Daniel Barenboim is no stranger to political controversy. The Argentine-born Israeli conductor has long been outspoken in his support for Palestine and condemnation of Israel. He was called a fascist by Israelis objecting to a performance with the Berlin Staatskapelle in Jerusalem during which he played the Tristan und Isolde overture by the anti-Semitic composer Richard Wagner. And earlier this year, parts of the Arab press, including Beirut's Hizbollah-affiliated Al Akhbar, called him a Zionist, agitating against his planned reprise of the Katara Festival for Music and Dialogue in Doha, which, indeed, was cancelled in April.

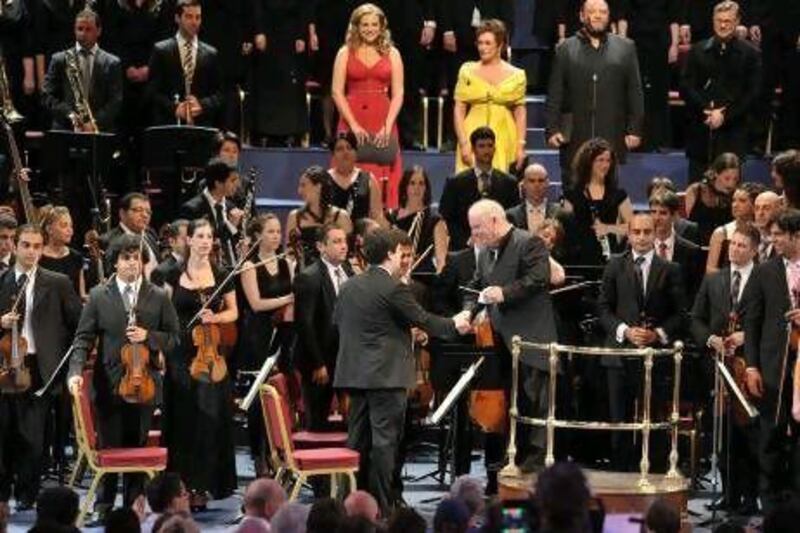

However, in 1999 he, and the late Palestinian-American scholar Edward W Said, founded the West-Eastern Divan Orchestra (Wedo) and the Barenboim Said Foundation, both of which intend to bring Arab and Israeli musicians together, using the power of music to heal cultural and political rifts. Wedo has been seen as such a significant movement towards conciliation between the peoples of the Middle East that Barenboim has won numerous international awards and peace prizes for his work. He was the first Jewish-Israeli to be offered honorary Palestinian status and was chosen to be an Olympic flag bearer at London's Games, alongside the likes of Ban Ki-moon, Shami Chakrabarti and Muhammad Ali. Just a couple of hours before, he had led his orchestra in the final performance of the complete cycle of Beethoven symphonies at the BBC Proms: the Ninth Symphony, with its glorious final movement's Ode To Joy.

During the time that parts of the Middle East have been tearing apart and reassembling their societies, for better or worse, Barenboim and the members of Wedo, who hail from Palestine, Syria, Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon and, of course, Israel, have embarked on a vast, three-year Beethoven project, recording, touring and discussing the remarkable power of the composer's music to appeal to people all around the world, musically educated or otherwise. Their newest release, Beethoven for All: Music of Power, Passion & Beauty, picks out the best of the orchestra's recordings, as well as piano recordings performed by Barenboim himself and accompanied by the Berlin Staatskapelle, acting as an introduction to Beethoven - and, indeed, to classical music.

