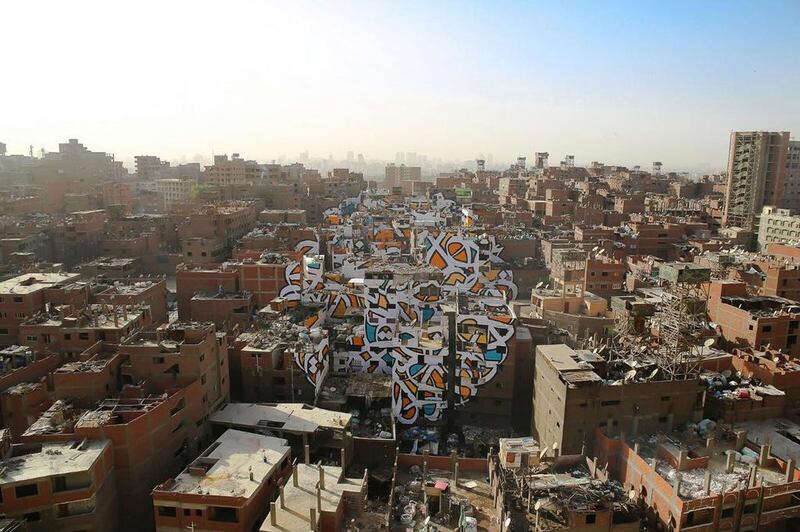

At the beginning of December, the French-Tunisian artist eL Seed added a form of postscript to his most ambitious project to date, the Cairo-based installation Perception, a circular knot of Arabic script that sprawls across the facades of more than 50 buildings.

Completed last March, Perception is a mural that challenges the limits of legibility and, being anamorphic, can only be fully comprehended from a single vantage point in the Zaraeeb neighbourhood of Manshiyat Naser, a predominantly Coptic Christian eastern ward of Cairo that is popularly referred to as the capital's "Garbage City".

At eL Seed's request, some of the residents who had helped to create the mural were invited to the opening of Zaraeeb, an exhibition of his canvases that not only echoed Perception's colours and calligraphy, but also contained some of their names as a token of the artist's appreciation and thanks.

The exhibition was held at ArtTalks Egypt, a gallery in the upmarket suburb of Zamalek on Gezira Island, a cosmopolitan neighbourhood in central Cairo that borders the Nile. A place of embassies, luxury hotels, antique shops and chic cafes, Zamalek could not be more different from Manshiyat Naser, a place that, in the popular Cairene imagination, is defined by mountains of rubbish, slums and dirt.

eL Seed with children from the Cairene suburb of Manshiyat Naser at the opening of Zaraeeb at the Art|Talks Egypt gallery in December 2016. Courtesy Mahmoud Shakweer

"I always make sure that I am writing messages, but there are also layers of political and social context and that's what I am trying to add into my work," eL Seed tells The National. "The aesthetic is really important, that's what captures your attention, but then I try to open a dialogue that's based on the location and my choice of text."

In the case of Perception that text is a quote from the 3rd century patriarch of Alexandria, St Athanasius: "Anyone who wants to look at the sunlight clearly must wipe his eyes first."

The Zaraeeb residents' cross-town excursion not only epitomised the spirit of Perception, a work predicated on a unique combination of Arabic calligraphy and a sense of place, but also echoed the trajectory of eL Seed's career, a journey that started with tagging and graffiti in the western suburbs of his native Paris but now involves the creation of large-scale public artworks in North Africa, Brazil and most recently Dubai, the city he has called home since 2013.

“Everything started for me as a quest for identity. I was born and raised in France as a child of Tunisian parents, but by the time I was a teenager I had reached a point where I thought that I needed to choose between my French and my Arabic identity,” he says. “I felt that I couldn’t connect both of them together.”

That sense of dislocation encouraged eL Seed to investigate his Arabic roots and, at the age of 18, he began to learn to read and write the language.

“It was important for my parents that we stayed close to our Arabic roots – we used to go to Tunisia every summer – but I couldn’t claim myself as a 100 per cent Tunisian because I couldn’t read or write Arabic,” the 35-year-old explains.

“That is how I discovered calligraphy. The first time I saw somebody doing it in front of me I found it so beautiful that this dynamic work of art could be made in just a few seconds, and that what’s attracted me most at the beginning.”

Starting on paper, eL Seed began by reproducing examples of classical calligraphy but soon graduated to working on walls which is where he developed his now signature style without, as he says, “knowing the rules or techniques”.

“When I look at traditional Arabic calligraphy from where I’m standing today, I’m just continuing what has been done before,” he says.

“I was inspired by the people who came before me, and my story, my identity and my experiences made me do what I do today. I’m just playing with letters, like [they did] in hurufiyya.”

The hurufiyya, or hurufism, eL Seed refers to is a movement in modern abstract Arabic and Iranian art that takes calligraphy, words and letter forms as its point of departure but which declines to offer any guarantee of legibility or linguistic meaning.

"Indeed, the hurufist would start with these letters in the very hope that there will be no return to them," explains the Lebanese academic Charbel Dagher in Arabic Hurufiyya: Art and Identity, a survey of the phenomenon which, as a result of the support of the Sharjah-based Barjeel Art Foundation, has just been translated into English for the first time.

Without You or Me or The Nostalgic Hallucination by Rachid Koraichi. Courtesy Barjeel Art Foundation

Thanks to Dagher's exhaustive research, Arabic Hurufiyya took most of the 1980s to complete but when it was finally published in Arabic in 1990, the book marked the first detailed attempt to chart the variety of approaches to the use of letters, words and script in the work of modern Arab artists such as Shakir Hassan Al Said, Yousef Ahmad, Dia Azzawi, Rachid Koraïchi and others.

