Finally, after years of ruling an independent-minded country, after thousands of citizens took to the streets to demand his departure, after a long rule that polarised public opinion and set the north against the south, a tough billionaire leader of a sun-drenched country has agreed to step down. Sadly, that leader was not Yemen's Ali Abdullah Saleh but Italy's Silvio Berlusconi.

Ten months on, Yemen's uprising is still ongoing, still bloody, with no clear end in sight, the longest of all the Arab uprisings. Tens of thousands have taken to the streets, all across the country, a size of popular resistance unmatched in any Arab country bar Egypt.

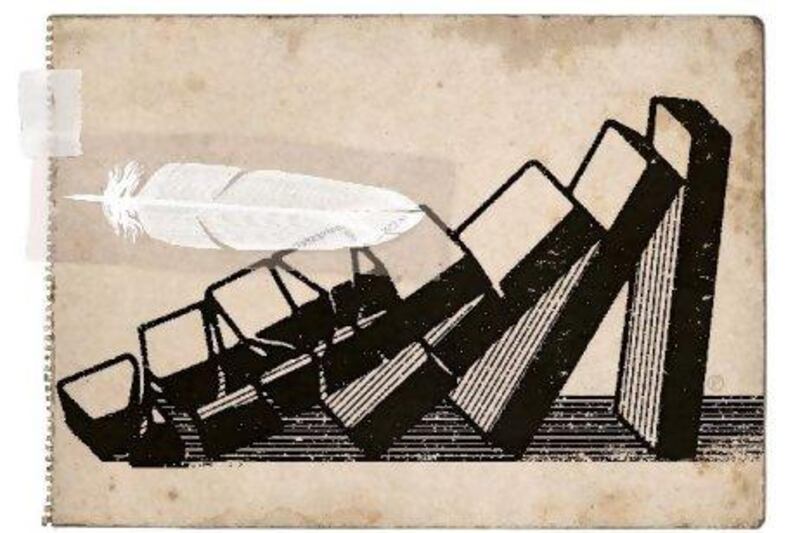

Of the three Arab leaders that have resisted the winds of Arab change these past few months, Yemen's leadership remains the only one to escape serious international censure. That may soon change. If it does, the dominoes may begin to fall and Yemen may shift to a new future. But what type of future?

This week, Ali Abdullah Saleh promised in a television interview that he would step down. Yet that possibility now seems more remote than before. Listening carefully to the president's words in the interview, it is clear that Saleh envisages many hurdles before that time: he would only leave after an agreement on the GCC initiative has been reached, and that agreement signed, and a power transfer agreed, and elections occur.

Given that Saleh has come close to signing the agreement before, and that an agreement was reached for his prime minister to assume the power to call presidential elections, it seems unlikely this is a serious offer.

Syria and Yemen are incredibly complicated countries: Syria externally, because of its geographical position and regional alliances; Yemen internally, due to its complicated web of politics. It is this complexity that makes any movement by international actors so risky.

For a start, the political parties of Yemen have not been as clearly co-opted by the regime as Syria's - the country has had democratic institutions and elections for some time. There is a political opposition but, like the opposition to Ben Ali's rule in Tunisia, years of making accommodations with Saleh and his ruling General People's Congress party have tainted them in the eyes of most citizens. When the Arab Spring swept across the country, the official opposition, the Joint Meeting Parties, were left scrambling. For many Yemenis, such parties offer only incremental change in a stagnant political system, rather than the wholesale reform the protesters are demanding.

There is a second layer of political power, the fluid grouping of elites that have helped and hindered President Saleh at various times, while enriching themselves. These are chiefly the Al Ahmar family and a former close ally of Saleh, General Ali Mohsen, who defected from the president's side at the height of the protests. It is likely both of these groups will try to capitalise on the instability to increase their power.

Into this equation comes the southern independence movement. Since unification in 1990, what was South Yemen has sat uneasily in the union. The south has fewer people and most of the country's wealth, yet the years of unification have seen a gradual slide of economic and political power away from the south. As the protest movement has continued without resolution, some southerners have begun to grumble that it is time to move away from the protest movement and push for independence.

The final part of this tapestry is the best known, the eclectic and energetic youth movement whose protests have gripped the country for the past 10 months. In Tawakkol Karman, the journalist and activist who was last month awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, the movement acquired a powerful new spokeswoman, one with international recognition. It was after a meeting in Paris last week with Karman that France's foreign minister first mooted the idea that Saleh's assets might be frozen, suggesting talks on that move would take place this week among European leaders.

So far, the loose alliance of youth protesters, southern secessionists and Saleh's political rivals has not been sufficient to force the resignation of the president. External actions, either by the European Union, the Arab League or the United Nations could break the stalemate. The danger is that the stalemate - as bloody as it currently is - may yield to more violence.

Sanctions, or the threat of sanctions, would at least represent some movement on the part of the international community. The youth movement has been calling for more international involvement, which could involve travel restrictions on Saleh and/or his inner circle and the freezing of assets, such as were used against Libya's Qaddafi.

There is also the novel experience of the Arab League, who last week used the serious diplomatic weight of suspending Syria to try to push Al Assad to end the violence against his people. This week in Yemen's capital, a rally was held to call on the Arab League to suspend Yemen's membership. Just a week ago that would have seemed an unimaginable situation. Now, the use of such a suspension - only once previously invoked when Egypt was suspended following the Camp David accords - has become possible, even plausible.

And then there is the carrot of safe haven in another Arab country - although, given that Saleh seems uninterested in the GCC-brokered plan that offers immunity from prosecution, it may not be persuasive.

Some movement by the international community is essential because it might finally push Saudi Arabia and the United States - the two most powerful influences on Yemen's government, both of whom appear to have accepted that Saleh is the only game in town - into more coherent action.

The trouble with all of these options is that they might cause more of the very things they seek to end. None of the mooted suggestions will necessarily mean that Saleh leaves immediately - the most pressing issue is to stop the bloodshed of civilians and to make Saleh take the GCC plan seriously.

Yet Saleh and his supporters have shown their determination to stay in power. At the same time, the youth movement is unlikely to give up, having persevered peacefully for so long in the face of violence. Having seen other protest movements succeed in the Arab world, the movement is determined to continue.

In Sanaa's "Change Square", the spiritual heart of an uprising that has spread to other cities, as many as 150,000 people can be found camping out, living in the square - really a series of connected avenues, so wide have the protests grown.

The protesters, despite incredible odds, remain connected to the outside world via blogs, email and social-networking sites, and good humoured, poking fun at their situation and that of Yemen's political order.

The protest movement is frustrated by the GCC deal, seeing it as offering Saleh too much. "No immunity" is a call often heard. That the main deal on the table is unacceptable to most of the protesters is serious, a harbinger of more conflict. It is noteworthy that the action that has thus far proved most likely to remove Saleh from power was a bomb attack on his compound that forced him to seek medical treatment abroad.

The fear in Yemen, the fear in the Middle East, is that attempting to cut the Gordian knot of Yemen's uprising might only break the already weak chains that still slimly hold the country together.

Faisal Al Yafai is a columnist at The National. Follow him on Twitter: @FaisalAlYafai

International censure may be link to begin domino chain in Yemen

Of the three Arab leaders that have resisted the winds of Arab change these past few months, Yemen's leadership remains the only one to escape serious international censure.

More from The National