It’s a cold, wet Sunday afternoon in London and several thousand people are packed into Old Billingsgate, a cavernous former fish market on the banks of the River Thames. It may sound grim, but in recent years this venue has been palatially renovated and right now it’s the next best thing to being in Brazil. Since its foundation in 2009, Back2Black – a three-day event dedicated to exploring the nexus of contemporary Brazilian and African music – has gained an enviable reputation in its hometown of Rio de Janeiro, presenting an impeccable selection of artists and playing host to a variety of unique collaborations.

Including performances by Femi Kuti, Sany Pitbull, Mulatu Astatke, Roots Manuva and many more, the festival's first trip to British shores has been equally exciting. However, nestled in the middle of the final day's bill, among sets by Back2Black's curator Gilberto Gil, the Brazilian singer-songwriter Jorge Ben Jor and the husband and wife duo Amadou & Mariam, is one particular highlight. Toumani Diabaté is the undisputed king of the kora – an entrancing 21-string calabash harp common in Malian music. Hailing from a family of griots (traditional West African historians, storytellers and musicians) that stretches back more than 70 generations, it is no exaggeration to say that he was born into

greatness.

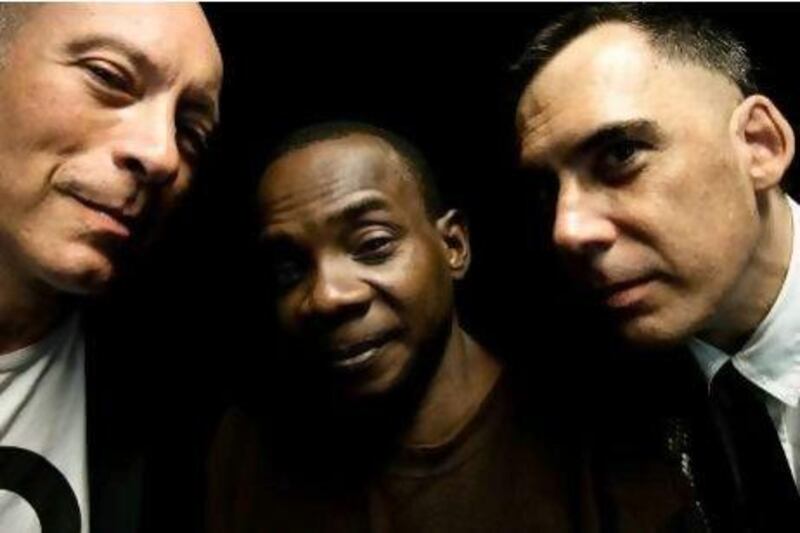

Tonight is no regular solo show, though. Diabaté is performing a set of tracks from his latest album, a collaboration with the Brazilian guitarist Edgard Scandurra and the poet-singer Arnaldo Antunes. Titled A Curva Da Cintura, its contents are an exercise in playful, organic fusion, blending folksy Latin pop and straight-ahead rock with traditional West African melodies. In contrast to the virtuosic intricacy of the rest of Diabaté's back catalogue, many of its 18 tracks sound rough-hewn and slightly unfinished. But that's all part of the charm. From the jaunty stomp of Meu Cabelo to the Portuguese vocal rework of Diabaté's Kaira, the project feels less like a polished studio recording and more like sitting in on an intimate jam between three extremely gifted friends.

For this performance, however, the three men opt for a rockier interpretation of the material. Antunes struts across the stage drawling lyrics with studied intensity. Meanwhile, Scandurra chops out powerful riffs that anchor a series of blistering workouts by Diabaté. Frequently accompanied by his son, Sidiki, who has inevitably entered the family profession and often joins his father on tour, he looks like a man in his element. Perhaps that has something to do with the fact that this is, in its own way, a sort of homecoming.

As Antunes explains backstage, the idea for A Curva Da Cintura began to take shape at the 2010 edition of Back2Black in Rio. "Myself and Edgard were invited to do a concert with Toumani two years ago," he says. "The rehearsal was the very first time we had ever met, but when we started to play together [there was] a magical synergy between us. At the end, Toumani said: 'We need to make a record together – you need to come to Mali.' Edgar and I already had a plan to work together anyway, so we thought, 'Why not ... we can just include Toumani in that project, too.' Soon after we made that decision we were all in Bamako making the album."

Given the obvious ease of both their professional and personal relationships, it comes as a surprise to learn how little these men knew about each other before that first meeting. Propping his crutch against a wall (a childhood illness left him with a paralysed leg), Diabaté sits down and casually admits: “I had never even heard [Scandurra and Antunes’] music. We had only two hours to rehearse the day before we went on stage together. When you love what you are doing you tend to have an open heart and an open mind, so making those connections with other people can sometimes be very easy.”

