More than 70 years after his death, the life and work of a Lebanese poet, writer and painter are set to inspire another generation of fans.

This week marks the UAE opening of Kahlil Gibran’s The Prophet, an animated version of one of the classics of 20th century literature, produced by Salma Hayek, who adds her voice to the film along with a host of Hollywood stars, including Liam Neeson, Frank Langella and John Rhys-Davies.

What is it about Gibran’s message that continues to resonate in 2015?

“There is something timeless about his work, especially The Prophet, where anyone and everyone at whatever time in their life can pick it up to read and will connect with his words on some level,” says Dr Tarek Chidiac, president of the Gibran National Committee.

“Gibran wrote about the soul and focused on humanity and what connects us, rather than divides us.”

The man sometimes known as the Arab Shakespeare left a collection of more than 15 works, including two published posthumously – The Wanderer in 1932 and The Garden of the Prophet in 1933 – and hundreds of paintings and sketches.

But it is Gibran’s masterpiece, The Prophet, that remains his greatest legacy.

Since its publication in 1923, The Prophet has never gone out of print or fashion.

Translated into 50 languages, and with worldwide sales in the tens of millions, it has made Gibran the third best-selling poet of all time, behind Shakespeare and Lao Tzu.

Romantic, spiritual, sorrowful and inspirational, The Prophet features 26 themes such as love, marriage, children, joy and sorrow, crime and punishment, reason and passion, pain, time, good and evil, religion and death.

It is hailed by many as a kind of a self-help book that comprises a series of philosophical essays written in English prose.

This newest incarnation has taken more than five years to complete and is written and directed by Roger Allers, director of Disney’s The Lion King.

Co-financed by the Doha Film Institute, Participant Media, and other regional and international organisations, it premiered in Lebanon last week.

The film tells the story of Al Mustafa, believed to be based on Gibran himself, a prophet who awaits passage home on a ship after being away for 12 years.

Emirati animator Mohammed Harib was one of the contributing animators, with his segment combining watercolour elements for the book’s On Good and Evil chapter with a nature-centric montage.

Harib has admitted that he had not read The Prophet before the film project, but after reading it he became one of its millions of fans.

“It’s a really amazing book. It’s not written by human hands, there’s something godly about it.”

To celebrate the coming film, the Dubai International Writers’ Centre at the Shindagha Heritage Village celebrated Gibran’s legacy with a cultural event last month, with guest speakers including Dr Chidiac, and Lebanese TV personality Georges Kordahi, who read lines from Gibran’s work.

Also taking part was Nadim Sawalha whose play based on Gibran’s life, Rest Upon the Wind, was performed in Abu Dhabi and Dubai last month.

