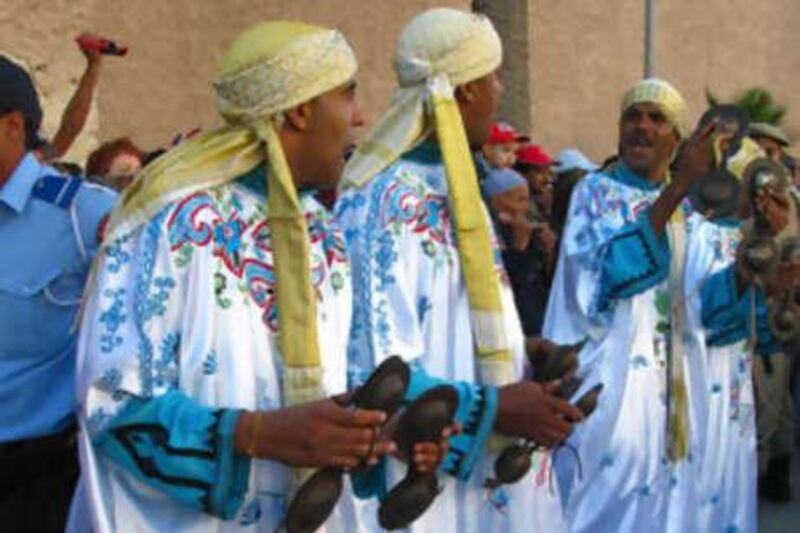

The procession begins at the Bab Marrakesh gate with groups of Gnawa in elaborate costume followed by a horseback fantasia heading up the long narrow Rue Mohamed El Qorry lined with cloth merchants and household goods, and past the gold and silver souk at the heart of Essaouira's medina on Morocco's Atlantic coast. Turn one way and you're among raw sides of lamb; the other takes you to the Bab Sba Gate and the Moulay Hassan stage, the Atlantic crashing in from the west, a full moon shining down, and the great long curve of the beach behind the stage. It is a remarkable setting for an unforgettable pageant.

It is the opening night of the 13th Gnawa Festival, which since its beginning in 1998 has become one of the unifying musical fixtures in Morocco and indeed Africa. Musicians come here from all over the world, and with them crowds of up to 400,000 packing the town's narrow blue-and-whitewashed streets, squares and riyads to see the country's leading Gnawa malaams and be delivered up to the world's heaviest trance and healing music.

As one of the musicians from the visiting reggae singer Patrice's band points out, Essaouira is the only place he knows where the dogs don't bark. This year's programme featured a strong dance element for the first time, with the opening procession culminating in the Place Moulay Hassan with a sound and movement collage of the great Gnawa Malaams and brothers Mohamed and Said Kouyou and the Georgian National Ballet, fusing the martial dance traditions of the Balkans with Gnawa's krakek percussion and ghimbri bass.

Later in the festival, one of the masters of fusion at the festival, Mustapha Bakbou, joined forces with the American dance troupe Step Afrika from Washington, combining African-inspired step and human beat-box rhythms with Bakbou's relentless drive. That the music is so popular here, and so embedded in the national psyche - evincing football-style terrace chants broiling through the huge, open-air audience - remains one of the festival's more remarkable phenomena.

"It tries to keep its identity in the roots of the area," says Titi Robin, the French guitarist and bazo uk player famed for his work with Mediterranean gypsies and Rajasthan's Gulabi Sapera. "There are so many festivals in world music that are like supermarkets with all kinds of things that you can buy, but there is no identity. I don't like this. These people take care of their roots. It is always Gnawa music and it is also open, and it is free."

His last point is salient - only the indoor, late-night concerts charge a modest admission price; the main stage performances are open to all. Robin was scheduled to appear on both platforms over successive nights, with the Qawwali singer Faiz Ali Faiz, a mighty heir to the crown of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan. Faiz is no stranger to Moroccan audiences. This is his sixth visit, though his first encounter with the Gnawa. "I find there are so many similarities between Qawwali and Gnawa," he tells me on one of the town's sun-drenched rooftops between rehearsals. "There is a difference in the melody and the sound but within minutes we found ourselves at the same point."

