When Bob Dylan really wants to get your attention he doesn't shout, he mumbles. You can hear him using the tactic in 1966, to the restless Manchester crowd that called him "Judas". He murmurs something inaudible; they quickly shut up and listen, before he blasts them again with his new electric music. In 1997, Dylan successfully reprised the strategy for listeners to his new album, Time Out Of Mind. On a song called It's Not Dark Yet, the narrator matter-of-factly listed his life's achievements (estrangement, hardship, a "soul turned to steel"), before reflecting on mortality and passing time: "It's not dark yet but it's getting there." With the song, Dylan helped observers usher in the "late" period of his career. Since then, you've been able to hear a pin drop in here.

And, much as he did in 1966, now that we're paying attention, for the last decade Dylan has taken the opportunity to blast his listeners with some of the most engaged, vibrant and, at times, plain ribald music he's made in 30 years. In his last three albums he's made good jokes, atomised the decline in American manufacturing and co-opted characters from Shakespearean tragedy. He's sampled fleshly delights, referenced Alicia Keys and James Joyce and toyed with Dylan scholars: dropping what sounds a lot like winking self-reference into his songs. In I Feel A Change Comin' On (from 2009's Together Through Life) he addresses his croaking vocals: "Some people tell me," he gasps, "I've got the blood of the land in my voice."

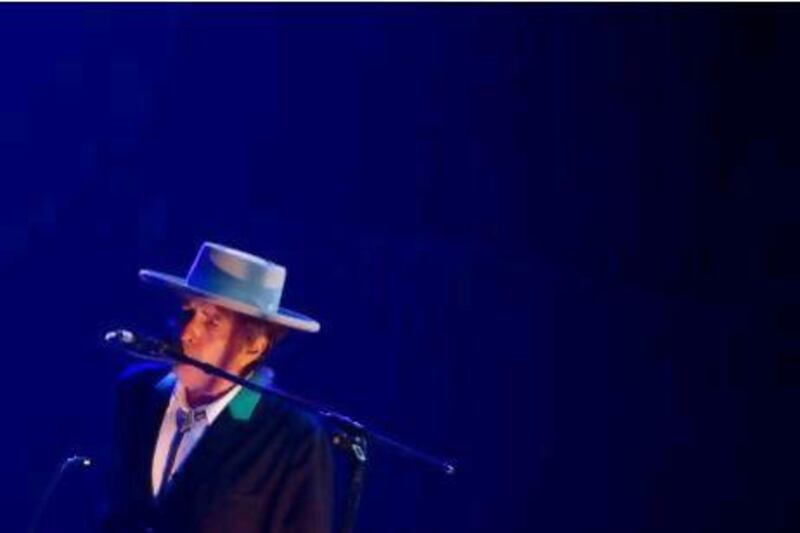

This he's done in the company of his road band, the kind of characters you'd only meet otherwise in a Quentin Tarantino movie: well-tailored men with undiscussed histories and an enigmatic professionalism. Augmented by multi-instrumentalist David Hidalgo from Los Lobos, the band have lately helped him create some of his earthiest rock 'n' roll (and pre-rock 'n' roll) music. Its peak to date has been the magnificent Together Through Life, in which Dylan's naturalistic sound (since 2001 he has produced his own albums, under the pseudonym Jack Frost) caught his songs as they might have been delivered in a swinging roadhouse bar or sun-bleached cantina in some imagined 1961.

As Duquesne Whistle, the first song on Tempest, is heard in the distance, it's clear that this is not destined to be an album that faithfully captures the sound of guys in suits playing in a room with Bob Dylan. Instead, the song creeps over the horizon and suddenly booms into life. The album is still earthy, but it's earthy in a far more dramatic kind of a way. Its subject matter is Old Testament, but it's a cinematic, Cecil B DeMille Old Testament, where you're impressed by the scale of the drama as much as the grittiness of the content.

Duquesne Whistle is the "single" but, as the album moves on, hindsight proves it to be a pretty unrepresentative one. The second song, Soon After Midnight subtly begins to undermine the innocent mood. It begins with a muted guitar arpeggio that effortlessly evokes the rock 'n' roll of Dylan's own youth: impossible to hear without picturing the light from a glitterball playing over a couple dancing in a high school gymnasium.

