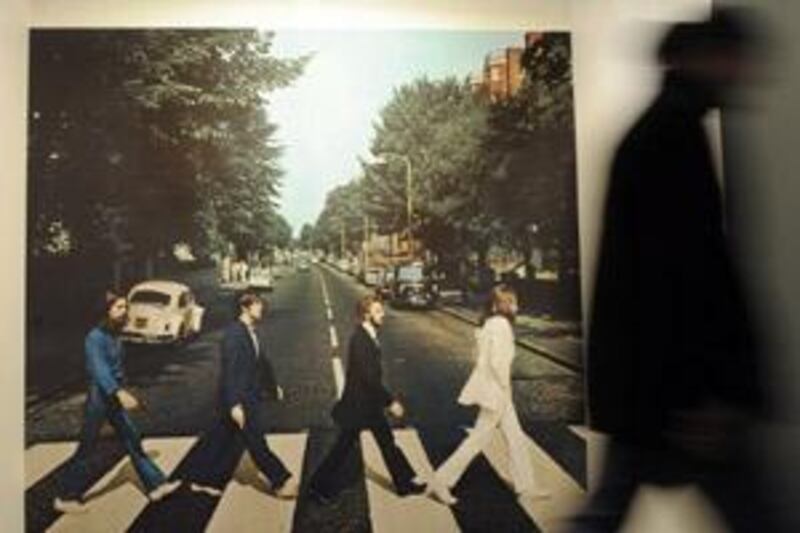

It is 1969. A teenager carefully removes a vinyl disc from its cardboard sheath. As he puts the needle on the record he stares at the cover of Abbey Road, which features a photo of four men strolling across a zebra crossing. Why is Paul McCartney barefoot and out of step with his band mates? What is the significance of the licence plate on the Volkswagen Beetle parked nearby? Who is the man in the background? What does it all mean?

The shoot for Abbey Road - 40 years ago this week, at 11.30am on August 8, 1969 - took 10 minutes to complete. McCartney had given the Sunday Times photographer Iain MacMillan a sketch of how he wanted the picture to look. All MacMillan had to do was climb a stepladder in the middle of the road and take six photographs of The Beatles crossing the street while a policeman kept an eye out for over-exuberant fans. In the end, they went with the fifth picture and a legend was born.

The Beatles' 11th official album, released in September 1969, features what has become one of the most discussed covers in pop history. Other covers may be better - Andy Warhol's cover for The Rolling Stones' Sticky Fingers or Vaughan Oliver's work for The Pixies, for instance - but none has been pored over with the same level of scrutiny. "The album covers that survive have some kind of mystery attached," says Danny Eccleston, the executive editor of Mojo magazine. "They pull you in. Abbey Road does that perfectly. Abbey Road has that Renaissance perspective - everything is stealing back to a point where all the lines converge, so it pulls you in and you inhabit the sleeve as you look at it."

The album sparked a rumour that the barefooted McCartney was dead and that the characters "28 If" on the licence plate of the VW Beetle seen in the background referred to the age he would be if he were still alive. MacMillan debunked this notion when he later explained they'd asked the police to tow the car minutes before the shoot began but the police could not. Today, the same Beetle can be found in the Volkswagen museum in Wolfsburg, Germany. Why McCartney is not wearing shoes remains a mystery.

Aubrey "Po" Powell, a designer who found fame in the 1960s and 1970s as part of the design agency Hipgnosis, says the reason Abbey Road was scrutinised in this way is simple: the Beatles had stopped touring and were living professional lives that were semi-hermitic. In the days before paparazzi, this withdrawal from the public sphere created an opportunity for people to speculate about what the band were up to.

"There was no MTV, no music videos, no internet," Powell says. "Album covers were fans' only contact with the band. It was album covers and the stage and maybe a feature in Rolling Stone. That's all they got. "Bands like Led Zeppelin and Pink Floyd didn't do interviews and hardly took any photos," he says. "So the fans pored over their cover artwork looking to get a feel for what the band was about."

With his partners, Peter Christopherson and Storm Thorgerson, Powell created some of the most closely examined album covers of the rock era. They crafted sleeves for Pink Floyd (Dark Side of the Moon, Saucerful of Secrets, Wish You Were Here and The Division Bell, among others) Genesis, Led Zeppelin (Houses of the Holy), Peter Gabriel and Yes. Hipgnosis were influenced by Salvador Dalí and Rene Magritte, Powell says. Their best work had a surreal quality that added another layer of mystique to a band's image.

"None of our ideas were related to the music or the lyrics," says Powell. "Usually it was just an idea we had and then we thought: 'Who can we sell it to?' There was no message. The cover of Pink Floyd's Wish You Were Here featured two men shaking hands, one of whom was on fire. You could read anything you wanted into it." For 15 years in the 1960s and 1970s, the cover artist enjoyed a period of unbridled creativity, making covers for music that were rich enough to reward scrutiny.

