'See humanity in a new light'. So say the posters for Louvre Abu Dhabi that now line the road to Saadiyat Island’s new museum peninsula.

It’s a smart tagline for an institution that has dedicated itself to rewriting the history of humanity. And for a building that relies for its signature effect on the sun and Jean Nouvel’s much-vaunted Rain of Light, which shine through the building’s complex canopy, dappling its precincts and walls.

But it's only a visit to the museum that also reveals how literal the phrase is. At their best, Louvre Abu Dhabi’s galleries are bathed in sunlight, reflected or muted in some places, bright and direct in others, but when this literal and metaphorical reflection and illumination combine, the effect is exhilarating.

After navigating the museum’s austere security entrance and ticketing hall and bypassing its boutique - the shop boasts the largest collection of art books in the capital - Louvre Abu Dhabi’s alternative approach to art history begins in its main hall with a 13-metre-wide abstract painting by Cy Twombly that sits beneath a raking skylight.

Rendered in a blue that's reminiscent of the ceiling the artist painted for the Louvre Museum in Paris in 2010, the nine canvases of Untitled I-IX (2008) are covered in loops of thin, white 'pseudowriting' - neither calligraphy nor graffiti – that contrast with the rigid geometry of Louvre Abu Dhabi's dome.

Peek inside the galleries of the Louvre Abu Dhabi

Although it is likely to be overlooked by visitors who will be keen to enter the museum proper, this subtle dialogue between Twombly’s art and Nouvel’s architecture is the first of many visual conversations that define Louvre Abu Dhabi’s displays and its new approach to the history of civilisation.

Dedicated to focusing on moments of cultural exchange and encounter rather than crisis and conflict, the museum sets out to explore our common humanity rather than the things that divide us through the display of similar or thematically linked objects from disparate cultures and civilisations.

It’s a measure of what you encounter in the museum’s first gallery, the Grand Vestibule, that it makes 20 square metres of Cy Twombly feel like something of an understatement.

Simultaneously a microcosm of the museum as a whole and a room like no other, the vestibule is designed as a place for visitors to orient themselves geographically and intellectually and as a kind of visual preface for the narrative that is to come.

Featuring a map of the UAE’s coastline set into its floor, the room is decorated like a traditional maritime chart, with a compass rose at its centre and lines of navigation that radiate up its walls and across the ceiling towards another skylight that also reveals the dome above.

In this instance, the museum’s mighty canopy becomes more like a celestial vault whose geometry descends from the heavens and whose rain of light solidifies into nine prismatic display cases, each of which contain objects that illustrate the different approaches various cultures take to the same universal themes.

One case, which includes a medieval French sculpture of the Virgin Mary and infant Jesus, a 19th century maternity figure from Congo’s Yombe culture and an ancient Egyptian statue of the goddess Isis nursing the god Horus, her son, investigates the common gesture of love from a mother to her child.

Another deals with humanity’s mastery over nature – using equestrian figures - while a third features golden funerary masks from the Levant, China and Peru to examine the longstanding and universal links between gold, death and the afterlife.

“Why is it that so many cultures covered the faces of their dead in gold?” a discreet curatorial note asks. “Does gold, as an incorruptible substance, confer eternal life, liberating our existence from the finite realm?”

Despite raising more questions than answers, the inference of the Grand Vestibule’s map and displays are clear. Louvre Abu Dhabi is a museum that wants to explore the concept of universalism in the 21st century and to do this from Abu Dhabi’s perspective, not from Europe’s, and in a manner in which all cultures are given equal consideration.

If the Grand Vestibule is an opening gambit that pays little respect to time or geography, the 12 galleries that follow unfold chronologically but in a manner that is no less theatrical, especially in their poetic arrangement of objects.

Dedicated to the emergence of the first kingdoms in the fertile river valleys of Mesopotamia, Egypt, South Asia and China and to the emergence of major empires in Mesoamerica, West Africa, the Mediterranean and Middle East, the early galleries display techniques that repeat themselves throughout the rest of the museum.

