“I changed music five or six times – what have you done?” Miles Davis famously crowed at a White House dinner late in his life. Never a man known for his modesty, for once the Prince of Darkness was selling himself short.

By our count, there are at least nine occasions on which the world’s most recognisable (and bestselling) jazz musician has played a pivotal role in changing the course of music for evermore.

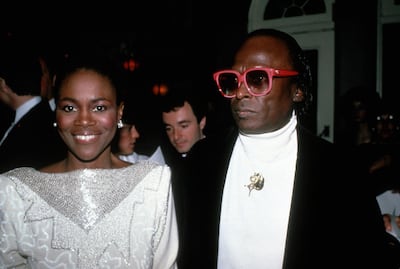

A major career-spanning documentary Miles Davis: Birth of the Cool is now on Netflix – a film that charts the musical pioneer's career and features previously unseen interviews with his friends, family, collaborators and admirers, including guitarist Carlos Santana. Its timely release isn't coincidental, either, and comes 50 years after Davis's most commercial period was about to begin. Let's take a walk through the history of post-war improvised music via the work of its most restless innovator.

Birthing ‘the cool’

In 1944, an 18-year-old Miles Davis left East St Louis to study music at New York’s prestigious Juilliard School. His real education, however, was in the clubs of 52nd Street, then booming with the frenetic, virtuosic, breakneck-tempo bebop of the time.

Within months, Davis was cutting his teeth as a member of troubled sax player Charlie Parker’s band, but in truth, the trumpeter’s own improvisational flights were never as sharp or showy as those of his contemporaries.

His answer was to slow tempos, bring in extra harmonies and horns, and alongside arranger Gil Evans, make a series of chilled, classically influenced nonet chamber recordings that would later be collected as the album Birth of the Cool – and credited with kick-starting the cool jazz wave to come.

Walkin' and hard-boppin'

Before the LP age, jazz records were typically bite-sized, few-minute snapshots often offering star soloists just a 32-bar cycle to blow and shine.

Taking cues from the bandstand workouts of the day, Davis let his players stretch out over the basic blues progression Walkin' (1954), which wound up at 13 minutes long, a showy swagger steeped in the groovy R&B and earthy gospel influences that came to characterise the hard-bop sound which would dominate the next decade of jazz – most especially on the music of era-defining Blue Note Records.

The third way of Miles Ahead

In 1955, Davis ascended from being a jazz star to a household name after signing with the mainstream might of Columbia Records.

He put this new influence – and budget – to good use, reviving his partnership with Evans to conceive Miles Ahead (1957), the first of three seminal albums that pit his breathy, tender trumpet exertions over the luscious textures of a 19-piece orchestra.

Followed by the Gershwin collection Porgy and Bess (1959) and flamenco-flavoured Sketches of Spain (1960), this trio collectively popularised the jazz-classical hybrid known as Third Stream.

Going modal with ‘Kind of Blue’

Davis severed himself from 50 years of harmonic jazz convention with the 1958 composition Milestones and, most famously, the ever-enduring, first-take-only sextet session of 1959 Kind of Blue, which is widely celebrated as the bestselling jazz album ever.

Davis' pioneering approach to composition freed players up to stretch out in a single tonality, in the same way trippy blues-rock musicians would play 10 years later. On the revelatory track Flamenco Sketches, soloists were presented a list of five modes to improvise in at leisure, the rhythm section following rather than dictating the harmony, shifting chord only when the soloist chose to move to a new tonality. Breathtaking.

Birth of the post-bop

Craving new ideas, in the mid-1960s, when he was in his mid-forties, Davis began assembling a new band of musicians half his age – including future stars Herbie Hancock and Wayne Shorter – who would collectively usher in a new democratic musical model known as post-bop, which would change jazz for ever.

Often using Shorter’s oblique compositions for fuel, the “Second Great Quintet” broke down the conventional soloist and rhythm section approach with a telepathic “time, no changes” philosophy that allowed song structures to unfold in real-time. The highest form of spontaneous musical expression.

That thing they called fusion

For all his earlier innovations in jazz, arguably none of Davis's skin-shedding stunts had a wider influence on pop culture than his early 1970s electric reinvention, heralded by the arrival of ... Brew – the undefinable improvisatory assault of an album that celebrates its 50th anniversary on Monday, March 30.

About seven months earlier, Davis assembled more than a dozen musicians – including two drummers, two bassists and three electric keyboardists – at Columbia’s New York studios, and over only three days, directed deep, dark, shamanic jams that conjured something entirely new and utterly beguiling.

Intoxicating to rock fans and festivals, once-slick-suited Davis was reborn as a scarf-toting counterculture hero, while the record’s principle players would go on to pack arenas playing that much-maligned marriage of jazz and rock that came to be known as fusion.

Getting funky ‘On the Corner’

James Brown invented funk in the mid-1960s. Sly Stone channelled Jimi Hendrix and helped birth funk-rock. Davis took note and wanted a piece of that lucrative, block-party-starting pie. The term "jazz-funk" would soon come to epitomise smooth, smoochy, noodly, blandness, that's no charge you can level at Davis' dense, groovy improvised On the Corner LP. It again featured Hancock, whose own subsequent 1970s recordings, beginning a year later with million-seller Head Hunters, would go on to define the genre more than anybody's.

Miles invented drum ’n’ bass. Kind of …

Sounds crazy, right? But there are semi-legitimate arguments and compelling corners of the internet that argue that the relentless, polyrhythmic wig-out Rated X laid the tracks for the genre to emerge across the pond two decades later. Just listen to the way backbeats and downbeats are reversed (or what translates as a bass drum and a snare), creating a squelching percussive tumult that overrode discernible melody in a way that biographer John Szwed calls the birth of "ambient jazz". It's not even the weirdest moment on Get Up with It (1974), a two-hour opus of unnerving offcuts that contained Davis's final studio recordings before a six-year hiatus.

Are you calling Davis ‘smooth’, for real?

After a lost half-decade of hedonism and health problems, Davis re-emerged in 1981 with another sonic reinvention awkwardly reconciling a 1980s pop aesthetic with some pretty deep jamming. A period that remains divisive to this day, things reached a peak, of sorts, with You're Under Arrest (1985), which included Davis's instrumental takes on Michael Jackson's Human Nature and Cyndi Lauper's Time After Time – which offered a sense of legitimacy to the smooth jazz that was to haunt US radio for decades to come.

Miles Davis: Birth of the Cool is on Netflix now

_______________

Read more:

[ Remembering Manu Dibango: what I learned from watching the African jazz legend soundcheck ]

[ From Bob Marley to Koffee: vibe out with our new #stayhome reggae playlist ]

_______________