A body of work that is uniquely of its region, the hurufism identified by Dagher shuttles between modernity and tradition, drawing on the sacred role that words and text have played in Islam and the Quran, while exploring the limits of legibility and abstraction, resulting in works that variously reflect on history, identity, politics and faith while remaining resolutely modern.

“It is interesting to note that modern Arabic poetry and hurufiyya began roughly around the same time. Is it merely coincidence that these two movements were born in the same period – and perhaps even in the same year?” the academic wrote in his original introduction.

“Can the origins of the Arab liberation and independence movements be compared to those of these two art currents? What dialectics did hurufiyya establish between art and identity?”

There have been a number of exhibitions about hurufiyya in the quarter-century since Dagher’s text first appeared that have attempted to investigate similar questions, two of which have been mounted by the Barjeel Art Foundation.

In 2014, Mandy Merzaban curated Tariqah at the Marayah Art Centre in Sharjah, which was accompanied by a catalogue that contained extensive essays by Dagher and the Palestinian artist Kamal Boullata, while in November, Hurufiyya: Art & Identity opened at the Bibliothecha Alexandrina in Egypt to mark the publication of Dagher's seminal text in English.

Rafa Al Nasiri’s Image (Amman). Courtesy Barjeel Art Foundation

Curated by the Barjeel Art Foundation's Karim Sultan, the show features work from the Foundation's collection, such as Rafa Al Nasiri's Image (Amman) (1988) and Rachid Koraichi's Without You or Me or the Nostalgic Hallucination (1986).

“One of our objectives is to investigate, develop and exhibit various aspects of regional art history,” Sultan said at the exhibition opening. “And hurufiyya is an important 20th century movement that lies between the international modern art of the day and concerns of artists in the Arab world. It is a fascinating entry point to exploring works and styles from the 20th century to our present moment.”

As a historical document, Dagher's survey ends in the late 1980s, but the role of hurufiyya in the present moment has been documented by a second text, the lavishly-illustrated Signs of Our Times: from Calligraphy to Calligraffiti, which was published by Merrell in September.

A self-described visual essay on the subject, Signs of Our Times has been written by the independent, London-based curator Rose Issa with contributions from Juliet Cestar, Venetia Porter and a foreword by the artistic director of London's Serpentine Galleries, Hans Ulrich Obrist.

Issa and Porter have been working together since the mid-1980s when Issa, a Lebanese-Iranian emigre who made London her home, first began to encourage Porter, now the British Museum’s assistant keeper of the Islamic and contemporary Middle East, to collect modern and contemporary work from the region.

Porter went on to curate the influential 2006 travelling exhibition Word into Art: Artists of the Modern Middle East, while Issa has not only served as an advisor on Arab art to the Smithsonian Institution, the Jordan National Gallery and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, but also organized the first Arab Film Festival at London's National Film Theatre in 1987 and the first exhibition of contemporary Iranian art at the Barbican in 2001.

Inspired by the approach used by Obrist in his Conversation Series, the format of Signs of Our Times consists of individual, illustrated entries for each artist and their responses to the same three questions: "How did you come to art, or how did art come to you?", "How did writing/calligraphy/words come into your work, or how did you come to words, writing or the morphology of letters in your work?" and is there "Anything you may want to add in terms of sources of inspiration, whether poetry, historical events or aesthetics?"

The book starts, like Dagher’s with the Aleppo-born, Iraqi artist Madiha Omar’s groundbreaking hurufist works that were exhibited in Washington DC in the 1940s, and comes up-to-date with the work of contemporary artists such as the Iranian calligrapher Golnaz Fathi and the Bethlehem-born Emily Jacir, as well as the Kuwait-based Farah Behbehani and eL Seed.

El Seed, Onk el Jmel, from the Lost Walls series in Tunisia. Courtesy eL Seed. From Arabic Hurufiyya: Art and Identity by Charbel Dagher (Skira, November 2016)

"It all started with the independence movements in the late 1940s and 1950s when artists had to show that they were also independent aesthetically," Issa tells The National.

“How could they compete in abstract or figurative terms with the West and with Europe with the artists in Paris and New York? They went to the roots of their culture,” she says.

“It wasn’t just a matter of finding a new aesthetic language and imposing that as an original source of inspiration, it was also about bringing a new aesthetic to the language of art,” says the curator. “But it’s not a trend that is limited in time. It started as a cry for independence and originality but it turned into a pleasure, of expressing identity not only of being original but also of who you are.”

Issa’s take on the trajectory of hurufism from the 1940s to the present day chimes with the personal and aesthetic journey travelled by eL Seed.

“Trying to understand Arabic calligraphy and to dig into this art made me read and made me learn more and more things about my history, about my people, about my culture,” says the artist.

“When I felt like I was fully Arab, when I could read, write and make art in Arabic, then I found that part of me was still French and I realised that both could totally work together.

“If I had just been born and raised in Tunisia, I would never have found this struggle of trying to decide which path to choose. Arabic calligraphy made me accept my French identity as well, and I was happy with that.”

• Art101: eL Seed, A Conversation with the Artist will take place at Alserkal Avenue's Nadi Al Quoz in Dubai at 6.30pm on Sunday, January 22. To reserve a seat, contact events@alserkalavenue.ae

• The Barjeel Art Foundation's Hurufiyya: Art & Identity runs at the Bibliothecha Alexandrina, Alexandria, Egypt, until January 28. For more details,visit www.bibalex.org

Nick Leech is a feature writer at The National.