At more than 25 minutes, The choral finale from Beethoven's Ninth is the longest work on the double album, and it plays as a remarkably timely work for the continuing Arab Spring: Beethoven was reputedly inspired to write the work by the events of the French Revolution, and it was played at the fall of the Berlin Wall and by the students protesting at Tiananmen Square. The work's journey from dark, struggling beginnings to the triumphant unity of an entire choir and orchestra blasting out its message of joy seems to mirror the hopes of revolutionaries past and present. Barenboim echoed that fervour when, at the end of that final Proms performance, before setting off for Olympic Park, he unexpectedly returned to the podium to address the audience. "What makes this orchestra what it is, besides the individual talents and the musicianship and the hard work and the education of its members, is they play together with this homogeneity, because here in our little society of the West-Eastern Divan, they are all equals," he said. "We know perfectly well that we will not be able to change the Middle East but I can assure you we are not going to let the people who are now in power in the Middle East change us."

It's a political path that is fraught with difficulties, and while Barenboim and Said's widow Mariam, with whom he runs the Barenboim Said Foundation, insist that Wedo is not a political institution, they are unlikely to avoid being tarred with the partisan brush - particularly with Barenboim's outspoken nature. During his speech at the Proms, Barenboim explained that a concert in East Jerusalem had been cancelled because of Palestinian protests.

"We were going to go and play a concert in solidarity with ... Palestinian civic society in East Jerusalem, and there were Palestinian factions who protested about this concert and we're not going there," he said. "Never mind the concert. Much worse is the reason. The reasoning behind it is that we represent, for them, an instrument of normalisation - in other words, of accepting the present status quo of occupation, the settlements and all that that means. And I want to tell you one thing: we are not a political project; we don't have a political programme but we have a certain amount of social conscience and solidarity with civic societies who suffer. Outside of the music we have only one agenda and one hope for everybody and that is total justice for all the inhabitants of the region and equality of rights for everybody so that we can start thinking about how we can approach each other."

Even setting aside the orchestra's stated purposes, with a make-up of musicians from across the Middle East, the unrest cannot fail to have an effect on Wedo. Mariam Said, in a press conference at the Royal Albert Hall, acknowledged this. "Everything in the region does affect us one way or another ... it affects positively and negatively. This crisis actually, the Arab Spring, was positive because before that, in Egypt, there were restrictions on some musicians, and some of them had difficulties in joining the orchestra because the cultural boycott in Egypt was strong. The Arab Spring released that and Egyptians are appearing comfortable and coming forward to join the orchestra. At the same time the crisis in Syria has made it impossible for Syrian musicians to get out. They really can't leave."

Part of the orchestra's purpose is to provide a philosophical education to its members as much as a musical one. And when they gather each summer to rehearse, they also attend symposiums and talks from significant cultural figures such as Lebanon's Elias Khoury and the pro-Palestinian Israeli author David Grossman. Last year, Barenboim and Mariam Said focused these talks on the Arab Spring, inviting the panel to ask the musicians for their views.

"There was a musician who was asked by somebody in the panel what she thought of the revolution in Egypt, and she said she was torn because, on the one hand, she would like to say how wonderful it is, with democracy and people deciding for themselves; on the other hand, she was concerned about what it would do to the relationships between Egypt and Israel," said Barenboim at the Royal Albert Hall. He himself is vocally critical of Israel's reaction to the Arab Spring.

"It is obvious that the Arab revolutions have changed the way of thinking of the whole area," he said. "I thought it was a great shame - yet another missed opportunity by the Israeli government - not to salute that, as if Arab revolution in Egypt or the Arab Spring is concerned only with its relations with Israel. The word Israel is not mentioned: it is a revolution of people who decided to take their destinies in their hands and didn't want any more dictatorship. It can go wrong, we know that, but every time we start something new it may go wrong. But first of all you have to salute that, and especially Israel, that has been claiming for so many years that it is the only democracy in the Middle East. Well, what better opportunity? Missed yet again."

Listening to the orchestra, though, or seeing the work of the foundation's educational music projects in Ramallah and Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon, the results of Barenboim's belief in the power of music to obliterate the hatred engendered by political injustices is inspiring.

Beethoven said: "I despise the world which does not intuitively feel that music is a higher revelation than all wisdom and philosophy." It is likely, then, that the West-Eastern Divan Orchestra would have pleased him.

Gemma Champ is a freelance writer based in London.