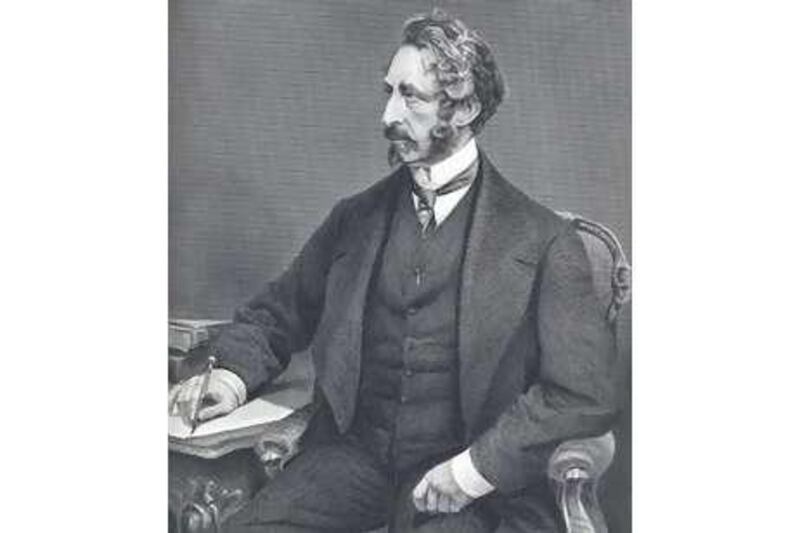

"It was a dark and stormy night; the rain fell in torrents - except at occasional intervals, when it was checked by a violent gust of wind which swept up the streets (for it is in London that our scene lies), rattling along the housetops, and fiercely agitating the scanty flame of the lamps that struggled against the darkness." It might not look like much, but without the opening segment of the above sentence - written by the Victorian novelist Edward Bulwer-Lytton in 1830 - the annual bad fiction writing competition (official title: the Bulwer-Lytton Fiction Contest) might never have seen the light of day.

The tongue-in-cheek contest, which was dreamt up by the English department of San Jose State University in California, celebrates the worst examples of purple prose - a literary criticism used to describe passages or sometimes entire literary works that are overly extravagant and flowery in their nature. The contest began in 1982, under the captaincy of Professor Scott Rice, and was named in honour of Lytton thanks to the long-lasting legacy of his much-quoted opening sentence, from the novel Paul Clifford. The book, which was described as a Gothic-horror, has become a textbook example of purple prose given its overly Romantic themes.

Additionally, "It was a dark and stormy night" has since been parodied by a number of authors. Most famously Charles Schulz, the creator of the 1950s comic strip Peanuts, used the line several times with regards to the character of Snoopy - who was constantly seen to have written the phrase as the opening line to his unfinished novel. Other writers to make use of the phrase include the sci-fi novelists Terry Pratchett and Neil Gaiman, in their 1990 hit novel Good Omens, and Phillip Pullman with Spring-Heeled Jack (1989).

The rules of the competition, in which entrants are invited "to compose the opening sentence to the worst of all possible novels", state that each entry must consist of only one sentence. Furthermore, while there is no word limit, the contest organisers do not recommend anything above 60 words, and all entries must also be original works that have never been published. More that 10,000 people have taken part in the annual competition since it began - not bad when you consider that only three people entered the event back in 1982.

This year's awards saw Molly Ringle, from Seattle, named as the grand prize winner last month for her ludicrous opening sentence - which compared a long-awaited kiss to a gerbil drinking from a water bottle. Other winners included Steve Lynch, in the Detective category, for: "She walked into my office wearing a body that would make a man write bad checks, but in this paperless age you would first have to obtain her ABA Routing Transit Number and Account Number and then disable your own Overdraft Protection in order to do so". Rick Cheeseman was also a winner with his fantasy-themed opener: "The wood nymph fairies blissfully pranced in the morning light past the glistening dewdrops on the meadow thistles by the Old Mill, ignorant of the daily slaughter that occurred just behind its lichen-encrusted walls, twin 20-ton mill stones savagely ripping apart the husks of wheat seed, gleefully smearing the starchy entrails across their dour granite faces in unspeakable botanical horror and carnage - but that's not our story; ours is about fairies!"

Of course, while the opening line is important, we suggest that the Bulwer-Lytton Fiction Contest is missing out on a whole world of overwrought literature by thus limiting their contest. After all, some of the world's biggest sellers in the book charts offer whole tomes full of misplaced adjectives, malapropisms and ill-conceived plot devices. A master at the art of over-description is Dan Brown, the author of The Da Vinci Code and its sequels.

Take this description of air quality, in The Da Vinci Code: "he could taste the familiar tang of museum air - an arid, deionized essence that carried a faint hint of carbon - the product of industrial, coal-filter dehumidifiers that ran around the clock to counteract the corrosive carbon dioxide exhaled by visitors." Are those coal-filter dehumidifiers really essential to the story? We don't know, but his words trip off the tongue like a hopscotch-playing schoolgirl whose criss-cross-laced woven polyester shoelaces have been secretly tied together in a double slip knot. Hang on - is purple prose contagious?