Slowed down by illness and age, Muhammad Ali, arguably the greatest boxer the world has ever seen, is now a shambling shadow of his former self. But thanks to archive footage in the British filmmaker Stephen Frears's HBO docu-drama, Muhammad Ali's Greatest Fight, the young, virile and voluble champion of old was resurrected in Cannes this week. And just by being himself, he set the screen alight.

The film catches Ali when, at the height of his powers, an act of conscience forced him out of the ring.

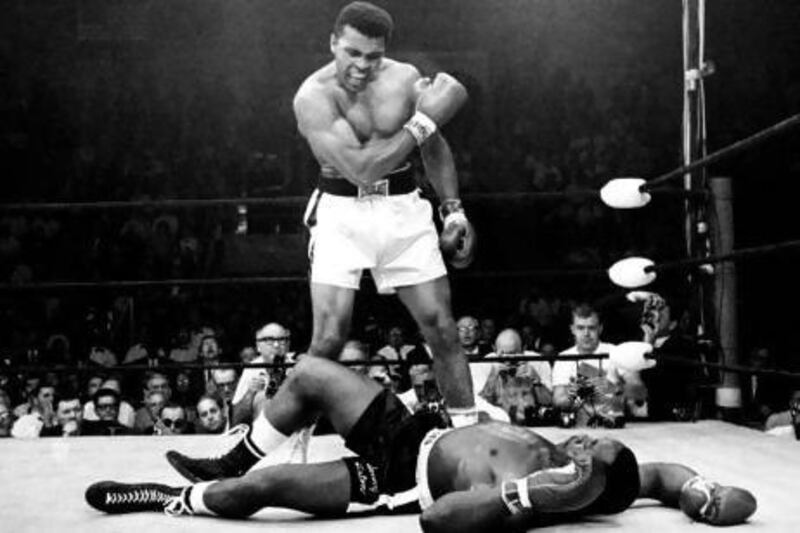

Following his defeat of the reigning heavyweight champion of the world, Sonny Liston, in 1964 (“I showed the world,” shouted the cocksure 22-year-old in triumph), the boxer revealed that he had joined the Nation of Islam. Henceforth, he would no longer be known by his “slave name”, Cassius Clay, but as Muhammad Ali. Now a Muslim pledged to peace, Ali refused to be drafted into the US military because he was opposed to the Vietnam War.

“War is against the teachings of the Holy Quran,” he declared. “I’m not trying to dodge the draft. We are not supposed to take part in no wars unless declared by Allah or The Messenger. We don’t take part in Christian wars or wars of any unbelievers.”

The reasons for his conversion are not explored in the film, and the gruff, frustratingly laconic Frears, sitting alongside his screenwriter, Shawn Slovo, has no answers. Slovo, though, says there is a hint in one of the archive clips.

“He partly says it when he says: ‘If it wasn’t for the Nation of Islam I would be just another bum, or be called a ‘bum Negro’, drinking and smoking.’ He was an athlete,” she says, “so I don’t think that was a tendency. But I think it kept him on track and gave him a set of values and beliefs that made sense to him.’

Adds Frears: “He turned out to be a very moral character in somewhere where you didn’t expect. Heavyweight champions aren’t usually morally scrupulous.”

Ali paid a heavy price, though. Convicted of draft evasion (his application for conscientious objector status was denied), he was given a five-year prison sentence (he remained free on appeal) and fined US$10,000. His passport was withdrawn, he was stripped of his heavyweight title and banned from boxing in the US. Ali would not be KO’d and stuck to his religious convictions, and this proved irresistible to Slovo.

“He lost millions of dollars and he compromised his health by stopping fighting for three and a half years at the prime of his life,” she says. “That’s a story as far as I’m concerned, isn’t it?”

Luckily for the filmmakers, there was a wealth of footage from the period featuring the inimitable pugilist, obviating the need to cast an actor. In truth, the thought never crossed their minds.

"Then the film would be judged on whether the actor was good enough, like Michael Mann's Ali was," Slovo says. "And why tell his story, why dramatise it, when he can tell it himself so much better?"

Ali’s fate eventually landed with the predominantly white justices of the US Supreme Court in 1970-71, which is the real focus of Frears’s film. Instead of sticking with Ali, the director and Slovo document the political and legal arguments that eventually resulted in a somewhat fudged decision to overturn Ali’s conviction.

“That is very common in the court,” says Slovo. “Very common in arguments. It’s all on technicalities and legal precedents, so that is how they can make changes.”

The writer had to fill out much of what actually went on because “there is nothing on record”, she says. “So you can only extrapolate from the judgements, and from what you know about the different characters of the justices. All those justices [in the film] are based on the real justices, but there’s so little written about the Supreme Court that it gave us a lot of freedom, a lot of leeway, because it’s such a secretive organisation.”

Although she could draw on justices’ memoirs, the Ali case usually only took up a few lines. This doesn’t mean they didn’t consider it important, however.

“Justices are appointed for life,” Slovo explains, “so some of them have got 60 years on the bench. So I think it’s not that Ali’s marginalised, it’s just that it takes its place within 60 years of momentous legal decisions they made.”

The film raises questions about the independence from political influence of the presidentially appointed justices, and of the court itself, that have great contemporary relevance. Today, as then, the Supreme Court is polarised, and there are fears that Roe V Wade, the momentous decision legalising abortion across most of the US, will be reversed soon. “If that happens, there will be trouble,” says Frears.

“What our story is about,” suggests Slovo, “is will those nine justices be able to respond to a new zeitgeist in America? And that’s, I think, what the criticism of the contemporary Supreme Court is, who are not with the country in terms of the legislation and the way they’re voting on the issues.”

Ali emerged victorious in the court and again in the ring, and despite the film's perspective it's his indomitable spirit and charisma – captured forever on video and celluloid while the man himself sadly declines – that give Muhammad Ali's Greatest Fight its greatest moments.

Follow us

[ @LifeNationalUAE ]

And follow us on Facebook for discussions, entertainment, reviews, wellness and news.