At the end of his 2013 novel An Officer and a Spy, British author Robert Harris thanks his wife for, over the course of his fiction-writing career, sharing a house with "successive waves of Nazis, codebreakers, KGB men, hedge fund managers, ghostwriters and assorted ancient Romans; this time it was officers of the French General staff."

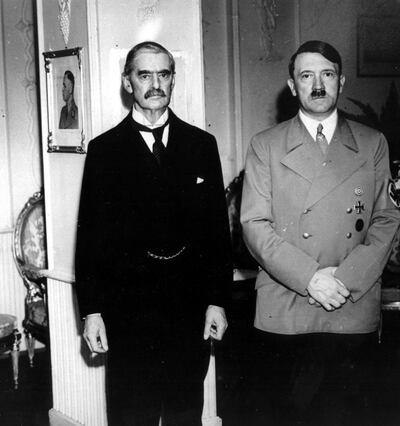

For Harris's last novel, Conclave (2016), which deals with the rigorous trial of electing the right Pope (as one character intones: "God doesn't do recounts"), the Harris household was presumably filled with scheming cardinals. For his latest novel, Munich, an electrifying dramatisation of the 1938 conference and 11th-hour negotiations to secure peace in Europe, Harris gave houseroom to one unlikely and one unwelcome guest – Neville Chamberlain and Adolf Hitler.

The latter casts a dark shadow over two of Harris's books: his bestselling debut novel Fatherland and the equally gripping non-fiction work about the dictator's diaries, Selling Hitler. However, Munich sees Harris rising to the challenge of, for the first time, turning the Führer into a character.

"That was the most frightening thing about writing the book," Harris tells me over lunch. "Hitler scorches the page. You have to handle him with great care. When I first tried to introduce him, it felt so weird and very cheap, like a third-rate piece of writing. I rang my editor and said, 'I may have to abandon this.' She got on a train, came down and talked me off the ledge."

With Chamberlain – the British prime minister whose policy of appeasement merely postponed rather than prevented war – Harris found himself with more creative licence. "I'm fortunate in that I don't think he appears in any work of fiction. So I had the field to myself."

His Chamberlain is a stiff relic from the Victorian era but by no means the spineless statesman he is often portrayed as. "I'm not trying to whitewash him," Harris stresses, "but I think he is the opposite of the feeble man with the umbrella. He was actually a tough, wiry, ruthless, clear-eyed politician. He overestimated his rapport with Hitler but was under no illusions about the kind of character he was."

Harris is a delightful interviewee. Sharp, chatty and witty, he entertains with a wealth of anecdotes, opinions and insights. Sometimes he talks as acclaimed author of historical fiction, other times as switched-on observer of current events.

The high-stakes tension leading up to the Munich Agreement and the clashing objectives of its significant players provide perfect material for Harris. Back in 1988, he made a TV documentary called God Bless You, Mr Chamberlain to mark the 50th anniversary of the conference. Since then he has maintained a mild "obsession" with the subject. But why?

"I think because quite early on, I realised there was more to the Munich story than there is in the popular imagination. It has become a synonym for weakness and surrender. Throughout all those conflicts – the Iraq War, the Libyan attack, the Syrian War – there was the constant jibe of 'appeaser' or 'Munich' at anyone who hesitated as to whether military action would be the right course. Munich is a very live issue."

______________

Read more:

[ Netflix documentary series explores how Hollywood changed World War II and vice versa ]

[ From the tsar to Lenin, revisiting the Russian Revolution in new reads ]

______________

One of Harris's heroes in the novel, a German diplomat and member of the anti-Hitler resistance, urges Britain and France not to sign any agreement. Hitler is intent on war, he explains. He has plans to invade Czechoslovakia and expand the Reich. What is being done at Munich "will one day come to be seen as infamous". But, I ask Harris, could anything else have been done?

"I think the absolutely key thing is that Hitler wasn't bluffing in 1938. He wanted the war and so regarded Munich as a setback. In the end it proved impossible to appease him."

I risk incurring Harris's wrath by telling him that initially I didn't think the book was going to work as a thriller, because what we hurtle towards is a known conclusion. Did he feel hamstrung? Was it harder to serve up thrills?

"I think you get the thrills from other areas such as the individual characters – what happens to them, what is their story, what is their mystery? You get the frisson of what it was like to be in the room with Hitler and Chamberlain. You can still have a good thriller if you know the outcome. For instance, The Day of the Jackal: just because Charles de Gaulle wasn't assassinated, it doesn't stop it being a thrilling cat-and-mouse game."

Harris's novels are regularly praised as being intelligent thrillers. Like its predecessors, Munich is a thoroughly researched, meticulously plotted and hugely engaging drama. And yet despite its merits it is unlikely to be nominated for any top literary awards. I ask Harris how he feels about the never-ending debate between the worthiness of literary fiction versus the supposedly cheap thrills offered by less well-regarded genre fiction.

"Some of the greatest books in history are thrillers," is his quick comeback. "Nineteen Eighty-Four is a thriller on almost every criterion. A lot of contemporary literary fiction seems to just be inspecting itself endlessly. I concede that I'm not an experimental writer in any way but that's not my interest. My interest isn't the business of writing, it is the business of the world, the age-old dilemmas of morality and politics, appeasement and war, faith and power."

So no stylistic or linguistic tricksiness? "It's not language that is important," he says, "it's the use to which you put the language. I agree with Orwell that good writing is like a pane of glass. You're not even aware it's there. You just see through to what the writer wants to convey."

