The labyrinthine complexities of film financing can be hard enough to grasp for those inside the industry, let alone those without experience of movie production or degrees in creative accountancy and entertainment law.

Nonetheless, you might imagine that for a low-budget film with a big-name cast, a solid director in Eric Styles (Relative Values), and which has already completed shooting and simply needs top-up funding for post-production, surely the process should not be too difficult?

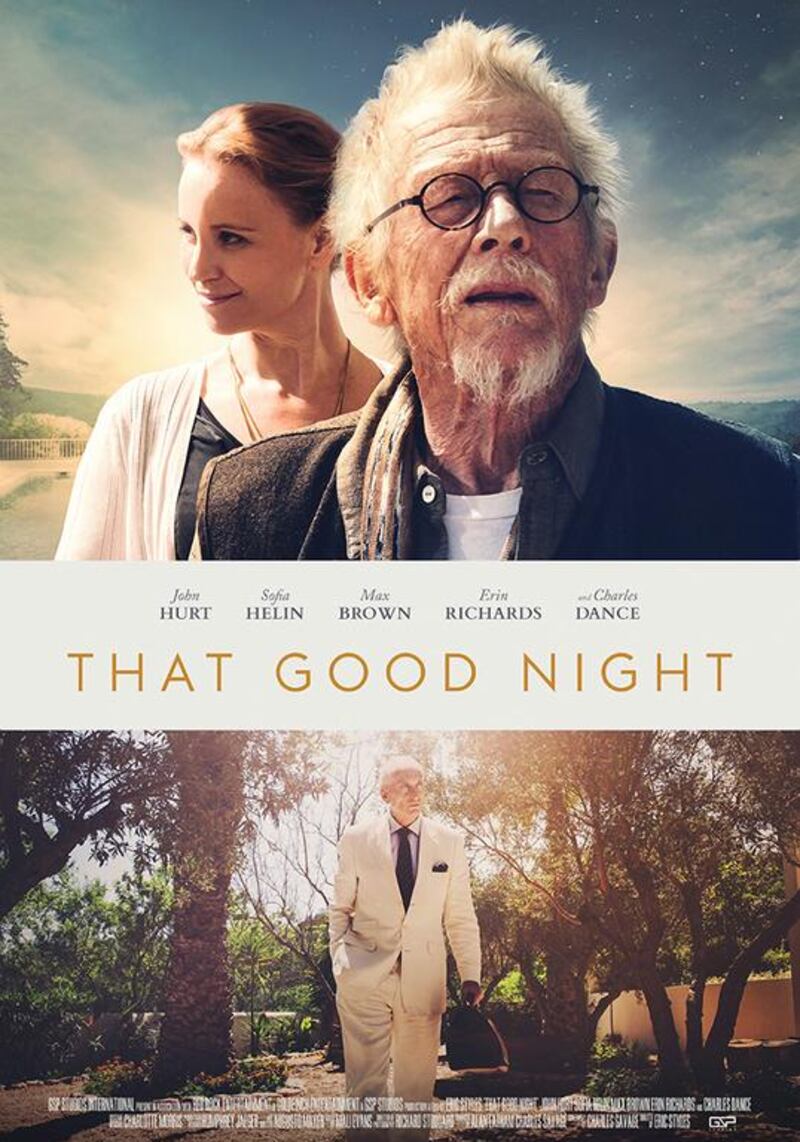

On the basis of that cast alone – including John Hurt (in his final role before his death in January), Game of Thrones star Charles Dance, Erin Richards from the TV Batman prequel Gotham and Max Brown, who has appeared in Marvel's Agent Carter and The Royals – you might imagine the producers of That Good Night would have no shortage of potential investors.

Not so – the filmmakers launched an online appeal, which closed last month, to attract completion funding.

Executive producer Charlie Wood explains that a few acclaimed actors do not necessarily guarantee easy access to funding.

“Not always,” he says. “As familiar as most people are with films, the actual film-investment arena is new to most people. And because of this, many are reluctant to venture into unchartered waters.”

While big-name directors such as Steven Spielberg and J J Abrams might be able to walk into a studio and leave with a blank cheque, Woods says this method of crowdsourced fundraising is remarkably common, even at a relatively high level in the industry.

This is the seventh film for which he has raised funds this way – in the past 18 months alone he has received about £5 million (Dh23m).

