Shortlisted work for the Jameel Prize 2011 will go on display at the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) in London on July 21. The winner is to be announced in September, but even before that, an agenda and narrative beyond the typical parameters of an art prize have emerged.

Rather than deconstructing a conceptual conundrum or focusing on the hazy boundaries of regions and place, the exhibition of artists nominated for this year's prize — touring Europe and America over the next few months — examines something more tactile.

Simply put, this is a celebration of the handmade. There are 10 artists shortlisted for this year's £25,000 (Dh147,180) biennial award for contemporary art and design inspired by the Islamic tradition.

Each artist responds to what Salma Tuqan, a curator in the V&A's Middle East department, calls an engagement with "Islamic craft, art and design", noting that such processes have played an intrinsic part in art from the Islamic world.

"The Jameel Prize is not solely about contemporary art," Tuqan says, "but about the craft element and opening the viewer's eyes to what constitutes Islamic art."

Much of what we might refer to as "Islamic art" are objects that are as useful and functional as they are aesthetically pleasing. This spans illuminated religious manuscripts, ceramics, mosaic and textiles through to architecture and its ornamentation. Often, works of "Islamic art" are less for contemplation in themselves than for use as tools that awaken and heighten a sense of contemplation in the viewer. Calligraphy - a means of artfully communicating lines or even a single word from the Quran - sums this up perfectly.

The shortlist has been selected by key players in the Middle East's art scene, including the 2009 winner, Afruz Amighi. Some nominated artists are familiar names - the likes of Monir Farmanfarmaian, a key figure in Iranian art who creates stunning mirror mosaics, and Hayv Kahraman, here turning her nuanced style of painting solemn, ethereal female figures to creating a deck of playing cards that depicts the lives of Iraqi exiles.

But there is ample space given to more emerging talent. Noor Ali Chagani, for instance, applies the intensive education in miniature painting he gleamed from Pakistan's art colleges and applies it to tiny terracotta bricks. With the same intricacy and exactitude of this Mughal style of painting, normally reserved for illuminating religious texts and poetic epics, Chagani hand-fires thousands of these small bricks and mortars them together to create an undulating form.

Despite the hardness of the material, the sheer number of bricks, like the tiny dots of paint found in miniatures, creates a knitted-together impression. A mass of terracotta appears as malleable as crumpled silk in the hands of the miniaturist.

Yet no artist takes his or her inspirations literally. Instead, we see sensitive subversions, and interrogations of craft forms. Aisha Khalid - another Pakistani artist in the shortlist - examines the tradition of weaving in rural Kashmir. Khalid worked with the women of communities there to create a pashmina shawl, but subverts this by piercing the material with long, gold-plated pins. On one side of the pashmina, only the delicate paisley pattern is visible - flashing with the gold of the pinheads. On the other, the steel shafts of the pins protrude to create a menacing reverse: a nod to the violence that underpins life in this contested borderland.

The hook in the Jameel Prize is this emphasis on making; it offers a refreshing alternative to an increasingly concept-driven landscape of art prizes. Process, and the idea that an artist should roll up his or her sleeves and engage with a craft hands-on, seems to be a key feature of the work that has made it into the final lineup.

In this way, Bita Ghezelayagh has developed a near-obsession with felt. She trained as an architect in Paris but returned to Iran at 28 to find the country of her memories irretrievably lost. The traditions and nuanced way of life she'd longed for while away seemed to have been brushed away in the cumulative carnage of the revolution and the Iran-Iraq war of the 1980s.

"It was all about girls having blonde hair and nose jobs all of a sudden," she says. "When I came back there was no value for traditional Iranian things; the elements that were valued in my youth."

She found that craft had been one of the first things to go. "The value of handmade simply vanished in my country. It was very upsetting for me." She began an odyssey across the country to understand felt - a cheap material at odds with the strange, outward-looking idea of glamour that she believed had consumed Iran's young people.

"I was fascinated by the Turkomen of the north of Iran," she says. "I started felt-making with the women there about eight years ago. When I'd finished my first piece, it shrank and was full of holes and wasn't good even for using as a rug on the floor. But I looked at it and thought that it could go on a wall because it was so beautiful."

