Facing an uncertain future, the religious and ethnic minority groups across Iraq and Syria today have also served as a reminder of the region’s great diversity. The end of a year marking the centenary of the start of the First World War seems a propitious time to assess the relationship between nationalism, ethnic identity and religious affiliation that played out in Greater Syria and the toxic mix of colonial self-interest, authoritarianism and religion that still exacts its price today.

When the Ottoman Navy launched an attack on Russian naval bases in the Black Sea early in the First World War, the once mighty Ottoman Empire had been in decline for more than two centuries. The great powers of Europe had rolled back its frontiers and encircled it with their colonial possessions, but its main losses had been to the nationalism that spread among its subject peoples as the 19th century wore on. By 1914, it had lost its dominion over the Christian peoples of the Balkans, and its European territory was reduced to the area that Turkey retains today. Yet in Asia it still stretched through Greater Syria to the edge of the Sinai Peninsula, along the coast of the Red Sea to Yemen, and down the Euphrates to Basra. More than half its remaining territory was predominantly Arabic-speaking. Nationalism might have been the political idea of the day, but how far had it caught the imagination of the empire’s Arabs? Would the coming war bring them their moment of destiny?

The Ottoman Empire had always been a multi-ethnic state based on loyalty to the ruling dynasty, not on a shared national identity. The great marker of difference in the empire had been religion. Originally, Christians and Jews had had a subordinate status prescribed by Sharia, while Muslims who were not Sunnis had been regarded as the lowest of the low. Non-Muslims had had to pay extra taxes and recognise the superiority of Muslims. They had also been exempt from military service. Yet these distinctions had been swept away – at least in theory. In decrees passed in 1839 and 1856, discrimination based on religion was abolished and Ottoman liberals hoped that a new spirit of Ottoman patriotism would be engendered. These decrees can be regarded as an extension of the secularisation that took place in 19th-century Europe. In Britain, for instance, it was not until 1829 that full rights were granted to Roman Catholics.

Yet the adoption of European secular ideas was complicated for the Ottomans, since for them ethnic group and religious sect overlapped and were frequently identical. The Ottoman Greeks had always been recognised as a millet, a separate religious community to which the sultan allowed internal self-government. During the death throes of the empire after the First World War, an exchange of populations would take place between Turkey and Greece. All Muslims, even if Greek-speaking, would be deemed to be Turks, and forced to leave the Kingdom of the Hellenes for the new, ethnically Turkish republic that arose out of the ashes of the burnt-out empire. On the other hand, Turkish-speaking Christians in Anatolia who attended Greek Orthodox churches were automatically considered Greeks because of the place where they worshipped. They, too, had to leave their homes for another land.

These events continued an earlier pattern. As the Christians of the Balkans cast off the Ottoman yoke after many insurrections and wars, national churches were at the core of the identities of the new internationally recognised states that finally emerged in Greece in 1832, Serbia and Romania in 1878, and Bulgaria in 1908. Local Muslims were often branded as Turks, automatically turned into aliens in their own land. Now the new Turkish republic defined its citizens as Sunni Muslims. This, incidentally, reincarnated its substantial Kurdish minority as “mountain Turks” and swept their separate ethnic identity under an Anatolian carpet.

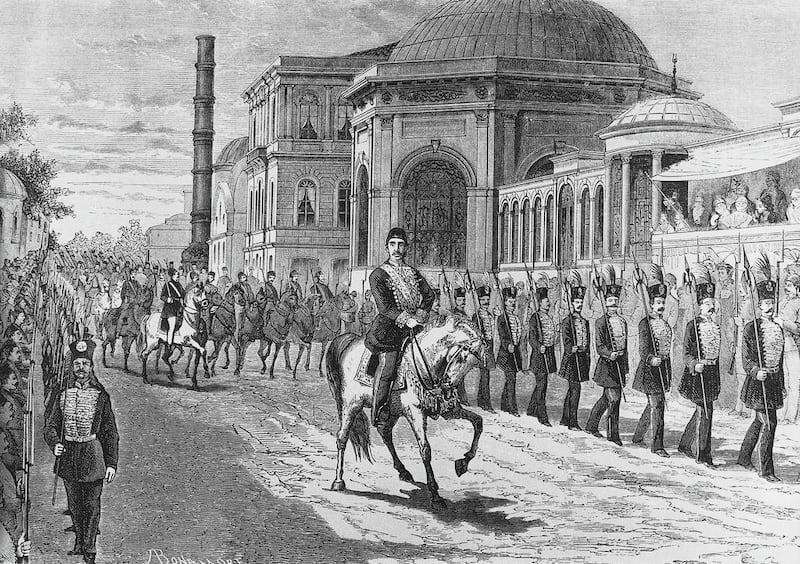

There was also another reason why the differences encapsulated by religion were slow to fade. The autocratically minded Sultan Abdul Hamid II, who ruled from 1876 to 1909, tried to give a new vigour to his religious title of caliph. This was an attempt to stem the tide of liberal reform in the empire, to rally its Sunni majority behind him and to give himself leadership over Muslims in other countries. This policy had a degree of success among Arabs and other non-Turkish-speaking Muslims throughout the Ottoman domains.