Along with Orwell, Harris's influences take in Joseph Conrad, Evelyn Waugh, Graham Greene and John le Carré. He remembers losing himself in books by these writers and others in his childhood. "It wasn't a background with much money," he says, "but it was privileged in other ways."

His early memories include watching his father at work in his printing plant on a Saturday morning. "I would be taken in and seated with a pile of paper and left for three hours with the smell of the ink and the noise of the press. It definitely had an effect on me."

With no shortage of paper and ink, Harris made newspapers and maps of imaginary countries and cities. At the age of 13 he wrote a play about someone who had set up their own religion. This is interesting, as the adult Harris is a markedly different beast. All his novels are based on facts. He has no truck with fantasy and is on record as saying that, for him, "magic realism is garlic to a vampire".

He laughs. "Yes, but there was a concrete realism to all this. There were no airy spirits. They were alternative lands and newspapers but it was all based around institutions. It was an odd interest in the real world but filtered though imagination. And I really do like knowing my world. If I can't get the place, I can't get the book."

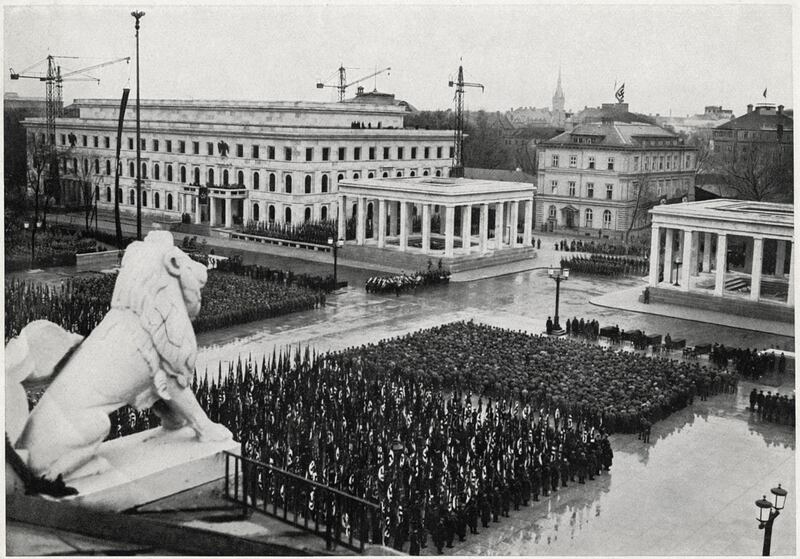

He took great pleasure in reprinting a map of the Führerbau, the building where the conference took place, at the beginning of the book. He was given access to Hitler's apartment which is closed to the public, and was amazed at how intact it was. "I've never been in a place quite so full of ghosts," he says.

Harris set up a school newspaper when he was 14 and a village newspaper when he was 16, and then went on to edit the student paper at Cambridge University. After graduating he embarked on a career in journalism. Then in 1992, Fatherland appeared with its intriguing counterfactual premise: what if Hitler had won the war? The boy who created imaginary nations and newspapers had grown up and written a novel that reimagined history.

Harris reveals that the idea for Munich predates Fatherland. "I've been wanting to write about Munich for 30 years," he explains. "But I couldn't see it. And then last year I did."

How does he feel about this year? In the German election, the far-right AfD (Alternative for Germany) has just become the country's third-largest party. Is history repeating itself?

"The great gesture of Angela Merkel of bringing in a million refugees, as so often with the law of unintended consequences, personally I think that was responsible for Brexit – that sense that she could unilaterally have a million immigrants into Germany who then became European citizens, who then automatically have a right to come to Britain. That focused people's minds that Britain had lost control of its borders and that is something that liberals have failed to address. So, to some degree, Brexit and the rise of AfD, they are a reaction.

"The most frightening thing about AfD is it is a more respectable party than the Nazis and I don't think its influence is going to diminish soon."

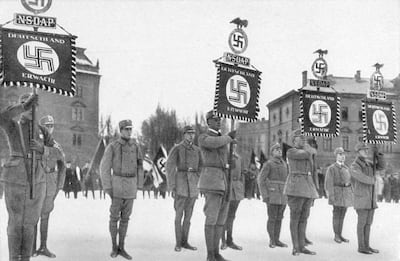

Harris admits to being more concerned about the United States, "where swastikas are being paraded openly", and with a president who is "not exactly full-throated in his denunciation". I quote him a line in Munich from a particularly repellent Nazi: "We have made Germany great again." The (Donald) Trump-like echo is unmistakable. "I don't want to make glib comparisons," he says, "but obviously Trump is playing a racial divide game in ways that enable him to wriggle and say he is not, but we all know what he is doing."

Harris knows more than most. "I've known politicians, observed politics at close quarters. Power audits people like nothing else, it reveals their strengths and weaknesses. You hold power too long and it will destroy you. It's like a radioactive material, it has to be treated with great caution and be kept behind protective walls. And the frightening thing is who gets their hands on it, just like who gets their hands on uranium."

A stimulating hour comes to end with some sobering last words. I ask if any parallels exist between the world then and now.

"First of all I've learned not to strain after parallels," he says, with a grin. "But there are obvious parallels. We meet on the day that the Social Democrats in Germany scored their lowest share of the vote since 1933. That's a slightly ominous statistic. There is a 1930s vibe in the air.

"The thing about Munich is it dramatised how a peace-loving democracy coped with regimes that had a completely different agenda. We very much face that now and are likely to do so more in the future."