The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo trilogy of books and films are a phenomenon in Europe, though their author, Stieg Larsson, didn't live to see his success. David Gritten goes to Stockholm to discover the story behind the stories, answer the questions surrounding the author's untimely death and meet the actress who plays the Girl. It's one of the most intriguing literary stories in living memory: an obscure 50-year-old author, who had never previously written fiction, produces a trilogy of thrillers. But before they reach the bookshops, he dies of a heart attack - and then becomes a posthumous publishing sensation.

This, in a nutshell, is the story of Sweden's Stieg Larsson, whose Millennium Trilogy, comprising The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo, The Girl Who Played With Fire and The Girl Who Kicked The Hornet's Nest, has now sold 27 million copies worldwide - a figure that is rising fast. All three books have been adapted for film, and between them have accounted for half the box office takings in Swedish cinemas this past year. The film of the first book has already been a major hit across Europe, and Hollywood will remake an English-language version of it, directed by Steven Zaillian, the garlanded screenwriter of Schindler's List.

This is remarkable enough, but ever since Larsson's untimely death in 2004 - a few months before the publication of The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo - burning questions about him and his authorship of the books have raged incessantly: who should inherit his fortune? Did he really write the books? Was his death really due to natural causes? The debates never seem to cease. Beyond argument is the fact that Larsson's crime thrillers have captured the imagination of the world's readers. This is largely because he created two memorable characters who join forces to become a chalk-and-cheese detective team.

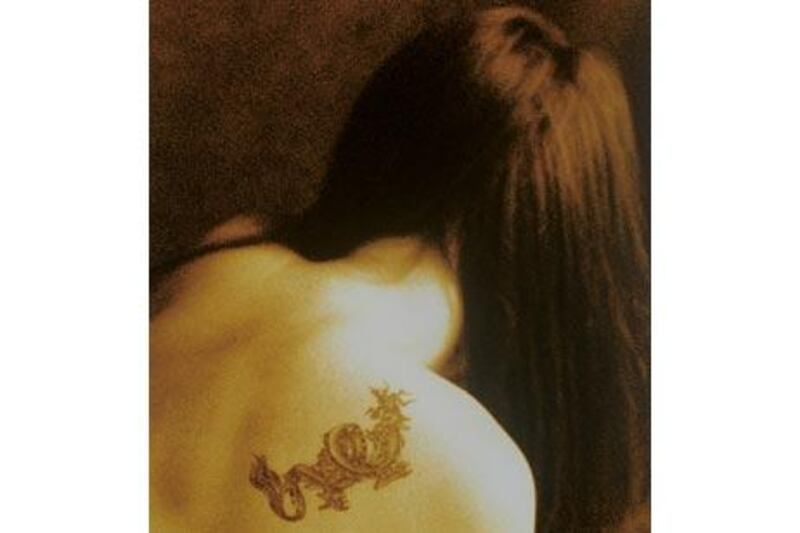

There's Mikael Blomqvist, a radical investigative reporter who assiduously tracks down greed and corruption in Swedish society. And above all, there's Lisbeth Salander - the Girl of the three titles - a rail-thin, bisexual, punkish 24-year-old with tattoos and piercings. She is socially dysfunctional and apparently incapable of expressing emotion; but she has a photographic memory, the ability to hack into any computer and a razor-sharp brain capable of extraordinary leaps of the imagination. Lisbeth is a remarkable, unforgettable creation.

Larsson told friends that he regarded Lisbeth as an adult version of the rebellious Pippi Longstocking, the heroine of Sweden's best-known children's books. It's no accident that a young detective in these books is named Calle Blomqvist, the name of another of Astrid Lindgren's fictional detectives. Michael Nyqvist and Noomi Rapace, the actors who play Blomqvist and Lisbeth, have become household names. Before taking the role of Lisbeth, 31-year-old Rapace was moderately well-known for her work on stage and in art-house films. Now the Swedes regard her as a superstar.