Artists pushed the boundaries of what an album cover could be. Roger Dean developed a fantastical airbrushed technique used on albums by Yes, Uriah Heep and Gentle Giant. Warhol, who designed album covers for the jazz label Blue Note in the 1950s, used a real zipper on Sticky Fingers. "We lived at a privileged time," Powell says. "Money was no object and rock bands were wealthy. And they wanted to experiment. For our first album, Pink Floyd's Saucerful of Secrets, we were paid £45 (Dh276). In the end we were being paid tens of thousands of pounds.

"We hung out with Marianne Faithfull, Mick Jagger, Paul McCartney and Pink Floyd. They were our friends. I saw Cream's first gig and Jimi Hendrix's first show in London." Despite the freewheeling creative atmosphere, problems remained. Pampered rock stars could be difficult to deal with. "They were all a nightmare," laughs Powell. "Black Sabbath were a nightmare. We had a rapport with Pink Floyd; we were like the fifth member of the band but they could be difficult, too. McCartney was exacting. You'd present ideas to him and he would say: 'It's good but mine is better.' Then he'd have you do both. When you showed him the results he'd say: 'See? I told you mine was better.'"

But the most perilous band Powell ever dealt with was Led Zeppelin. "It was like a train wreck," he says. "It was dangerous because they were so rich and anything went. Also, its manager [the former wrestler Peter Grant] was extremely tough. The atmosphere was very paranoid, very funny, very outrageous." It was also a more innocent time. In their 20 years producing cover art for the biggest names in rock, Hipgnosis never signed a contract with any of its famous clients.

"Peter Gabriel, Yes, Genesis - none of them," Powell says. "It was a different time." But Jamie Reid's artwork for The Sex Pistols' 1976 album Never Mind the ******** changed the way record companies viewed album cover art, Powell says. Reid's rough-edged ransom note lettering on a lurid pink and yellow cover put paid to the ornate and suddenly unfashionable work of airbrush artists such as Dean and Hipgnosis, and started a 1980s design trend.

"These guys were doing it for £5 (Dh31)," Powell says. "The huge budgets that record companies were doling out just died." Today, things are different. Seb Marling from the design agency Village Green has designed albums for The Chemical Brothers (Surrender), Pulp (Different Class), Stereo MCs (Connected), Leftfield (Leftism), Coldplay (A Rush of Blood to the Head), Travis (The Man Who), Basement Jaxx (Remedy) and, most recently the Yeah Yeah Yeahs' new album, It's Blitz!. He says an album cover for a well-known band today costs a record company something between £5,000 and £8,000 (Dh30,686-Dh49,100).

"Record companies are now very marketing savvy," he says. "They really nail it down." Marling believes reduced fees reflect the reduced importance of the album cover to bands and their audience. "If I am an 18-year-old downloading music today I may not even see the cover art, or just glimpse it as a thumbnail on a website," he says. But both Marling and Powell agree that music and visuals are inextricably linked and that, while the album cover canvas has shrunk from 12.375 inches square of vinyl to 4.75 inches square of CD to a tiny online thumbnail portrait, there are still designers, artists and bands willing to pick up where artists such as Robert Mapplethorpe (Crazy Horses by Patti Smith) or Richard Hamilton (The Beatles' The White Album) left off. They point to the work of new, visually literate acts such as Florence and the Machine and Bat for Lashes, who are taking up the torch from the most creatively expansive 1970s rock bands.

"Natasha Khan from Bat for Lashes has a strong sense of image. A lot of ideas come from her," says Andrew Murabito, who designs cover art for her as well as for artists as diverse as The Kooks and Britney Spears. Recent standout covers have included Bob Dylan's new album, Together Through Life, Franz Ferdinand's second album, You Could Have It So Much Better, and Damien Hirst's cover for the band The Hours - a piece of art now worth £125,000 (Dh767,000). The cover of the new Pet Shop Boys album, Yes, was designed by their longtime collaborator Mark Farrow. It's a very simple multicoloured tick.

"Not many people could pull off something so simple," Murabito says, adding the image really grabbed his attention - another function of good cover art. So when the artist Peter Saville, famous for New Order's covers, said last year that the album cover is dead, was he right? "Definitely yes," Powell says. "It had a 15-year lifespan and that was the heyday. Today you can go to YouTube to hear the song. There is no mystique."

"I think Peter Saville may have had a point," Marling says. "It is definitely less important. But there are so many other avenues for a band to express its visual identity. Maybe you don't need something as 'real world' as an album cover." Eccleston says: "Vinyl sales have increased year on year for the last five years. There is a new generation of kids that are into vinyl. That's what we hear at Mojo magazine.

"The CD was created as a medium of convenience but the MP3 is more convenient and so the CD's position has eroded," he says. "Vinyl is the best audio format for sound quality so it's the best as a luxe format." For Eccleston, the return of vinyl could signal the rebirth of the large-format album cover as well. "There's a hope that artists skilled enough to create great images will come back to the big 12x12 canvas of sleeve design."