Three Brothers is Peter Ackroyd’s first novel in four years and, according to a recent interview he gave, something of an escape from his non-fiction projects. These, of course, are what he remains most famous for in recent years – his histories of London and biographical accounts of certain celebrated literary figures and their relationship to the city they wrote about – Wilkie Collins, William Blake and Charles Dickens, to name a few.

There are elements of each of these writers’ works in Three Brothers – it’s something of a bildungsroman, a ghost story, and a murder mystery, all rolled into one. Not to mention, a novel in which coincidence and chance play central roles. In short, a novel very much about London. Or Ackroyd’s London, at least – a city he sees as seeped in its own rich history, a history that engulfs its inhabitants at every turn, drawing them into a thick, tangled net of connections.

Ackroyd’s story begins on a post-war council estate in the London borough of Camden. Three brothers – Harry, Daniel and Sam Hanway – are born with a year’s difference between each of them, but are “united, however, in one extraordinary way”. They all share the same birthday, May 8, on which each was born at precisely midday on three consecutive years. Their father is a night watchman, then lorry driver, a man of ironically few words considering the literary aspirations he once harboured as a youth, before he became a slave to the responsibilities of marriage and fatherhood. Their mother exits early on, disappearing one day without any explanation when her youngest son, Sam, is still only eight. Their father proffers no explanation, and never speaks about her again.

Marked by some “natural affinity”, the paths each of the brothers take through their lives diverge early on, the gulf between them widening as they grow older, though ultimately their fates remain oddly entwined. Harry, the oldest, leaves school to work as an errand boy at the local newspaper where he proves himself a quick and clever learner of the profession – soon promoted to reporter, then winning a competition that lands him a job in Fleet Street at the tender age of18, where he then continues to climb the greasy pole of success. Daniel, meanwhile, is a scholar and bookworm. A snobbish young man with nothing but “disdain” for his family and upbringing, he works hard at his “Orwellian” grammar school – “It’s all so Kafka-esque,” he and his friend complain to each other – before going up to Cambridge and the life of academia that follows. Sam, however, is the odd one out, a lonely, melancholic child, apparently possessing none of his brothers’ drive, ambition or intellect. He doesn’t do well at school, nor any better in the grocer’s shop where he gets his first job, and after he’s fired he spends his days aimlessly wandering the city, people watching in the parks and helping in the garden of a local covent.