I decided to visit the epicentre of the Stieg Larsson imbroglio: Sweden's capital, Stockholm. It is a handsome city with imposing architecture, and is built on water - a collection of islands linked by bridges. It has an orderly, sedate air. The 7cm of snow on the ground that greeted my arrival made it feel even calmer than usual. Yet the snow had not muffled the controversy. The receptionist in my hotel rolled his eyes when I told him why I was in town. "Stieg Larsson?" he said. "In Stockholm, it seems this is all anyone talks about."

So it would seem. Reportedly there are several biographies of Larsson in the offing, written by friends. His story has been a tourist magnet for three years now, in a manner that confirms an official seal of approval. The Stockholm City Museum, housed in a 17th-century palace, offers guided tours that shed light on Larsson and his works. These "Millennium Tours" promise, according to the museum's pamphlets: "a city walk in Mikael Blomqvist and Lisbeth Salander's footsteps".

They have been remarkably successful. The City Museum's Sara Claesson said that 5,000 visitors took the guided tour last year, and a similar number did so on their own, using the museum's map for guidance. "Last month, a party of 20 took the tour in temperatures of minus 10 degrees," she added. The museum provided me with my own tour guide - Lena Erlandsson, a cheerful, knowledgeable woman who set off briskly up steep, narrow cobbled streets, all the harder to climb in the snow.

The landmarks on the tour are especially familiar to those who know Larsson's first novel, The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo. In it, Mikael Blomqvist, having humiliatingly lost an expensive libel suit brought against him by a wealthy financier, decides to lie low for a while, and take a leave of absence from Millennium, the radical magazine he co-founded. But he takes on another challenge: to investigate the 40-year-old case of a missing, probably murdered, teenage girl born into a powerful Swedish industrial dynasty.

In the course of his investigations, Blomqvist meets Salander, who is working as a researcher for a security company. They pool their resources to solve the case. Yet Larsson's story is more than a mere detective thriller. He clearly had an agenda, part of which was to highlight violence against women in his country. The original Swedish title of The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo, both the book and the film adapted from it, was Men Who Hate Women. And Lena Erlandsson points out it was Larsson's original plan to write 10 novels featuring Blomqvist and Salander, with Men Who Hate Women as the overall title.

The novel's four main sections each carry a chilling statistic on this subject. For example, 18 per cent of the women in Sweden have, at one time, been threatened by a man. Or 46 per cent of the women in Sweden have been subjected to violence by a man. Larsson also wanted to highlight the influence of far-right political groups in Sweden. The country was neutral in the Second World War, but many Swedes were sympathetic to the aims of the Nazis, a fact that Larsson felt had never been truly acknowledged in Swedish society.

He became an expert on far-right and fascist groups in Sweden and founded the Expo Foundation, whose magazine is the inspiration for Millennium in the novels. In The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo, Blomqvist and Salander unearth disturbing facts about members of the wealthy family they are investigating, including past Nazi links. The Millennium Tour incorporates all these preoccupations, and throws fresh light on the way Stockholm is portrayed in the books.

The tour starts and ends on Sodermalm, a large island to the south of the city, where both Blomqvist and Salander separately live. This, says Erlandsson, is significant: "Sodermalm", or "Soder", the south, has always been the radical, bohemian part of the city. It was the working-class area, and although it has now been gentrified, it is still very different from other parts, which one might associate with the state, the courts, or the wealthy.

"Stieg Larsson shows his attitude towards various characters based on where they live, and for him, the good guys live in the south of the city. It's something of a nod and a wink to the people of Stockholm about where his sympathies lie." Tourists get to visit Blomqvist and Salander's favourite "Soder" haunts. One is his attic apartment high up on the corner of a hilly street called Bellmansgatan. (In the books, the entrance is at street level, but the real building's entrance is from a walkway above the street.) Another is Tabbouli, the inspiration for Samir's, a Lebanese restaurant on Tavasgatan, where Mikael and his radical friends hang out.

On the fashionable street Gotgatan, Millennium's editorial office is located above that of Greenpeace. (In the film, the building used is a few doors down.) The Lunda Bridge is significant in the books because it was the fastest way between Blomqvist and Salander's apartments. Then there's the Mellqvist coffee bar on Hornsgatan street - Blomqvist's favourite hangout, and a place Larsson not only frequented but where he often sat and wrote. The synagogue on St Paulsgatan is where Salander's employer, Dragan Armanskij, meets Detective Inspector Jan Bublanski, a member of its congregation. Strikingly, nothing about the building advertises it as a synagogue. Erlandsson tells me it has been the target of far-right groups in the past.