A long vista connects brooding statues from Sumeria and Egypt with distant figures from Classical Greece whose white marble shines in sunlight that pours through one the museum’s many picture windows.

Next, a gallery dedicated to the Hellenic world and ancient Rome begins with a monumental bust of Alexander the Great that helps to frame a colonnade of Roman busts that include several emperors.

As the aesthetic links between Greece and Rome become evident, the inclusion of an exquisite 3rd century standing figure of a Bodhisattva from Ghandara, in modern day Pakistan, not only illustrates the influence of Greek aesthetics on the iconography of Buddhism but also prepares the visitor for the next room, which is dedicated to universal religions.

It’s in this gallery, where a bronze Shiva from Southern India dances before a North Indian frieze featuring verses from the Quran, and Christian architectural relics provide a monumental backdrop to Malian ancestor figures and the contents of Buddhist reliquaries, that the museum’s blend of anthropology and art history really starts to become evident.

The effect is like the opening of some giant cabinet of curiosity whose contents are not only exquisite but whose display results in a form of visual and material layering that testifies to the past’s richness and depth.

It’s only at this point in the museum’s narrative, after four galleries of kaleidoscopic beauty and diversity, that Louvre Abu Dhabi delivers its first real disappointment.

Focused on long-distance Asian trade corridors such as the continent-spanning Silk Road and Arabia’s Incense Routes, which functioned as much as vehicles for the exchange of ideas as they did for commodities, Gallery 5 should have been the museum’s piece de resistance but sadly falls flat.

The period it covers witnessed the rise of the Tang and Abbasid dynasties, the advent of the Islamic Golden Age and the rise of Baghdad as a great world city alongside Chang’an, but sadly the richness, heterogeneity and intellectual dynamism of these centuries feels absent from the displays.

Certain objects stand out. A spectacular silver-gilt jar decorated with hunting scenes evokes the fertile mingling of cultures that occurred in Central Asia, but the layout of the cases in Gallery 5 and a preponderance of smaller objects in an oversized space leave the displays feeling simultaneously underwhelming and underpowered.

This unease continues in Gallery 6, which addresses the post-Roman history of a territory that once represented Rome’s empire, the Mediterranean basin and Europe’s Atlantic seaboard.

But despite the presence of some jewel-like late-Roman treasures including an exquisite bust of the Emperor Constantine (r.306-337) and an intricate gold medallion representing the Empress Licinia Eudoxia (422-462), a stately bronze Islamic lion (1000-1200) and Giovanni Bellini's luminous Madonna and Child (1480-85), the fine balance between the collection and the galleries only fully reasserts itself in the next wing.

As visitors enter a historical period that begins with the earliest advent of modernity, it’s entirely appropriate that Louvre Abu Dhabi’s discussion of the universal should reassert itself with a room dedicated to an expanded sense of the universe.

Around the end of the 15th century, enhanced mathematical and navigation skills allowed explorers to circumnavigate the globe for the first time, establishing direct links between cultures that had previously remained distant or unknown to each other.

The objects that fill Louvre Abu Dhabi’s modest intersection gallery, one of the many small annexes that supplement the museum’s main narrative, investigate these historical moments of first contact between Europeans, Arabs, Americans and Asians and the establishment of the global systems of trade that still define life today.

European globes are displayed alongside Islamic maps and treatises on nautical navigation including a 16th century copy of an earlier text Ahmad Ibn Majid, which has been loaned from the Bibliotheque National de France.

The pre-eminent Arab pilot and cartographer of the 15th century, Ibn Majid is believed to have been born in Ras Al Khaimah in the year that the Ming dynasty explorer Zeng He docked his ships in Jeddah. More than 60 years later, he was credited with helping to guide Vasco de Gama from Africa to India.

Ibn Majid’s text appears alongside early accounts of European encounters in South America that not only testify to the strangeness of those first contacts but chart the beginnings of the kind of Othering of indigenous peoples that informed European imperialism and colonialism.

