There might have been more than a touch of bravado when then-aspiring music mogul Berry Gordy dubbed his new Detroit home "Hitsville, USA" – but the sign he hung outside soon after the 1959 purchase would feel like a quaint understatement a decade later. By the end of the 1960s, Gordy's Motown hit machine had clocked an incredible 79 Billboard Top 10 singles, spawning a generation's soundtrack – while launching the careers of icons including Michael Jackson, Diana Ross and Stevie Wonder – and presaging a landmark era of racially integrated entertainment, affording African-American performers mainstream success hitherto unimaginable.

Among the last of these golden-era smashes was Marvin Gaye's I Heard it Through the Grapevine – that classic jilted lover's refrain turned a stately 50 years old on Tuesday. Following its 1968 release, the track would become the label's then-bestselling single, sitting pretty at the top of the US charts for seven weeks. And it has unmistakably stood the test of time – few songs from the Tamla-Motown stable have endured in the public imagination quite so endearingly, nor attracted as many covers, references and lifts.

The word classic feels inadequate to sum up ...Grapevine's smarts, charms or legacy – it's a song which at once cool and groovy; impassioned but restrained; proud yet self-pitying. Like the best of Motown, it feels both familiar and otherworldly, simple yet unmistakable, a crystalline harmony of three essential ingredients – the song, the sound, and the singer.

It's a well-worn anorak's anecdote that Gordy initially rejected Gaye's performance – a fact that says as much about the mogul's meticulous standards as his hit-spotting skills. What it reminds us is that ...Grapevine was already a hit – a year earlier, Gladys Knight & the Pips reached No 2 on the Billboard charts, with a funkier, poppier version of the same song, which also cropped up on Smokey Robinson & the Miracles' Special Occasion LP in August 1968.

That ...Grapevine was already road-worn by the time Gaye got his bite highlights a revealing part of the Motown story. Songs weren't owned by anyone, and the songwriter definitely outranked the singer.

Enter – and exit – legendary songwriting/production team Holland-Dozier-Holland, who would pen a total of 27 Top 10 hits for Motown artists between 1963 and 1967; including Baby Love, I Hear a Symphony and seven other No 1s for The Supremes (then fronted by Diana Ross), and many of Gaye's earlier singles, such as Can I Get a Witness and How Sweet It Is (To Be Loved by You).

The dream team of Lamont Dozier and brothers Brian and Eddie Holland can be credited with much of the success of the Tamla-Motown roster, but by early 1968, they had left the label over pay disputes with Gordy. That opened the floor to their greatest in-house rival, Norman Whitfield, who had already authored Gaye's breakout single Pride and Joy in 1963, and he leapt on the gaping hole left by the "HDH" team's departure. He quickly wrestled control of The Temptations, helping author the psychedelic soul sub-genre of the late-1960s, via trippy tracks Cloud Nine and Papa Was a Rollin' Stone.

But Whitfield would never strike a brighter shade of gold than I Heard it Through the Grapevine, penned alongside frequent collaborator Barrett Strong – a full-circle looping back to Strong being the voice behind Motown's first hit, Money (That's What I Want), later covered on The Beatles' second LP With the Beatles.

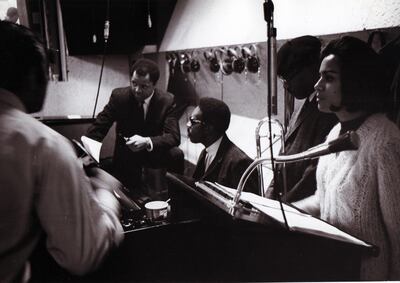

But arguably just as important as these seminal songwriters are the musicians who brought them to life. Camped out in a tiny basement at that famed suburban home, 2648 West Grand Boulevard, Detroit – Gordy would later purchase seven surrounding properties – Motown employed a tight roster of razor-sharp session players, on call 22 hours a day, who would record nearly all the label's productions. Known as The Funk Brothers, it's estimated that this core of barely a dozen musicians played on "more No 1 records than The Beatles, Elvis, The Rolling Stones and The Beach Boys combined" – or so claims celebratory 2002 reunion documentary Standing in the Shadows of Motown.

The proximity was key. This combination of a steady, workmanlike group of in-house songwriters, working alongside a brotherly collective of slick pro musicians – all of whom reported directly to Gordy – gave birth to a uniform sound as unmistakable as it is unreplicable. The fabled “Motown Sound” is simple on the surface, but disguises subtle sophistication: melodies are big, catchy and clever, but packaged in tight, predictable song structures ensuring regular repetition and maximum “hummability”, while gospel-inspired call and response vocals intuitively compel the listener to engage and respond. Everything sounds bigger than it is – in part credited to Motown’s then-uncommon practice of multitracking identical instrumental parts.

Carefully sculpted to thrust out of the primitive AM radios of the day, today, the audio mix often sounds primitive and tinny: horn parts blare shrilly, while syrupy strings appear to float a mile above the groove. A Motown trademark is that crudely prominent tambourine accentuating the steady plod of an already danceable backbeat. But this sonic separation was integral in disseminating these earworms on to the airwaves; basslines are especially bright and high in the mix, a forbearer of the funkier sounds to come. And, crucially, it swings – but it's never loose. The Funk Brothers' jazzy chops lend the music a rhythmic erudition, but ultimately, nothing is allowed to overpower the melody.

All that's left to make a hit song, then, is the singer – and there are deserved volumes written extolling the disparate talents and approaches of Gaye, Wonder and Robinson; of Knight, Martha Reeves and Tammi Terrell; of The Temptations, The Supremes and The Jackson 5. But the thing they all have in common is appealing to the ears – and business sense – of Gordy, who personally signed all the label's heyday-era acts and held an auteur's grip over the whole operation (only selling his controlling stake in 1988).

One of the most successful music moguls of all time, Gordy has amassed a reported fortune of US$345 million (Dh1.27 billion), and developed a ruthless streak to match – his numerous cut-throat decisions include shutting down the original Hitsville and moving to Los Angeles in 1972, the moment many say the music died. Among his loudest detractors was the film Dreamgirls, a loosely fictionalised account of The Supremes which portraits a morally bankrupt music executive that Gordy has sought to distance himself from. Whatever the truth, when parking the study of ethics in favour of aesthetics, Gordy's contribution to popular music is beyond dispute.

____________________________

Read more:

From Jimmy Cliff to Desmond Dekker: inside reggae’s Trojan Records

Tunes of terror: music that will give you the heebie-jeebies

Dua Lipa to headline Louvre Abu Dhabi's one year anniversary celebrations

Seven of the world's top DJs to perform in Dubai during November

____________________________