"When I work on a record I don't only want to give people the music, but also the context of where that music comes from," says Samy Ben Redjeb. "For me, it's relatively easy to put together a compilation that's solid, but that's just the tip of the iceberg. I want to find the musicians, interview them, write about them and tell their stories."

Over the past seven years, Analog Africa, the Frankfurt-based label he runs, has released a series of expansive, lavishly annotated collections of hard-to-find music from across the continent. Kicking off in 2006 with the soaring, polyphonic guitars of Zimbabwe's Green Arrows, the imprint's catalogue now covers eight countries, from the hard-driving voodoo-funk rhythms of Benin's Orchestre Poly-Rythmo de Cotonou, through "mystic soul" from Burkina Faso and an effervescent sampler of dance floor fillers produced in Angola between 1968 and 1975.

Today, however, Redjeb is talking about his latest project: Afrobeat Airways 2: Return Flight To Ghana 1974-1983. This latest installment of what looks to be a continuing project travels across the West African nation, including tracks by the singer K Frimpong, The Cutlass Band and lesser-known talents, such as Uppers International and the delightfully named Los Issufu and His Moslems. True to the label's ethos, it is accompanied by a 44-page booklet, featuring an introductory essay by the music critic Banning Eyre, plus Redjeb's own artist interviews and historical research.

Born to a German mother and a Tunisian father, 42-year-old Redjeb clearly relishes the globetrotting lifestyle the album's title evokes. In fact, it was while working as a diving instructor in Senegal in the early 1990s that his love affair with African music began. "I had never heard anything like the music I was hearing while I was living there," he says. "I used to visit the markets and buy tapes all the time. I left when my work permit was up, but then I realised how much I loved being in Africa and how much I missed it."

Redjeb soon found a way to return, picking up a job as a hotel DJ in the town of Mbour, about 90 kilometres south of Dakar. "I didn't have much experience, but I thought I'd give it a try," he says. "My audience was mainly tourists, so I started out playing house music, hip-hop and pop songs for them. Then I thought that if people were visiting Senegal, they should at least hear some music from there. I spoke to the hotel manager about putting on a weekly African party. He really liked the idea, and gave me a driver and some money to go out and buy records."

Gradually, Redjeb built up a thriving club night that attracted holidaymakers and, most importantly, a knowledgeable local crowd. "It grew and grew over time," he says. "There were Senegalese workers in the hotel and they started to come to the party. They told their friends and their families about it and then they started coming, too. Being in contact with so many Senegalese people in that setting, I was getting a lot of advice from them about all kinds of different music that I should be playing – bands that you had to dig a bit deeper for like Number One du Senegal, Étoile de Dakar, Orchestre Baobab and Le Sahel. That was when my musical education started." After leaving Senegal, Redjeb took a job as a flight attendant with Lufthansa that allowed him to purchase discounted flights back to Africa. This perk would prove invaluable in the early days of establishing a boutique record label specialising in rare music from far away. "Back then I was flying into Accra a lot because I could do it very cheaply," he says. "From there I was often going on to Benin, where I was doing a lot of my work at that time. Because I was stopping over in Ghana for a few days each time I made the trip, I got to know musicians there, but I didn't want to do a compilation on the country. It was a well-known place for music, so [it] had already been covered very well by other labels and I didn't think that I could do a better job than them."

A few years and a misplaced passport would change that. "I had planned to go to Angola, but I missed my flight and couldn't get another one because they were fully booked for two months," says Redjeb. However, it turned out that the airline in question was happy to give him a trip to Accra as soon as he could travel again.

"I had friends there, so I thought, why not. When I arrived I met up with my friend Dick Essilfie-Bondzie [producer, head of the independent Essiebons label and the man who discovered artists including the highlife star C?K Mann]. He told me that he was going to start up his label again. He also said that he had digitised all his tapes and gave me some music to listen to. When I played it I heard all these great unreleased songs, so I went to him and said that we should make a compilation. That's how the first Afrobeat Airways came together."

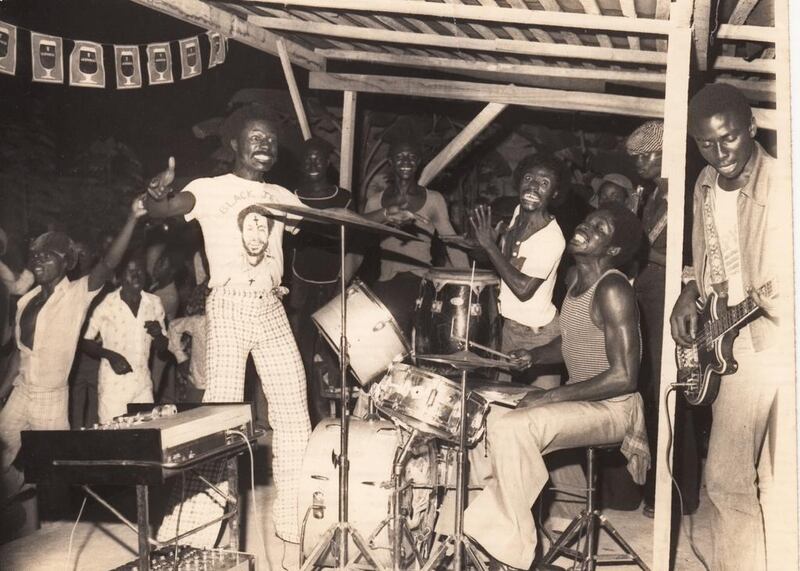

While Analog Africa's second Ghanaian collection was slightly better planned, it still benefited from a certain amount of serendipity. While scouring Accra for music, Redjeb had learnt much about the city's pop cultural past. During the 1970s, the TipToe club was one of the most important live music venues in the capital and famous for huge dance competitions and beauty pageants. Directly opposite sat the Modern Photo Works. The studio's late owner SK Pobee spent years documenting Accra's music scene: young dancers cutting loose at the weekend, local heroes in full swing and visiting stars such as Fela Kuti commanding the stage.

Finding out that the store still existed and was run by Pobee's son, Redjeb asked his contacts to arrange a meeting. When he arrived, the owner was somewhat bemused but presented him with a box of roughly 400 prints and negatives salvaged from a flood that had destroyed most of the archive some years previously. Thanks to hours of work by Redjeb, many of these images can now be seen, some for the first time ever, in the booklet for Afrobeat Airways 2.

"After some negotiations, I was allowed to take the negatives home with me to scan, then send them back later," says Redjeb. "When I saw them in the shop, I couldn't really tell what they were, but when I started to digitise them, I gradually began to realise just how important this guy was. He had managed to photograph everyone who played at the TipToe because he was the club's photographer, but he had also been everywhere else in town and all around the country, too.

"People around the world know about Malick Sidibé from Mali who did something quite similar, but there were other Sidibés in Africa and I think that I have found one of them. I think now that my next project is going to be a book bringing together all of those images and showing what life was like in Ghana at that time. What I really want to do is make S?K Pobee's work known."

Dave Stelfox is a photographer and journalist. He lives in London.

Labour of love

The latest offering from a German record label owner who travels all over Africa searching for vintage musical gems features brilliant tracks recorded in Ghana between 1974 and 1983, writes Dave Stelfox

Editor's picks

More from The National