Printed in Switzerland, Jean de Lery's History of a Voyage to the Land of Brazil, called America (1580), is illustrated with images of fantastical animals, demons and flying creatures, whereas a Dutch oil painting from just 75 years later shows Brazil subjugated and colonised, a place fit for the residences of sugarcane planters and their slaves.

In contrast, a gilded pair of 17th century paper Namban screens show Portuguese traders arriving on their black ships in the Sea of Japan, chronicling a moment when the power dynamics between the West and the East was very different.

The series of galleries that follow - charting the three centuries from 1500 - see Louvre Abu Dhabi achieve a level of compositional poise that is only matched by the treasures they contain.

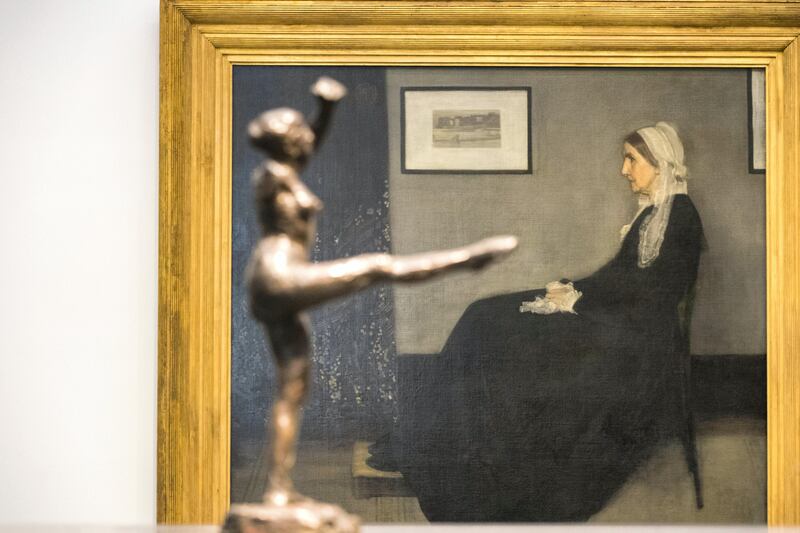

In the first, entitled The World in Perspective, the outstretched hand of Francesco Primaticcio's bronze Apollo Belvedere (1541-43), loaned from the Palace of Fontainebleau, manages to command a room that also includes Titian's Venetian masterpiece, Woman with a Mirror (c.1515), and the painting that promises to be one of the museum's masterworks, Leonardo Da Vinci's La Belle Ferronniere (1495-1499), both of which are loaned from the Louvre Museum.

The effect is the result of the kind of dramatic interplay between the statue and the museum’s lighting and architecture, a bravura performance that is repeated in each of the following galleries, where the visitor is greeted with a series of equestrian works that punctuate their narrative, each with the literal power to stop visitors in their tracks.

In a gallery dedicated to the influence of royal patronage in the Ottoman empire and Spain, Japan, France and Benin, Gilles Guérin's colossal Horses of the Sun (1665-1672) stands framed in the kind of light that would have once graced it in its grotto at the Palace of Versailles while Jacques Louis David's stupendous Napoleon Crossing the Alps (1802) forms the glorious finale to this particular enfilade of galleries.

Despite the grandeur, it’s also in these rooms where some of the museum’s quieter poetry can be found as well as the kind of subtle art historical flourishes that are easy to overlook.

The Guerin sculpture has been curated with great care, paired as it is with Jacob Jordaens' The Good Samaritan (1616-1615) and Laurent de la Hyre's Theseus Finding his Father's Sword (1639-1641), all three of which echo one another, representing a mini-study of the Baroque treatment of the human figure.

Meanwhile, in a nearby gallery dedicated to the art of war, the Horses of the Sun appears reflected in a glass case containing an ornate suit of French armour from the 16th century that stands opposite a suit of ceremonial Samurai armour, allusions that are entirely intentional but whose subtle visual layering must have been impossible to predict.

