It rarely gets too hectic on the sleepy coastal road running out of Fujairah, but as the sun crests the Hajar Mountains and workers in the industries of Al Bidaya down tools in readiness to break the fast, a very audible silence descends.

The silence in the courtyard of the Al Bidya Mosque, the oldest in the UAE, is only broken by Imam Hafiz Ahmed washing his feet in preparation for Maghreb prayers in one of the last few days of Ramadan. Shiny-eyed and seemingly undeterred by the day's long fast, the Bangladesh-born imam greets us at the door of his black stone house just outside the mosque.

His doorbell is a melodious trill of chirps that harmonise with the sound of birds in his well-tended garden of cacti and sidr trees. "Whenever I read the Qu'ran here it gives me some inner satisfaction and, I hope, when people come here they feel that peace," he says through a translator.

Imam Hafiz has been at the helm of this mosque for six years. "I took first prize in a Holy Qu'ran Competition in Saudi Arabia in 1988, for reciting the entire Qu'ran by heart," he says. Before coming to the UAE 23 years ago, he was the personal imam for Moudud Ahmed, the once prime minister and then vice- president of Bangladesh during the military rule of General Hussain Muhammad Ershad.

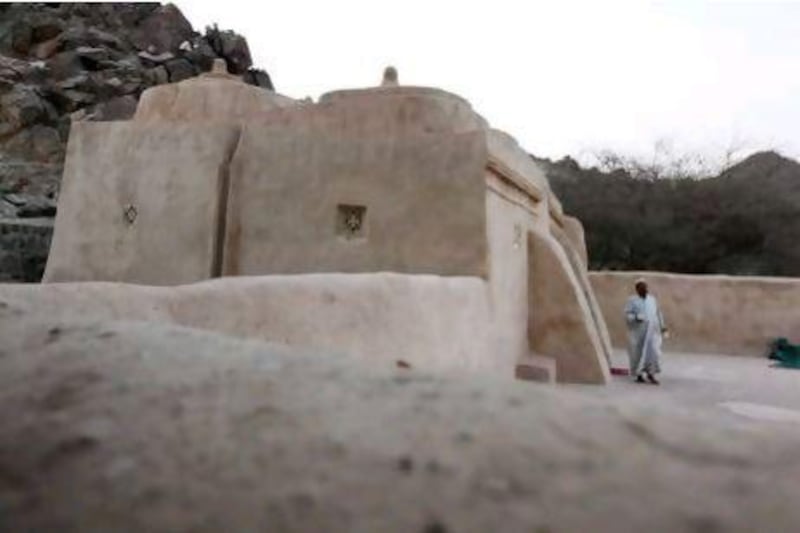

The building's patchy history, however, extends over half a millenia. The architecture is evidence of both its age and its eccentricity of design: it's a squat construction of mud brick and stone and is coated in a layer of pocked plaster. It has four shallow domes on the roof that each rise to a cylindrical nib and there are no minarets.

Situated at the foot of two rocky hills, each topped with Portuguese forts built in the 1800s, the mosque has an almost cave-like appearance that could blend into its surroundings were it not for its peach-like colour.

Carbon-dating carried out by an Australian team more than a decade ago gave the date of construction to be 1446. But who built it and details about the small community who lived around it at the time remains largely unknown, aside from clues found in the ruins.

It's clear that Imam Hafiz likes this patina of mystery about the place. He leads us through the arched door and into the cool, low interior of the mosque. Rows of peel-top pots of water glow from a small fridge in the corner, and overhanging fluorescent lights hum above us.

The imam points to the central column - an unusual feature in a space of this size. "When you touch the building, you feel something," he says, gesturing to the tactile plaster coating. "Looking up as well has some effect." The twilight outlines the strange reliefs that are dotted across the ceiling of the mosque, and in keeping with the idiosyncratic building, there is no particular regularity to these bars of wavy plaster. The shelves are moulded into the walls, and the minbar, the four short steps that the imam stands on to deliver each sermon, is sculpted into the structure. Save for the twilight glow of the mod-cons and a spruce-up in the past 10 years, this place has changed little since it was built.

Iftars do not take place in Al Bidya Mosque these days, but the imam still welcomes people to break their fast in the courtyard. It has a following of regulars throughout Ramadan, particularly among the nearby town's Bangladeshi workers. Standing outside the mosque is a family waiting to speak to the imam. They tell us that the age and the subdued cold of the building makes it a welcome respite from the heat, especially during Ramadan.

Just down the road in the small town of Al Bidaya, the courtyards of every mosque are lined with polythene sheets on which scores of men wait in silence to be served lamb mandi. It's a humid night, and a group we sit with tells us that they make a point of visiting the ancient mosque and its imam at least once a week.

It seems that many make the walk to Al Bidya Mosque specifically because it abides. The Adhan might be beamed in via a worn-looking satellite, but the building exudes a sense that the sun has set on many Ramadans here.

"My job is to to urge people to take the right path," says Imam Hafiz. "But every Ramadan we teach the same thing: that it is a period of personal prosperity."

Follow

Arts & Life on Twitter

to keep up with all the latest news and events

[ @LifeNationalUAE ]