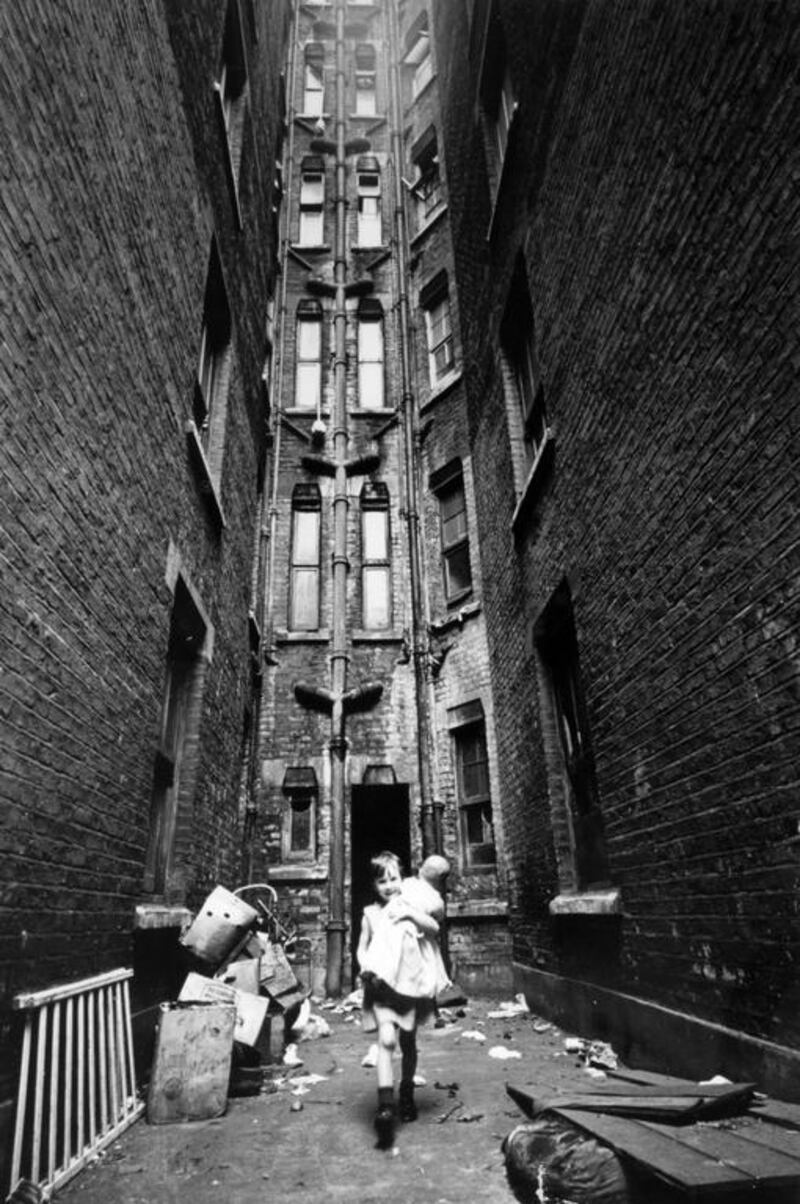

As the years go by, the brothers drift in and out of each others’ lives, sometimes passing each other in the street, sometimes only linked by the third parties they have (often unbeknownst to them) in common. Ackroyd’s vision of the city is extremely similar to Dickens’ in this respect – everybody is connected to everybody else in some way, and these tendrils of association reach from the heights of the corridors of Westminster and the world of power of the newspaper and publishing house owners, right down to the slums of South-east London with its petty thieves, prostitutes and paupers. “That is the condition of living in a city, is it not?” Daniel puts to an undergraduate who questions the “continuing use of coincidence” in Dickens’ Bleak House: “The most heterogeneous elements collide. Because, you see, everything is connected to everything else.”

The story that brings the characters together revolves around the central figure of Asher Ruppta, a slum landlord we can assume is loosely based on the real-life figure of Peter Rachman. As an intrepid young hack looking for a story, Harry is the first of the brothers to encounter Ruppta. He’s eager to expose the man’s dodgy dealings, but the powers that be have associated skeletons in the closet that they need to keep hidden, and he’s forced to kill the story. Daniel, it later turns out, is sleeping with one of Ruppta’s tenants – a male prostitute, some of whose clients turn out to be men in powerful places and thus with their own secrets to keep. While, last but not least, Sam eventually gets a job as one of Ruppta’s rent collectors.

During the Bleak House tutorial, Daniel explains to his undergraduate that in most of Dickens’s novels, “the city itself becomes a form of penitentiary in which all of the characters are effectively manacled to the wall. If it is not a cell, it is a labyrinth in which few people find their way. They are lost souls.” So too, Ackroyd’s own characters scrabble around the often seemingly maze-like streets of the city, alone and isolated even as the broader populace mills around them. Each of the boys sees apparitions of various sorts in the course of the novel, the ghostly vestiges of their and the city’s pasts. Sam suffers from the most vivid manifestations, the ovent where he works for many months, helping the nuns with their garden and feeding the homeless, just suddenly disappears one day. No real explanation is given for this dip into the supernatural, but it’s as if the boundaries of history have been breached, allowing Sam to slip into the past for a brief period of respite from problems in the present that threaten to overwhelm him.

Ackroyd traverses every corner of the city, from the “peeling stucco and the untidy balconies” of 60s rundown Notting Hill; foggy, dark, damp streets down by the river in Limehouse; dusty pubs in Hackney and Borough; the bastions of traditional wealth and privilege, Chelsea’s Cheyne Walk and the streets of Mayfair, versus the gated, modern houses of Highgate; to seedy, bohemian Soho. At one point, Daniel is asked to write a book about London writers, a theme of which becomes, “the patterns of association that linked the people of the city; he had found in the work of the novelists a preoccupation with the image of London as a web so taut and tightly drawn that the slightest movement of any part sent reverberations through the whole. A chance encounter might lead to terrible consequences, and a misheard word bring unintended good fortune. An impromptu answer to a sudden question might cause death.” Ackroyd’s plot hinges on similarly slight, but consequential, movements, and it’s coiled as tight as a spring, admirably so, but sometimes the story seems to press forward at such speed, I wanted to linger a moment longer in the dingy side streets, or in the crowds amongst a publishing party, just soaking up the atmosphere. No contemporary author writes about London with as much verve as Ackroyd, though, he’s master of the city’s soul.

Lucy Scholes is a freelance journalist who lives in London.