With only three galleries left, Louvre Abu Dhabi attempts to chart a new course for art historical discussions of Modernism and Modernity, Orientalism and Abstraction that begins with the advent of photography in the 19th century and then races toward the contemporary at a breakneck pace.

It is also in these galleries that the generosity of the French institutions who have provided Louvre Abu Dhabi with loans is most spectacularly evident and nowhere more so than in Gallery 10, where the Musee d’Orsay has provided its new stablemate with a series of masterworks that could form the nucleus of a world class museum collection in their own right.

The effect is dizzying as you realise that on just three walls the room contains major works by Manet, Monet, Caillebotte and Degas, Whistler, Van Gogh and Cezanne.

“There is just everything,” exclaimed one journalist, breathlessly, as they scanned the gallery walls trying to recover from the art historical equivalent of a sugar rush.

Unfortunately, there is a potential downside to such largesse. Displays like the one delivered in Gallery 10 are sure to attract criticism and accusations that Louvre Abu Dhabi’s displays represent little more than humanity’s greatest hits, but as even the works in these busy final rooms suggest, something more profound is also taking place.

Acting as a counterbalance to its A, B, C of Impressionism, Gallery 10 also contains Orientalist works by Delacroix and prints by Hokusai and Hiroshige alongside the work of Gaugin that they directly influenced. There is also a large central display dedicated to sculptures from Africa and Oceania that are celebrated, not just for the influence on the development of European Modernism, but as major works in their own right.

As is the case with all of the museum’s galleries, an added layer of interpretation and narrative is applied to the gallery in the form of the animated display that greets visitors as they enter, in this case discussing the role of Universal Expositions as platforms for exhibition and cultural exchange.

If Gallery 10 fails to provide any art historical surprises, Gallery 11: Challenging Modernity builds on more recent scholarship, exhibiting masterworks by Mondrian and Picasso, Rothko and Pollock alongside works by the UAE’s Hassan Sharif, the celebrated Cuban artist Wifredo Lam and the Sudanese painter Ibrahim El-Salahi.

The overly busy hang in Gallery 11 sets out to explore Modernism's global effervescence from a multi-polar perspective in a manner that echoes recent major international exhibitions such as the Okwui Enwezor-curated Postwar: Art Between the Pacific and the Atlantic, 1945–1965, which opened at the Haus der Kunst in Munich in 2016 as well as recent surveys of Sudanese Modernism at the Sharjah Art Foundation and major retrospectives of Lam and El-Salahi at London's Tate Modern.

The problem here is that there is simply too much work and not enough space for a subject that will eventually fall within the remit of the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi, whose mission is to decouple art history from its traditional Western bias.

In the final gallery, A Global Stage, and outside in the museum’s courtyards and precincts Louvre Abu Dhabi’s displays resume the dialogues between the art and the museum’s architecture that encapsulate its most enduring effects.

Ai Weiwei's chandelier-like Fountain of Light (2016) reaches up to one of Jean Nouvel's skylights, while paying an ironic tribute to Vladimir Tatlin's Monument to the Third International (1919-20), a 1,300-foot-high love letter to the achievements of Bolshevism that was planned for St Petersburg but never realised.

The result is the fusion of three visions of utopia that represent humanity’s past, present and potential future.

The narrow, European model of the Enlightenment may have failed and China’s current combination of Communism and Confucianism may yet to be proven, but Louvre Abu Dhabi’s model of universalism, which celebrates the beauty that connects all humanity, is surely a vision that deserves our support and consideration.

Post-imperial, post-colonial, multi-polar and yet unmistakably French, the museum is a triumph that could only have been achieved in a place such as Abu Dhabi, a young country where ambition and optimism refuse to be limited.

__________________

Read more:

[ Louvre Abu Dhabi: The museum of then, now and the future ]

[ Louvre Abu Dhabi opening: everything you need to know ]

[ Louvre Abu Dhabi opens membership programme ]

__________________