Although Arabic speakers made up nearly half the empire’s population in 1914, nationalism had not penetrated their hearts to anything like the extent that it had those of the peoples of the Balkans or the Armenians of eastern Anatolia. An important reason was that the Arabic speakers were far from homogeneous in terms of religion. Most were Sunnis, but many were not. In Greater Syria taken as a whole, 20 per cent or more of the population was Christian. There were important areas predominantly inhabited by groups who were not Sunni Muslim. Mount Lebanon was the domain of Maronite Christians and Druze, while the Hawran plateau was another Druze area and the mountains behind Lattakia were inhabited largely by Alawis, Orthodox Christians and Shiites. In the areas south of Baghdad down to the mouths of the Euphrates, the majority were overwhelmingly Shiites. Towns and villages predominantly inhabited by specific minorities could be found in many other places, and the largest Christian group – the Orthodox – were widely diffused but only rarely a clear majority in a particular district. There were large minorities in the cities. Aleppo was perhaps one-third Christian, while Baghdad was about 20 per cent Jewish. There were also many people in these provinces who spoke other languages. The largest group were the Kurds who were concentrated in particular areas of the north of what would become Iraq, but there were also Turkomans (tribes speaking a Turkic language) and Circassians (Muslims from the Caucasus, the Black Sea and Balkans who had been victims of so-called ethnic cleansing or fled to the sultan’s dominions rather than live under advancing Christian rule), as well as pockets of Armenians and Syriac-speaking Christians. The highest echelons of society in the cities were bilingual in Turkish and Arabic.

This religious diversity and the presence of other groups complicated ideas of nationalism in a way that had not applied in much of the Balkans. Like all ethnic groups, Arabic speakers were administratively invisible in the empire, since census returns only indicated religion. The word “Arab” had had pejorative connotations for hundreds of years. It was associated with wild and unruly Bedouin tribes who inhabited deserts and other inhospitable terrain and lived by brigandage. Any self-respecting Damascene, Baghdadi or Jerusalemite would identify himself by his extended family (lineage was always extremely important), his religion and his home city or province. Arabic had a respected place as the language of Islam and religious learning, and was used for these purposes by native Turkish speakers as well, but Turkish was the language of government and the army. An Arabic dialect might be the local vernacular, but that was not a matter of great significance.

Nevertheless, in the second half of the 19th century a new self-awareness began to flicker into life among Arabic speakers. It was connected with the gradual spread of literacy and (for Arabic) the still-new medium of print. While scholars began to print editions of the classics of Arabic literature for the first time, the language was revived to make it a form of communication for the ideas of the modern world. New disciplines like journalism and the writing of stage plays on the European model appeared, while the dissemination of ancient poetry, historical writing and religious texts instilled pride in the language’s heritage. This was shared by Arabic speakers of all persuasions, and many Christians as well as Muslims made a contribution to the scholarly process by writing Arabic dictionaries and encyclopedias, or editing the work of the poets and masters.

This renaissance of the language took place simultaneously in Greater Syria and Egypt. It was a cultural, rather than a political, event in both – but it had political consequences. In Egypt, Arabic displaced Turkish as the language of government and the governing elite (even though at the dawn of the 20th century, drill sergeants still barked orders to peasant conscripts in Turkish, a language neither they nor the recruits really understood). In Greater Syria, many people came to resent the fact that Turkish was the sole official language of the empire. They began to call for greater use of Arabic. While Abdul Hamid’s policy of portraying himself as caliph shored up support for him among some Arab Muslims, others began to query whether the caliph should be an Ottoman Turk rather than an Arab. After all, Arabic was the language of Islam and the claim of the House of Othman to religious leadership was far from self-evident.

After the Young Turk revolution in 1908, when a junta of army officers imbued with Turkish nationalism became the effective government of the empire, there were calls for autonomy for the Arabic-speaking provinces, or even the transformation of the empire into a dual monarchy on the Austro-Hungarian model. But care had to be exercised when discussing such matters. Calls for independence could only be uttered from the safety of exile, or discussed privately in secret societies, and too many Arabic speakers still felt bonds of loyalty to the Ottoman state for an independence movement to get off the ground. There were Syrian Muslims right at the top of its official hierarchy, while the head of the sultan-caliph’s secret police was a Maronite Christian (it made perfect sense to have a non-Muslim in charge of running agents who spied on the sultan-caliph’s family). The empire might be weak, but it was still the best hope against European encroachment. It thus retained the loyalty of many Arab Muslims. At the same time, some Christians appreciated how its attempts at centralisation had led to more stability in the decades following horrific sectarian massacres of Christians on Mount Lebanon and in Damascus in 1860. Some Christians even hailed Abdul Hamid, the sultan-caliph, as malikuna – “our king”.

