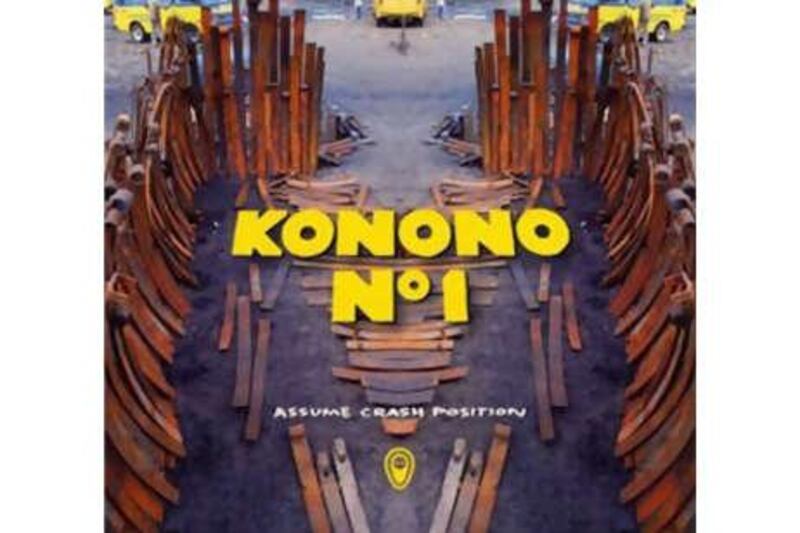

From its title, Assume Crash Position sounds like it ought to be more forbidding still. Instead, the group has expanded its palette with guitar and bass, creating a more conventionally poppy context for their still fascinatingly alien approach. It might not endear them to the Wire magazine subscribers who warmed to their previous record, but it ought to secure them a much broader audience. Their exuberance is channelled into much greater melodic and dynamic variety. The onslaught of bells and whistles occasionally subsides, letting ambient noises and the shouts of children seep through. The whole record has an infectious carnival spirit, but that isn't all it has. Parts of it are actively pretty - for instance the syncopated chords that float behind the likembé on the opening track Wumbanzanga. They might be a synth or some sort of brass section, or perhaps a steel drum, but they give the song a peculiar warmth and sweetness in spite of its hectic bass and oblique vocal lines. The phasing effects on Mama Na Bana call to mind the Japanese psychedelic group OOIOO, experts at taking the listener on a voyage through inner space that leaves you feeling fresher than when you set out. The record ends with a Nakobala Lisusu Te, a melancholy solo performance in which the full strangeness of the Zomba musical tradition becomes clear. It's tuneless, haphazard, rhythmically ungraspable and deeply intriguing. Even in their most broken-down moments, they know how to turn trash into gold.