This idea of making connections is a thread that runs through Diabaté's work. Proudly steeped in centuries of Malian tradition, he has also spent much of his career reaching out to the rest of the world. He has played the kora for 41 of his 46 years and in that time has arguably done more than any other artist to bring Malian music to a global audience. Accordingly, he is a seasoned collaborator, notching up projects with fellow countrymen such as the late guitar master Ali Farka Touré (2005's Grammy-winning Heart of the Moon) and international names including Taj Mahal (Kulanjan, 1999), Damon Albarn (Mali Music, 2002) and Bjork (Volta, 2007). "All those projects were different," Diabaté explains. "Every collaboration has its own feeling, but they all have a very strong connection in spirit: peace, communication, love and the idea of bringing people together. It is very simple. For this project when [Scandurra and Antunes] visited Mali, they came to meet my family, ate with us and then we just made music together. The official language in Mali is French and in Brazil it's Portuguese, so we couldn't talk much. But that didn't matter. We spoke to each other with music."

The idea of music as a common language is hardly revolutionary, but Diabaté’s words are especially pertinent in relation to this particular project. From 1500 to 1815 the Portuguese Empire transported more than three and a half million slaves to Brazil. Forced to work in mines and on sugar plantations, this uprooted population powered the colony’s economy. It also rewired the culture of the whole nation. Now, from samba and maracatu to funk carioca, Africa’s pulse beats through every style of Brazilian music.

This fact has long been recognised by artists such as Gilberto Gil, a singer and guitarist who made his name as a pioneer of tropicália: an experimental artistic movement based on a theory of subversive cultural eclecticism originally outlined by the poet Oswald de Andrade. In 1928, Andrade wrote a short text asserting that Brazil’s greatest weapon in the battle against post-colonial European dominance was antropofagia, its ability to “cannibalise” diverse influences into “one participating consciousness”.

Some years later Gil and a like-minded group of friends, including Caetano Veloso, Tom Zé, Nara Leão, Os Mutantes and Gal Costa, set about translating this idea into sound. The result was the 1968 album Tropicália: ou Panis et Circencis. Crashing traditional styles headlong into psychedelic rock and pop, it marked a turning point in the history of Brazilian music – and the lives of its makers. Shortly after its release, both Gil And Veloso were forced into a three-year exile in London owing to the album’s fierce criticism of the Brazilian coup d’état of 1964 and the military government it brought to power.

In subsequent years Gil’s work has absorbed and interpreted elements of everything from folk, jazz and punk through to soul, Afrobeat and reggae. He has hung out and performed with Fela Kuti, Stevie Wonder and the Incredible String Band and, in the process, recorded more than 50 albums. Now, at the age of 70, he has made a successful transition from radical activist to elder statesman, serving as the Brazilian minister of culture from 2003 to 2008. Such credentials make him the ideal man to helm an event such as Back2Black.

“The spirit of this festival is to follow a multicultural and intercultural approach to music and art and to promote fusion and dialogue between different nations,” he explains during an early morning photoshoot. “That’s why I am very proud to have a project like [A Curva Da Cintura] being performed here.

“For centuries there has been a natural historical link between African and Brazilian music. African people and culture are at the heart of modern Brazilian civilisation. Africa is part of our soul, part of our DNA and this relationship is something that we should all celebrate.”

Another aim of the festival is to showcase the power of art to inspire and empower ordinary people. To this end the daytime schedules are filled with workshops and panels. The best of these is Music in Exile, a discussion in which Gil and the legendary South African trumpeter Hugh Masekela relive the years they spent banished from their homes by repressive governments in the late 1960s and 1970s. Filled with forthright opinions on the responsibility of public figures to protest against injustice and an equal amount of laughs, it proves that pop and politics do and should mix.

Though Diabaté’s approach is less overtly politicised than Gil’s, he is, as ever, perfectly in tune with everything around him. Just before we end our conversation I ask about his extraordinary heritage and how he reconciles it with experimental projects such as A Curva Cintura. He chooses not to talk about the past and, instead, outlines how important it is to keep tradition alive and of the present.

“Everywhere people are talking about the economic problems and other crises around the world,” he says. “But people are forgetting about culture and art – and these are the things that can give everyone a voice.

“It’s important to have a strong and developing culture and to bring different people together. Through that we learn to understand ourselves and each other. The more we can do that, the more able we will be to fight our problems together.”

Back2Black Rio will be held at Leopoldina Station Rio de Janeiro from November 23rd-25th. For more information, visit back2blackfestival.com.br.

Dave Stelfox is a journalist and photographer based in London. His work has appeared in The Guardian, The Independent and the Daily Telegraph.