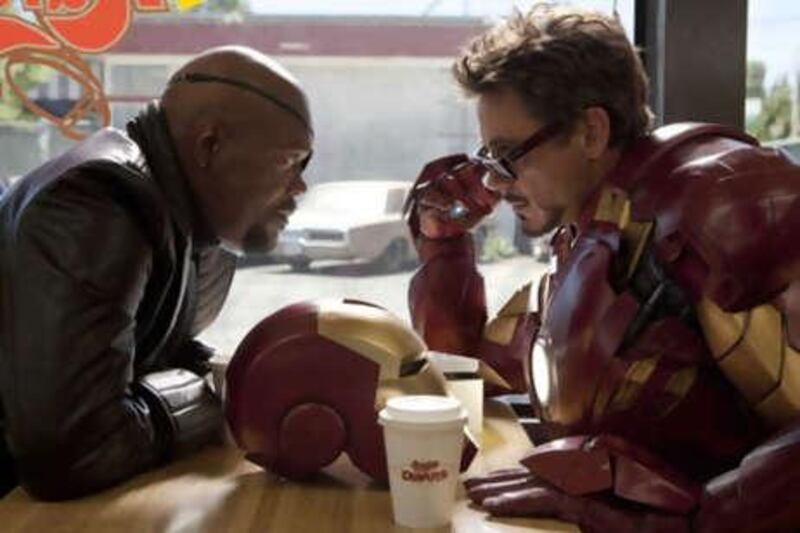

Dashing, intelligent and debonair. Tony Stark, and his alter ego Iron Man, is on a mission to maintain world peace. The playboy American industrialist, brought to the big screen by Robert Downey Jr, seems to fit every superhero stereotype. But look a little closer and the body count, not to mention gratuitous explosions and double entendres, rack up in this "superhero" movie on a scale never seen in the adventures of Superman or Spider-Man. And as for Iron Man's drinking problem. ...

So it's no surprise that a new academic study has revealed Iron Man's antics don't actually constitute heroic behaviour at all. In fact, they're actually rather dangerous for impressionable young boys, the annual convention of the American Psychological Association was told last week. The movie superhero of the 21st century, it seems, is no longer the role model that he once was. "Today's superhero is too much like an action hero who participates in non-stop violence; he's aggressive, sarcastic and rarely speaks to the virtue of doing good for humanity," argued psychologist Sharon Lamb, from the University Of Massachusetts, at the conference. "When not in superhero costume, these men, like Iron Man, exploit women, flaunt bling and convey their manhood with high-powered guns."

Lamb has the figures to back it up, too. She surveyed 674 boys aged four to 18 in her quest to understand what they were watching on television and at the movies. The study revealed just two types of male behaviour, superhero-styled aggression, and its polar opposite, couldn't-care-less antipathy. So surely, if the superhero is promoting a macho, violent stereotype, then the slacker who wanders around in a daze is slightly preferable? Not according to Lamb.

"Slackers are funny," she said, "but not what boys should strive to be; slackers don't like school and they shirk responsibility." These results might sound like the sentiments of a killjoy academic who would rather we all watched an art house movie with a moral. But perhaps Lamb does have a point. Superhero films have unquestionably become either darker or more violent in recent years. The first Iron Man was actually a rather interesting take on what a superhero might mean post September 11, until the director Jon Favreau seemed to lose his nerve and made the last 30 minutes an explosion fest. Christopher Nolan's new take on the Batman films is brilliant, but shot through with haunting tragedy. Despite the presence of a joker, there's not much joy in them.

And one of the most controversial movies of 2010 is without doubt Kick-Ass, where an ordinary teenager decides to become a "super-hero", but in a graphically violent and profane way. Its makers would argue that it's not for children in any case, and the certification certainly backs that up. But it's become almost a badge of honour for youngsters to find a way to see it, just as with the gratuitous Robocop in the 1980s.

So no-wonder Lamb is harking back to the good old days. Of course, it's not as if the comic book heroes of yore indulged in pacifism, using only their wit and imagination to overcome evil. In the Christopher Reeve film Superman III, the superhero becomes casually destructive. He blows out the Olympic Torch and straightens the leaning tower of Pisa. But this is part of a shocking plot twist rather than his default position. More typically, Reeve's Superman diverts nuclear missiles into outer space or weakens earthquakes. Villains are tied up - not blown up - and handed over to the police. Superman saves people with the minimum amount of violence.

"The comic book heroes of the past did fight criminals," adds Lamb, "but these were heroes boys could look up to and learn from because outside of their costumes, they were real people with real problems and many vulnerabilities." It's not just eminent psychologists who worry for the future of the superhero. When the likes of Alan Moore, creator of 1980s parallel-world comic Watchmen, says he will abandon the genre, something really must be wrong. Moore, after all, is perhaps the most highly regarded comic writer in history.

"I've come to the conclusion that what superheroes might be, in their current incarnation at least, is a symbol of American reluctance to involve themselves in any kind of conflict without massive tactical superiority," he told the London music newspaper Stool Pigeon last month. "That's not what superheroes meant to me when I was a kid. To me, they represented a wellspring of the imagination. Superman had a dog in a cape [the white, doberman-like Krypto]! Hehad a city in a bottle! It was wonderful stuff for a seven-year-old boy to think about. But I suspect that a lot of superheroes now are basically about the unfair fight."

And while the Watchmen superheroes aren't exactly straightforward good guys, Moore's comic book series was at least spellbindingly imaginative and intelligent. Its film adaptation of last year is so stacked full of ideas, it's actually rather difficult to follow. Admittedly, over-analysing what a superhero means in 2010 is slightly ridiculous. After all, film adaptations of well-loved (and often quite dark and violent) comic books are by their very nature explosive and sexy. Most important of all, they're escapist fun, and no one is suggesting a return to the camp capers of the Batman and Robin television series. When Nolan concentrated on the "dark" element of the Dark Knight, he was only being true to the original comics.

Still, it will be interesting to see what he does with the Superman reboot he's working on. After all, the Clark Kent that Christopher Reeve made his own, the ordinary newspaper journalist with a penchant for saving people and dreams of getting the girl, seems to come from a different, more idealistic and perhaps more innocent world altogether. Give him the hard-edged, nihilistic treatment and it's a slightly depressing verdict on the darker times we live in. No wonder Sharon Lamb thinks we need heroes.