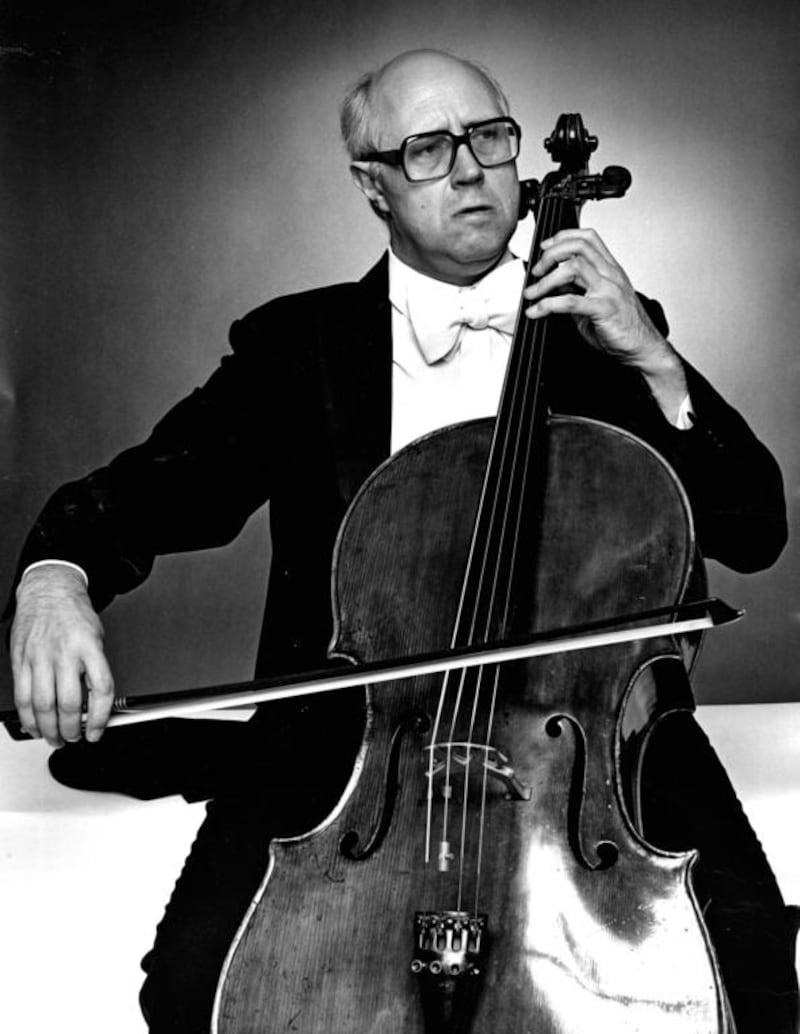

If there is anyone who deserves a film to be made about their life, it is Russian cellist Mstislav Rostropovich.

This colossus of the concert hall – who died in April 2007 at the age of 80 – was as big in life as the notoriously warm sounds he produced from the cello. And his story is intertwined with the history of the 20th century – from the traumas of the Second World War, through the Cold War’s ideological struggles to the subsequent thaw of glasnost.

He experienced the dizzy heights of fame as an international superstar and the crushing destruction of a Soviet dissenter.

But despite the seriousness of his craft, his stocky physique and commanding presence, Rostropovich was a playful character much loved by all he encountered.

To mark the 10th anniversary of his death, there are a number of special releases to enjoy. Last month, Warner Classics released Mstislav Rostropovich: Cellist of the Century, an epic 43-disc set featuring a 200-page book and many rare recordings.

This month, collectors (and vinyl fans) can look forward to a limited-edition LP of Dmitri Shostakovich's Cello Concerto No 2, as played by Rostropovich in 1966 as part of the Concerto's premiere at the Moscow Conservatoire's Great Hall, with conductor Yevgeny Svetlanov and the USSR State Symphony Orchestra.

Yes, the vinyl comeback has now reached the classical-music market, although this release also has special historical significance – it is the first time the recording has been issued on LP. The grand occasion is part of the celebrations for this year’s International Record Store Day.

But, this being Rostropovich, the story does not end there. He and Shostakovich had a profoundly special relationship – one that was tainted by the undulating political climate of Soviet Russia.

"He was the most important man in my life, after my father," Rostropovich told The New York Times in 2006.

The pair met at the Moscow Conservatory, where Rostropovich was a student and Shostakovich a teacher – and quickly developed a strong mutual admiration.

It was also at the Moscow Conservatory that the cellist first encountered the uncompromising might of the Soviet machine under Stalin.

In 1948, Shostakovich, along with other composers, including Prokofiev and Myaskovsky, fell foul of the authorities and came under public attack – just one of the many purges the artistic community faced during the Stalin era.

Although young, Rostropovich came face-to-face with the fallout when he arrived for Shostakovich’s class at the conservatory.

"My colleagues were staying on the first floor, not the fourth floor," he told Gramophone in 2007. "There was a sign, saying Shostakovich would not be a professor any more."

Rostropovich remembers Shostakovich sitting alone in the great hall, while fellow professors stepped forward to denounce him.

“He had to suffer a lot in his life,” the cellist recalled.

Rostropovich, however, stuck by his friend. And Shostakovich managed to bounce back, especially after Stalin’s death in 1950.

But the cellist himself got a nasty taste of what his mentor had gone through when he came out in support of dissident writer and Nobel Prize winner Alexander Solzhenitsyn in 1970.

It began when – out of frustration – Rostropovich sent a letter of protest to state-run newspaper Pravda in 1970.

“Explain to me, please, why in our literature and art, so often people absolutely incompetent in this field have the final word,” he wrote.

“Every man must have the right fearlessly to think independently and express his opinion about what he knows, what he has personally thought about and experienced, and not merely to express with slightly different variations the opinion which has been inculcated in him.”

Pravda did not publish the letter but the foreign press did – and Rostropovich found himself on the wrong side of the law. The relative protection he had enjoyed as a member of the artistic elite evaporated. Permission to travel abroad was revoked and concert bookings at home dried up.

When he was finally allowed to play in Europe again, in 1974, he and his wife, Galina Vishnevskaya, never returned home, instead becoming high-profile exiles in Paris.

“I will not utter one single lie to return,” he said in 1977.

Back in the USSR, discussion of Rostropovich became taboo. In 1978, his Soviet citizenship was revoked, giving him the inglorious status of an “unperson”.

Amazingly, it is thanks to a resourceful Soviet archivist that the historic 1966 recording of Shostakovich's Second Cello Concerto still exits. Whoever it was – unsurprisingly, the person chose to remain anonymous – hid the original tape in a mislabelled box, which was only rediscovered in the 1990s following the collapse of the Soviet Union.

It is a fascinating recording and one that shows the man at the height of his powers. After witnessing Rostropovich’s playing in 1960, British composer Benjamin Britten commented in awe: “This was a new way of playing the cello.”

A numbered, limited-edition pressing of 3,000 copies of Shostakovich: Cello Concerto No 2, featuring Mstislav Rostropovich, the USSR State Symphony Orchestra and Evgeny Svetlanov, will be available on International Record Release Day on April 22.

• Rostropovich: Cellist of the Century anniversary boxset costs US$120.89 (Dh443.94) from www.rostropovich2017.com

artslife@thenational.ae