Subtly, though, Dylan begins to cast a shadow into the song. Come the bridge, the narrator has turned plain sinister, wreaking revenge on anyone who would tarnish the idyllic innocence of young love: "Two-timing Slim, whoever heard of him?/I'll drag his corpse through the mud ..." If we've met characters like this in Dylan's recent work, here's their more sinister cousin.

As Tempest proceeds, in fact, you admire the songs, are bowled over by the vision for the production but must also acknowledge the number of bodies piling up around the place. It was apparently Dylan's intention to write an album of explicitly "religious" songs, but that idea clearly didn't pan out. Instead Tempest has a lot to say about violence and about death. Not mortality, you understand. This isn't a series of mature meditations - this is a drama showing you deaths good, bad and ambiguous.

Narrow Way is a jaunty electric blues that explores life's toughness with such a rigour, it stops the song short of swinging the way it would have done if it had appeared on Together Through Life or, Bringing It All Back Home.

It's a menacing message: "I'm armed to the hilt," Dylan snarls, "and I'm staring hard/You won't get out of here unscarred ..." The song's hookline, meanwhile, seems to point to some ultimate reckoning, or major financial readjustment: "If I can't work up to you/You'll surely have to work down to me someday ..."

Its character is violent but Tempest is still a record of changeable moods. At times, as on Scarlet Town (in a nutshell: keep driving) and Tin Angel (a longform murder ballad with no survivors), the management of the material recalls the piratical minstrelsy of Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds. On two songs earlier in the album, Long And Wasted Years (a talking love song, with more words than space to put them) and particularly Pay In Blood (a swaggering rock song), the music recalls that of the mid-1980s Rolling Stones - a point at which the band's internal friction manifested itself in rock music of considerable animosity.

Those craving the organic, sweaty live room playing of Together Through Life, meanwhile, are rewarded with a savage electric blues track called Early Roman Kings. The familiarity of the mode and the tune (the band are vamping on Muddy Waters' Manish Boy riff) might seem throwaway, but in the song Dylan commences an impressionistic attack on modern speculation, greed and ostentation: "The peddlers and the meddlers/They buy and they sell/They've destroyed your city/They'll destroy you as well ..." Who, then, is the larger-than-life character who can face down these philistines?

That will be Bob Dylan. Swaggering like an elderly but virile bluesman, he appears. "I ain't dead yet," he howls. "My bell still rings ..." He has come to bring a terrible vengeance, part-moral, part-musical. "I'll strip you of life/Strip you of breath," he avows. "Ship you down/To the house of death ..." He then sets to work: "Bring me my fiddle/Tune up my strings/Gonna break it wide open/Like the early Roman kings ..." It's the late Bob Dylan character in his full pomp: playful, witty, with the authority of his history behind him, but with a lot of lead remaining in his pencil. In times like these, he's saying, it's someone like me you want on your side.

Tempest ends with Roll On John, a slightly sentimental salute to Dylan's friend John Lennon, that at one point rather fancifully imagines Lennon as a hunted outcast hiding in a cave.

The intended impression appears to be that Lennon, although murdered, was such a cosmic spirit he should not be seen as someone who died but, rather, someone who was freed from the chains of life. It's an idea quite at odds with the preceding song, the album's title track: a 14-minute ballad about the sinking of the Titanic, in which death is unmysteriously very much the end.

Cutting between passenger vignettes (we meet family man Mr Esther; Wellington, some kind of wealthy villain; Davy, a brothel keeper) and reports of the ship's inexorable journey to disaster, Tempest is a consummate piece of narrative songwriting, with Leo DiCaprio along for the ride. For Dylan, the ship is the SS Societal Analogy - a reminder that although we are of unequal station in life, we will all be very much in the same boat when we're dead. "Sixteen hundred had gone to rest," Dylan sings, as he wraps up his report on the disaster, "the good, the bad, the rich, the poor, the loveliest and the best."

It's not a warming message. But for all the horror we've been shown in this album, it's clear that Tempest, from the optimists awaiting the arrival of the Duquesne train at its start, to the fraternal bonds of Roll On John at the end, is an album that has the enduring, redemptive power of love on its mind.

If the one thing that we can be sure of in life is that it will end, then the tacit message of Tempest is that, in the short time that we're here, we need to seize all the opportunities we have for love. Essentially, that in the end, as John Lennon's band once put it, the love you take is equal to the love you make.

John Robinson is associate editor of Uncut and the Guardian Guide's rock critic. He lives in London.