He has recently appeared at Abu Dhabi's Womad festival and his performance with Robin and the Issaoua de Meknes on the Moulay Hassan stage saw the great Qawwali singer opening up and virtually turning himself inside out with the passion of his performance, supported by the flowing decoration of Robin on bazouk and rebab and the pulse of the Issaoua drums. The crowd responded with an almost palpable warmth.

At the following night's set at the Dar Saoui, I watched as Robin stared down transfixed from the gallery on to the platform below as the Issaoua ensemble performed for more than an hour without a break, before slipping down and joining them with Faiz Ali Faiz in a session that stretched towards the dawn. It was one of those classic moments you'll find at Essaouira - as long as you stay up late enough.

All over town, Gnawa is the sound that you hear - from street stalls, from stages, from groups in the street, or on the windy ramparts that circle overlooking the Atlantic. Those ramparts were built by the Portuguese in the 16th century - the same period as the music's origins. The area has been settled since prehistoric times, and was Morocco's main port until this century and remains an abundant fishing port - below the Moulay Hassan stage you'll find open-air fish stalls grilling catch fresh from the ocean, and at the end of the port is Chez Sam, the restaurant where Orson Welles feasted while filming his Othello here in 1951.

As a festival location it's hard to beat, and even the light seems to vibrate to the insistent sounds that waft across the medina rooftops into the early hours. One of the sounds you always hear at the festival is the crowd's roar of approval for local hero Mahmoud Guinea, who performed this year under a full moon to an audience stretching the length of the ramparts, their collective energy cresting and falling to the dictates of Guinea's powerful voice and subterranean ghimbri.

He has a profound presence, playing as if he's planted his feet in the centre of the earth. At its most powerful, the ghimbri hits you somewhere in the solar plexus and plays out to the periphery of your vision. And Guinea is powerful indeed, renowned for his command of the healing Lila ceremonies that remain the fundament of Gnawa culture, even after 13 years of festival and huge audiences. "You don't become a Malaam randomly," he says. "You have to grow in a milieu where you have the cultural history. I grew up in a family already born into teknowit [authentic Gnawa]. My father tested me to see if I could control the process of the Lila and the trance. I had to perform a Lila for female Gnawa, and to put them into trance. And that is how I became a Malaam. I played them into trance. Like a conductor."

For his performance on the Bab Marrakesh stage, he delivered two hours of teknowit Gnawa, and the force and weight of the sound was magisterial, overpowering, working itself deep into the brain stem, to the sources of enchantment and musical intoxication. "Our music speaks to everyone, without barriers. It has a very spiritual dimension and it attracts people so that they almost become addicted to it. It's a therapy that is universal." He gives me an example. "We travelled to Italy and met some psychiatrists who invited us to a clinic where we performed and the doctors noted the patients responded so easily to the music, because it heals the spirit. And now every year we receive those patients and do a special Lila for them."

There is no one more "teknowit" than Guinea, but he is also an enthusiastic support of fusion - the likes of Carlos Santana have shared stages with him - and this year saw his guest Daby Toure etching his lean guitar lines against the weight of Guinea's playing and the troupe's sound wash of krakeks. "We have the same rhythmic base and same origins," says Guinea. "I come from Timbuktou, he from Senegal. We are both African, and it felt as if we had been performing together for years, it is so beautiful.

"I find when I perform with African artists the fusion is so easy because it is so similar. Sometimes we don't even need rehearsal. We just get in and start playing." The natural fit between Guinea and Daby Toure echoes Gnawa's dense musical thread running from Morocco through the Sahara into Mali, Gambia, Senegal and beyond. And it is the sound of Guinea's ghimbri and voice lulling the mind, or the intimate, late-night acoustic concerts with Titi and Faiz Ali Faiz in Dar Souiri that linger longest after the stage lights have been dimmed in the great squares, and the narrow streets of the medina are quiet again - and the dogs still do not bark.