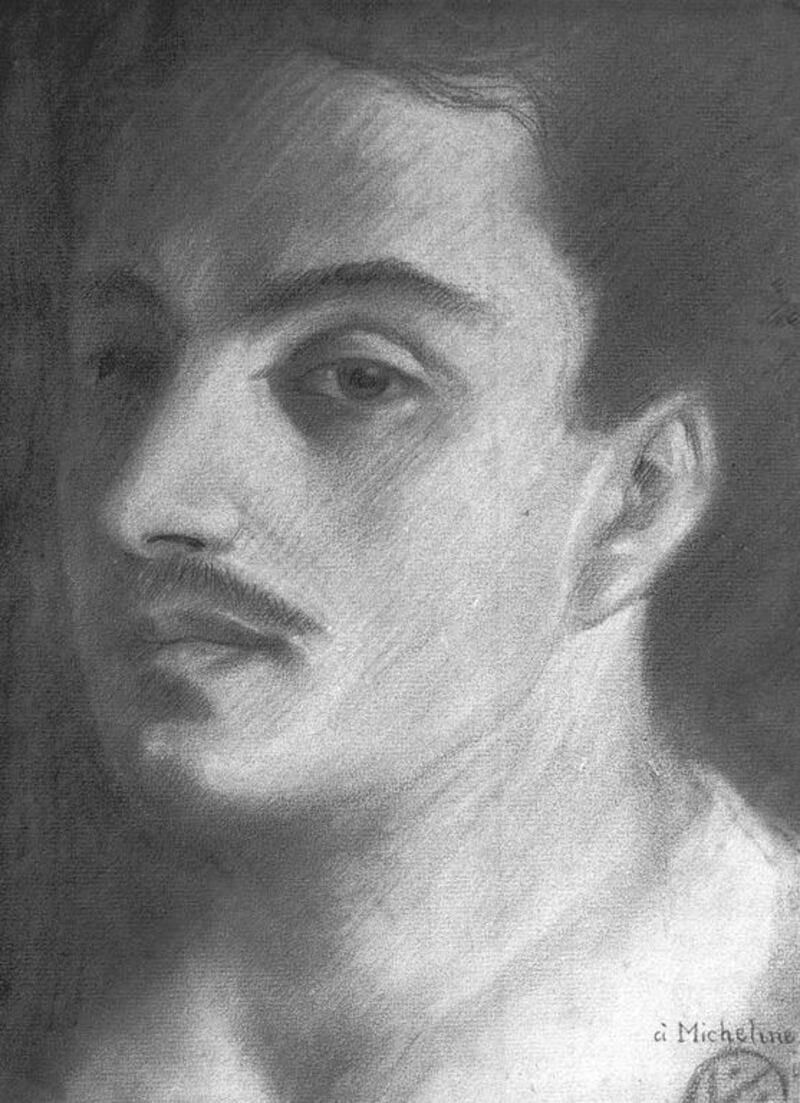

Dubai honoured Gibran as far back as 1972 with a postage stamp featuring his portrait.

The UAE will get an extra taste of Gibran this year when 30 of his drawings will be shown at the Sharjah Art Museum in October, at an exhibition organised by the Gibran National Committee and the Sharjah Museum Department.

"People who haven't visited the Gibran museum will get to see a different side to Gibran, from how he saw himself in his self portraits, how he viewed his family, and how he commented on the world around him through his art," says Dr Chidiac.

“Gibran’s work keeps coming back again and again, sometimes as quotes used by world leaders, sometimes as plays, sometimes as lyrics in songs, and this time as an animation.”

The Gibran National Committee is a non-profit organisation formed in 1934 to preserve and protect his legacy.

The committee holds the exclusive rights to manage literary and artistic works, and manages the Gibran Museum in his native town of Bsharri, where his 440 original paintings and drawings, library, personal effects and handwritten manuscripts and even furniture are displayed.

Originally a grotto for monks seeking shelter in the 7th century, the Mar Sarkis (Saint Sergious) hermitage became Gibran’s tomb and then his museum in 1975.

“What is ironic is that while he is very famous and well read in the western world, he is not as popular in the Middle East,” says Dr Chidiac.

“Partly perhaps because of its name, The Prophet, some of the more religious and conservative people have avoided reading it, or misunderstood it.”

“There may be still a lack of cultural sensitivity, openness and awareness in the Arab world to read Gibran’s work with an open mind and an open heart, and look for connections instead of criticisms.”

One of Gibran’s turning points came when he was just 6 years old.

He was given a collection of fine art Leonardo da Vinci prints by his mother and was so impressed by the Italian master that he later described him as “like a compass needle for a ship lost in the mists of the sea”.

Gibran owed much of the success of his English language writings to his patron and lover, Mary Haskell, a progressive Boston school headmistress who became his editor.

Haskell supported him financially throughout his career until the publication of The Prophet in 1923.

Gibran’s will reflected this close bond, stating: “Everything found in my studio after my death – pictures, books, objects of art, et cetera, goes to Mrs Mary Haskell Minis, now living at 24 Gaston Street West, Savannah, Ga. But I would like to have Mrs Minis send all, or any part of these things, to my hometown, should she see fit to do so.”

One of the interesting points raised at the Dubai event is the animators’ choice to spell Gibran’s name as Kahlil rather than Khalil.

“That is how he used to sign his work. For in America, that is how they would have pronounced his name and misspelled it as such when he arrived there as a child,” says Haytham Naser, the film’s executive producer.

Gibran migrated to the United States with his family in 1894 but always signed his full name in his Arabic works as Gibran Khalil Gibran.

In his English writings, he dropped the first name and changed the spelling of “Khalil” into “Kahlil” at the instigation of his English teacher at the Boston school he attended between 1895 and 1897.

“We wanted to keep the production as true to his story as possible. He signed The Prophet as Kahlil Gibran, and so we kept it as such,” says Mr Naser.

Gibran died of liver cancer on April 10, 1931, at the age of 48, in a New York hospital. Nationalistic till the end, he died 12 years before Lebanon gained its independence.

On his grave is written: “I am alive like you, and I am standing beside you. Close your eyes and look around, you will see me in front of you.”

rghazal@thenational.ae