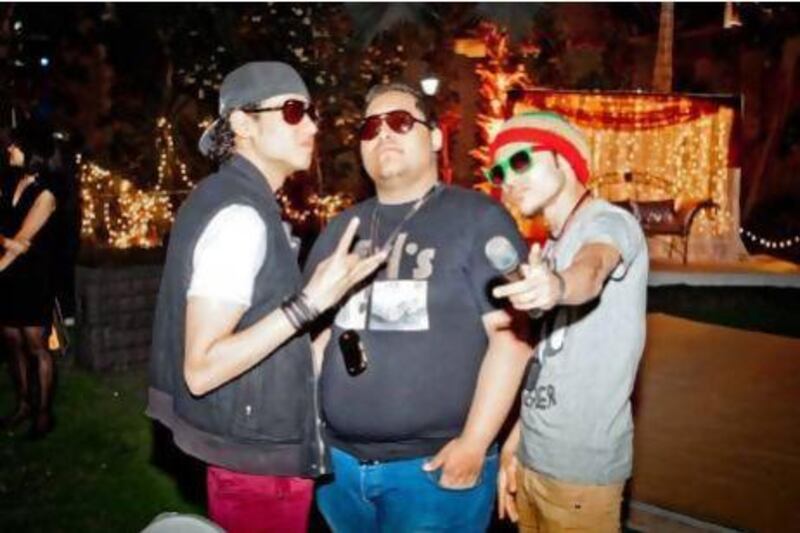

Earlier this month, DJ Amr Haha performed to a packed crowd at the Greek Club, a bar popular with Egypt's activists, foreigners and artists. Hundreds of upper middle class youth danced as Haha launched into a track that mixed a reggae line with traditional tabla drum beats. Speedy, shrill auto-tuned vocals spout evocative and vulgar lyrics, while Alaa Fifty Cent and Sadat - decked out in hip-hop attire and dreadlocks - act as what they call mic men.

Before the revolution, these performers would have likely been turned away at the door of this bar that had once been an exclusive meeting place for Cairo's Greek population. Now, they are the headline act at a private party as well as playing a weekly gig at After Eight, one of downtown's most upscale clubs.

Haha, Alaa Fifty Cent and Sadat El Alamy go by the name No Comment. The Greek Club feels far from where they typically play: on makeshift stages to huge crowds in the backstreets of Cairo's working-class neighbourhoods.

Known as mahraganat or festival music, the 23-year-old Haha's raw, high-energy tracks incorporate hip-hop, electronica and Egyptian shaabi, a term that means "popular" and is the music played at street festivals and weddings in lower-class Egyptian neighbourhoods. Full of heavy beats, high energy and wordplay, these tracks delve into the socioeconomic issues of daily life for the near 40 per cent of Egyptians who live below the poverty line. They are about drug abuse and government neglect. The dialect is heavy with slang, the lyrics are lewd and filled with expletives.

"I'm talking in the Arabic of the street, there's no proper singer who would go, 'Wake up, dude', but this language is the heart of Egypt and Egypt has a lot of shaabi places," says Alaa Fifty Cent, who grew up in the poor districts of Al Salam with the rest of Haha's crew.

The double entendres and wit of Haha's songs are apparent. Even as he's championing a cause, he takes a moment to lampoon it, such as in the pro-revolution song The People Want Five Pounds Phone Credit, which gives his support to Tahrir Square while poking fun at the ideology. Criticised as obscene, Haha's raw tracks are a sharp contrast to the lovestruck ballads of Arab pop stars that are irrelevant to Egyptians' daily lives.

"We try to criticise what's going on in the street, and it's simple enough to reach everyone," says Haha. "We aren't talking crap, we're talking about things that happen around us every day."

Shaabi music emerged from the poor districts of Cairo in the 1960s and 1970s and has been largely scorned by the country's elite. But in the aftermath of the revolution the young generation of shaabi artists have found themselves making the leap across the social barriers that they themselves rap about.

Haha began four years ago, with no training and little more than a cheap laptop and headset. The songs spread quickly, downloaded from the internet through social media and YouTube, and swapped on USB sticks and via mobile phones. Now Haha and other mahraganat artists are blaring constantly from the microbuses coming from Cairo's periphery and on the party boats that cruise the Nile.

In the past year, the music has been co-opted by Egypt's activist and upper middle class youth. According to Mina Girgis, a music ethnologist, electro shaabi represents one of the first times these rich, largely Westernised youths are able to find common ground with those outside their class.

"The music is really exciting and expressive, and people feel like it's a nuanced social solidarity," says Girgis, adding: "But it's still embryonic and will grow and change tremendously."

For Youssef Altwan, who has been researching mahraganat music for the documentary Underground/On the Surface, the breakdown in class barriers during last year's revolution helped spur the rising popularity of the genre. For the first time, Cairo's wealthy youth looked outside their ranks for a voice that represented their frustration and fears. They found it in electro shaabi's evocative, coarse lyrics. But Altwan admits that although the tracks are political, the songs aren't made for that purpose.

"The songs talk about issues, but the main thing for these guys, really, is to get the party started," he says.

And for these mahraganat DJs, the party is just beginning. Mobinil featured popular shaabi hip-hop DJs Okka and Ortega's track in a commercial this Ramadan (the Holy Month is the largest advertising period of the year in Egypt). Altwan, along with the filmmaker Salma El Tarzi, is set to release a documentary in early 2013 tracking the rise of Okka, Wezza and Ortega, a mahraganat team from the Cairo suburbs of Matareya.

While artists like Haha continue to build on the traditional genre, the mass popularity raises new questions about the future of Egyptian music.

"A lot of people are criticising it, asking, 'Is this music going to erase our cultural heritage?'" says Girgis. "If this is the soundtrack of tomorrow, what is it all about?"