“Marketing online offers much greater flexibility regarding who we are able to market our film investments to,” he says. “We are able to get in front of a well-profiled audience, or high-net worth individuals with an interest in film.”

Filmmaking, however, is a notoriously risky investment. It is an oft-repeated fact that the big studios rely on the huge profits from about 10 per cent of their films to offset the losses from the other 90 per cent. So why would anyone take the chance when there must be safer investments?

“The tax breaks can be excellent for taxpayers in the United Kingdom,” Woods explains.

“The UK government offers something called an Enterprise Investment Scheme. Anyone paying tax in the UK may be eligible for an income-tax rebate under the EIS. Essentially, British taxpayers are allowed to claim back 30 per cent of the amount that they invest into an EIS film investment.”

Tax is not an issue for investors in the UAE. Schemes such as Abu Dhabi’s 30 per cent capital expenditure rebate for productions that film in the emirate offer a similar incentive.

Hasnain Khalid is a lawyer who has represented MGM in the UK, singer George Michael, pop mogul Simon Fuller and a host of Pakistani production companies. He also served as an adviser to former Harrod's owner Mohamed Al Fayed when he was funding Unlawful Killing, a controversial 2011 documentary about the death of his son Dodi and Britain's Princess Diana in a car crash in Paris in 1997, which failed to secure a release in any major territories over litigation fears.

Khalid is well-versed on the tax benefits of movie investment for aspiring co-producers in the UK. The US industry, he notes, is much less likely to use investors without existing links to the movie world.

“The [UK] government has tightened up a bit now, but the tax situation used to be a nasty piece of work,” he says.

“Investors were basically investing in rubbish and banking on it being a financial disaster, so they could claw their losses back against tax they had paid. I heard recently of just one single film project that the Inland Revenue was trying to get back £800m from.”

The previous tax situation did at least provide some amusing anecdotes for the lawyer. “I remember one investor who had put a fortune into what they thought was going to be a terrible flop,” he recalls.

"I was at the screening and their face went white – it turned out to be Atonement with Keira Knightley. You could see their horror when it turned out to be a good film they might actually make money on and have to pay even more tax."

Not everyone investing in film is doing it to avoid tax, of course. Khalid identifies two other main types of investors.

“Some are just hard and fast investors,” he says.

“You’ll get your money, but they want their returns, and the sooner and the more the better. That can be a bit of a disaster when it comes to contact with creatives.

“It always amazes me, with film in particular, how little forethought goes into projects. You may be a highly creative director, but you have to sit down with lawyers, with accountants. The days of winging it are long gone.” The second type is a little less cut-throat.

“Others just like the idea,” says Khalid.

“Like in the old days when a rich individual would sponsor a painter for the prestige and the philanthropy.”

Khalid admits he would be hesitant to invest in a film. “I’m not sure I would, unless you absolutely know it’s going to be a success, which you never do,” he says.

"When I was at MGM, the head told me that George Lucas had come to him with Star Wars in 1974 and he thought he was mad: 'These clunky little models pottering around in space? 2001 was already a commercial failure. Who's going to be interested in that?'"

Well, nobody is perfect.

Ayesha Chagla heads Dubai Film Market, the industry arm of the Dubai International Film Festival, one of the region’s biggest hubs that brings filmmakers and investors together.

She says there are three main types of non-industry investors in this region – the first two of which align closely with Khalid’s observations.

“People who are genuinely interested in film as a way of diversifying their portfolio, and see it as a genuine investment they expect returns on,” she says. “And people who will do it as a philanthropic move – fortunately a lot of people in the region want to support regional artists.

“The third is the type of person who just likes the idea of being on the red carpet and the glamour side.”

So what should you bear in mind about the pros and cons of investing in film before handing over any cash?

You might be seeking glamour, you might be interested in that warm glow of philanthropy, or you might have your eye on the luxury pool, the limo and big-name Hollywood stars and producers on speed dial.

It is a favourite mantra of Image Nation chief Michael Garin, repeated and disputed in equal measure by his many disciples in the local industry, that “it’s called show business, not ‘show’ show” – a reminder that the bottom line is that the numbers have to add up.

Whether you are an aspiring director seeking funds, or an investor interested in providing them, you need to identify your reasons and what you want to get out of it.

Get the right advice and be aware that in a high percentage of cases, particularly with foreign-language indie films, riches and global prestige may be a long time coming.

cnewbould@thenational.ae