The first flowers to bloom in Russia after the harsh winter are pale yellow, and their appearance signals the start of spring. The word primrose loosely translates in Russian as "first colour" and is the title of a remarkable new exhibition of 100 years of Russian colour photography from the late 1800s to the 1970s. "Like the sun arriving on the Earth," notes the curator Olga Sviblova.

The exhibition at the Photographers' Gallery, London, explores how Russian photography evolves from visual documentary to propaganda tool and, finally, into a subversive art form during a century of political and social upheaval.

Primrose opens with photographs that were tinted by hand with watercolours. The early images are mainly portraits, but also expanded to include architecture, landscape and industrial themes.

The power of photography was quickly grasped by Tsar Nicholas II, who then dispatched a leading photographer to document life across the empire. This is the subject of the second part of the exhibition.

Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky travelled from the steppes to the Causcasus to make a visual record of a life that was rapidly coming to an end.

"We get a sense of just how vast and diverse the Russian empire is," says Sviblova.

"We can see all the different parts. We can see Crimea. We can see Georgia. We can see Siberia. We can see the different styles of life. It was a Russia that was open to Europe."

These photographs are placed alongside the autochromes of Pyotr Vedenisov, whose images show the lifestyles of Russian elites.

Then came war.

"The first world war changed everything. This type of colour photography was stopped and in 1917, the revolution came. This marked the start of the nationalisation of photography and as a medium for propaganda," says Sviblova.

The Bolshevik revolution and civil war brought chaos. Many of the promised reforms and improvements had not materialised and the majority of the population lived in poverty.

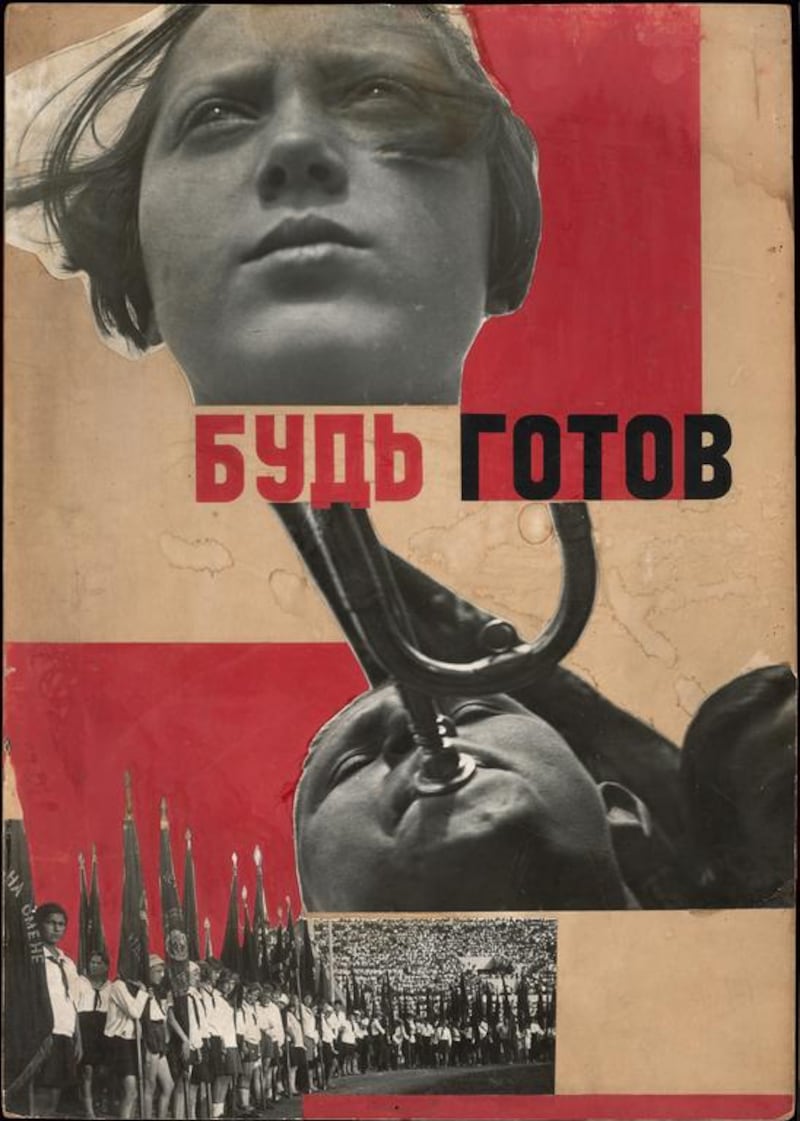

As most people could not read or write, authorities used photomontage - where several photographs are spliced together - as a propaganda tool during the 1920s and 1930s.

"It was used by them to construct the type of Russia that they wanted people to see."

This meant, says Sviblova, who founded the Moscow House of Photography in 1996, that they created visual utopias - utterly at odds with reality - and the colour red became dominant.

However, even this control of photography was not enough for Stalin. After the Second World War, the Soviets, taking the technology from the Germans, built their own factory to produce costly colour film. During this time, from the 1940s to the early 1950s, only a select number of official Soviet publications were permitted to use colour photography.

And even then, the use of the medium was solely to reinforce rigid Stalinist doctrine.

Photography at this time, according to Sviblova, was in the service of the ideological machine.

"Everything moved by the decision of the Communist Party. Stalin's regime found you everywhere and you could not be free - even in your own apartment."

But when Stalin died, a new era began.

"The 1960s ushered in the start of the Khruschev spring. Thousands arrived back from Stalin's prison."

This Khruschev Thaw from the late 1950s to the early 1960s resulted in some of the repression of Stalin's years being reversed and a new type of humanistic photography emerged.

This new phase of vibrant photography was particularly evident in the street scenes of Dmitri Baltermants.

Born in Warsaw in 1912, Baltermants's father had been killed while fighting with the Russian army during the First World War.

Baltermants was originally a maths teacher, but switched to photography and became a Kremlin photographer, covered the Second World War and was twice wounded during the battle of Stalingrad.

But the Khruschev period allowed Baltermants the freedom to experiment.

He developed an eclectic style and showcased his artistic range with powerful street photography, including one particularly striking aerial shot of people standing by a tram during a rain shower.

"This became a time when the photographer could show real life. We had this moment of freedom in general and in Russian photography particularly - real life, real human faces and how people lived.

"Under Stalin, it would have been impossible to show this type of everyday life. The people smile, they look more sympathetic. The real life, a social life was reflected. Russian colour photography was now open to the world."

But the story does not end there. Another phase developed in the 1970s, when Leonid Brezhnev was in power.

Brezhnev sought to roll back many of the liberalising reforms and clamp down on cultural freedoms that his predecessor had enacted.

This resulted in the resurgence of hand-tinted pictures, driven by a nostalgia for the past and to reflect the stalled progress of the Soviet Union.

This period also witnessed the emergence of slide shows. Colour film became more available to the public and underground photographers showed their work in apartments, private clubs and studios to like-minded people as a way of challenging the Soviet narrative.

This represented, Sviblova notes, the parallel life that many people lived at this time.

"In the 1970s, an underground culture developed. It was an unofficial culture, an underground culture in the Soviet Union. People lived a type of private life."

John Dennehy is the deputy editor of The Review.

. Primrose: Early Colour Photography in Russia runs until October 19 at the Photographers Gallery in London.

jdennehy@thenational.ae

London exhibition explores 100 years of Russian colour photography and its highly politicized usage

In the former Soviet Union, photography was used as a powerful tool of propaganda, with only a select few publications allowed to use colour photos. A new exhibition on Russian colour photography is currently showing in London.

Editor's picks

More from The National