Ghezelayagh's shortlisted pieces develop this approach. She uses felt to recreate the dress-like garments once worn in battle in old Iran. These once had a talismanic quality, thought to provide spiritual protection on the battlefield. But the artist says the material itself was a sort of talisman for her: "Felt is a very mystical material for me. It's often worn by shepherds, and the Prophet himself was a shepherd."

Learning the old forms of dressmaking found in Iran, Ghezelayagh has woven the slogans chanted in the early days of the Iranian revolution into the garment, along with metal keys, a reference to the key to Paradise promised to young men who died during the Iran-Iraq war. She describes the work as borne of her "guilty conscience" for having been out of Iran then, but says it is also for the friends she lost in that war.

As two visual cultures overlap in the work - of ancient talismanic dressmaking and the emblems of the revolution - new meaning for both is created. Old techniques are given a contemporary relevance; a line of continuity - even if it is conceptual - is struck between the two.

Similar juxtapositions fire the work of Babak Golkar, an Iranian who has spent much of his life in the US and is shortlisted for a series of sculptural works, Negotiating the Space for Possible Coexistences. He refers to the collision of forms and the subsequent creation as "alchemy".

Golkar has taken the abstract patterns woven into a carpet by nomads in Tabriz and imagined them as blueprints for a city. Laying three-dimensional sculptures of skyscrapers on top of the carpet, the buildings seem to sprout from the carpet itself. Yet, when viewed from above, these gleaming white structures disappear back into the pattern of the rug.

"When you realise that these works can collapse from the top down into a carpet and vice versa then there's a moment of alchemy and realisation in that," says Golkar. "But there's alchemy also in a sense of the blending of two dimensions and three dimensions - putting them together and seeing what the outcome is - and also a binding of a modern or post-modern cityscape and that of the nomad."

The works implicitly reference the gleaming new cities of the Gulf in their appearance. "It's not necessarily a critique," he insists. "It's really brushing against this idea of these massive developments which could be irrational, at times - especially if you view them from above.

"Take Dubai's Palm Island: it's consciously made to be viewed from above - but who has that point of view? Either those flying over, or God. That relationship between our gaze and a metaphorical eye overlooking us is what interests me here."

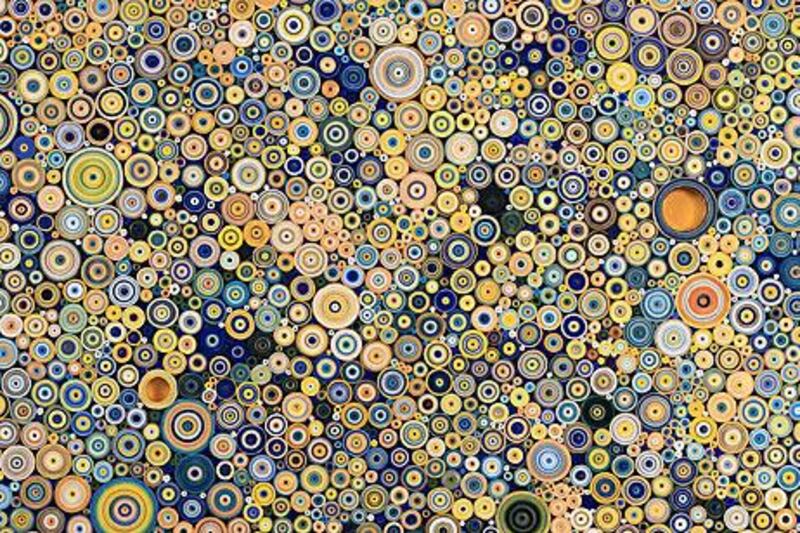

Though only its second time around, the Jameel Prize is staking out a clear territory. In placing craft and design at the heart of its criteria, it suggests that connections with an often overlooked wealth of Islamic art history can be made when considering contemporary art coming out of the region. It offers a good reminder that art history was fired in kilns, painstakingly woven or daubed in workshops and assembled from a scatter of influences like the surface of a mosaic.

The artists shortlisted for the Jameel Prize 2011 are Noor Ali Chagani, Hadieh Shafie, Soody Sharifi, Hayv Kahraman, Rachid Koraichi, Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian, Aisha Khalid, Bita Ghezelayagh, Babak Golkar and Hazem El Mestikawy. The exhibition opens on July 21; details at www.vam.ac.uk.