"Stieg Larsson was thorough with details," she added. "He names all the streets and all the street numbers where people lived, but not Lisbeth Salander's place on Lundagatan - maybe because of all the dramatic, traumatic stuff that happens to her in there. So the tour doesn't go over to that street." Since Lisbeth Salander does not actually exist, I decided to talk to Noomi Rapace, who plays her in the three films.

We meet in a setting from which Salander might recoil: for lunch at the chic, expensive Lydmar Hotel, set on the sea front. Oozing opulence, it's no place for a young punk with an attitude. But Rapace looks anything but punk. Elegant and slim with her dark hair in a gamine cut, she attracts the gaze of every diner in the room as we progress to our table. She carries her new-found celebrity well. You wouldn't take her for Swedish, with her dark hair and eyes and prominent cheekbones. And that's before she starts to talk about Salander, about Larsson and his writing. Not for her are the polite pleasantries of Swedish discourse; it turns out she has quite an attitude herself.

"I think Stieg Larsson was pretty brave," she says. "He wanted to bring up things that we don't like to talk about, or like to ignore. In Sweden everybody has this perfect surface. Everyone's very polite and controls their feelings. "For instance, there's certainly violence against women here, but it gets swept under the carpet. We have immigrants, but you don't see them in the centre of Stockholm - a lot of people here don't feel part of this society. And we still have old Nazis, Swedes who agreed with Hitler. We've never addressed this.

"Stieg was working against all those things and he wanted to force people to see those problems. The most depressing thing is, we're afraid of talking about them." Rapace's father was a Spanish flamenco singer, and she spent years growing up in Iceland. Her adolescence was comparable to Salander's: "When I was 14, I had piercings, I dyed my hair blonde, I looked terrible." She left home at 15, enrolled in a theatre art school, and became self-sufficient. Now she is married to an actor and has a six-year-old son.

Rapace insists she will not play Salander in the Hollywood remake: "It would be cynical of me." And she refuses to be drawn into speculation about Larsson's death or gossip about his legacy. "All these rumours," she says disgustedly. "Stieg was a hard-working man. I met a friend of his who said he smoked a lot and worked like a madman. I don't think he lived such a healthy life." She wrinkles her nose: "Conspiracy theories!"

She has a point. Almost every day the Swedish press unearths some new controversy regarding Larsson, which the outside world digests with growing interest. There are rumblings (some promoted by "friends" with Larsson biographies to peddle) about whether he had the talent to write these books himself. Then there's the feud between members of his family and Eva Gabrielsson, his partner for more than three decades. (They never married, and he never made a will.) At stake are the proceeds of his estate, last valued at Dh116 million, but rapidly rising daily with every book sold.

Finally, there's the delicate question of the circumstances of Larsson's death. Coronary thrombosis was the official verdict, but that has not prevented the airing of some outlandish theories. Larsson certainly had enemies among Sweden's far-right political groupings. Christopher Hitchens, writing excitably in Vanity Fair, noted that he died on the anniversary of Kristallnacht, a key date in Nazi history: "Is it plausible that Sweden's most public anti-Nazi just chanced to expire from natural causes on such a date?"

Noomi Rapace simply shakes her head in disbelief at such theories. Lena Erlandsson shrugs dismissively, adding: "I think he was absolutely the man who wrote the books." Still, the media keep gossiping and the controversy around Larsson continues to swirl. And, given the unlikely nature of even the verifiable stories about the life and death of this extraordinary man, is it any surprise? To find out more about adapting books for films, join Vikas Swarup, author of Q&A, the book that inspired Slumdog Millionaire, crime writers Mark Billingham and Jeffrey Deaver and the acclaimed author Chris Cleave for a panel discussion entitled 'From Page to Screen: Secrets of Successful Adaptation' on March 13, 5.30pm at the Emirates Airline Literature Festival, InterContinental Hotel Event Centre, Dubai Festival City.