As many Christians and Muslims shared in a new prosperity, they became less guarded in their approach to each other. Political developments would transform this emerging sense of pride and fellow-feeling into fully fledged nationalism. In the Arabic-speaking Ottoman provinces, it was the empire’s ill-starred decision to enter the war against Britain, France and Russia that gave Arab nationalism its chance. In June 1916, following an agreement with Britain, Sharif Hussein of Mecca raised the banner of revolt against the Ottomans and called for the establishment of an Arab kingdom comprising the Arab provinces of the empire. The war ended with an “Arab government” under the Emir Faisal, one of Hussein’s sons, tenuously in control of what is now Jordan and inland Syria, including Damascus, Aleppo, Homs and Hama. With the exception of the Maronites of Mount Lebanon and the small European Jewish colonies in Palestine, the overwhelming majority of the people of the area wanted an Arabic-speaking state from Sinai to the Turkish border and stretching as far east as the river Kabura and Al-Jawf, which is now in Saudi Arabia.

Faisal ruled his tentative kingdom from Damascus until French forces took over the entirety of the area that is now Syria and Lebanon in July 1920. The French conquest followed the Anglo-French partition of the Ottoman provinces into League of Nations Mandates. This artificial division gave Syria and Lebanon to France, while allotting Palestine, Jordan and Iraq to Britain. In time, the people of Palestine would pay a heavy price for the incorporation of Britain’s promise to facilitate the establishment of “a Jewish national home” on their land.

In the short term, the actions of France and Britain made the consolidation of Faisal’s kingdom impossible. Yet words from a speech he gave in Aleppo on November 11, 1918, still ring in our ears today, telling us how a happier history might have been possible: “The Arabs were Arabs before Moses, and Jesus and Mohammed … Anyone who sows discord between Muslim, Christian and Jew is not an Arab. I am an Arab before all else … The Arabs are diverse peoples living in different regions. The Aleppan is not the same as the Hijazi, nor is the Damascene the same as the Yemeni. That is why my father [the sharif of Mecca] has made the Arab lands each follow their own special laws that are in accordance with their own circumstances and people.”

Not only was Faisal’s brief regime passionately in favour of religious equality (he underlined the point by making donations to churches and synagogues in Damascus), but he respected the regional differences of the Arab world in a way that important later nationalists, such as President Nasser of Egypt and the Baathist leaders in Syria and Iraq, would not. Faisal even convened a parliament to bolster his legitimacy in the eyes of the French and British. It is true that he was not universally accepted by Syrians. Many considered him a foreigner, while some even disparaged him as a Bedouin. He lost support as he was forced to make unacceptable compromises that would have meant a French Mandate over a kingdom confined to inland Syria, while conceding direct French rule along the coast and British rule in Palestine, the southern portion of Greater Syria. He was accused of selling Syria as though it were a commodity. Locally elected popular committees grew increasingly angry. Nationalist sentiment was not the property of any one group of Syrians (or Arabs), and the elite could not control how that sentiment was expressed. This forced Faisal to withdraw the concessions he had made to the Allies.

Faisal’s acceptance of constitutional rule, his flexibility and the existence of these locally elected committees show that democracy – if given the chance – might have put down roots in Greater Syria after the First World War. The committees demonstrated that a sense of Greater Syrian identity did exist. Arab nationalism had arrived at street level – and its passionate call for the unity and independence of Greater Syria was ignored by the great powers.

The call for independence would be revived in 1925, when much of Syria rose against their baffled French masters. The revolt was not sparked by the speeches or political agitation of intellectuals, but by French foolishness in treating the illiterate Druze peasants of the Hawran with contempt, leading them to rebel over their grievances. When the Druze forced a French withdrawal, the uprising spread like wildfire. Muslim and Orthodox Christian villagers joined the revolt and then Hama and Damascus rose in solidarity. The French had sought to exploit the religious cleavages in Arab society through a policy of divide and rule in the hope of perpetuating their presence, but found that they had failed. Sunnis, Druze, Shiites and many Christians fought against them together and died side by side.

The historian Michael Provence has described the 1925 revolt as “the largest, longest and most destructive of the Arab Middle Eastern revolts” against the Mandates, and pointed out how it served as a template for others, such as that in Palestine in 1936. Yet France and Britain crushed these revolts by massively reinforcing their garrisons with other troops from their worldwide empires. The bars of the cages created by the Mandates did not bend. When independence eventually came, centralising nationalist rulers failed to build stable, modern states. They were unable to free their countries from foreign meddling or to achieve justice for the dispossessed Palestinians. Instead of evolving into democracies, countries such as Syria, Egypt and Iraq descended into the nightmare of dictatorship. Their leaders no longer sought to move the masses, but to control and pacify them.

Religion and its rhetoric had always had a powerful role in Arab nationalism. Nationalists adapted concepts from Islam such as “jihad” to refer to the struggle for independence, and described Arabs who died fighting Muslim Turks or infidel French, British or Israelis as shuhada, or “martyrs”, irrespective of their religion. The language of the Quran lies deep in the hearts of Arabs of all faiths. As the ideals of Arab nationalism were thwarted by foreign powers and simultaneously corrupted from within, religion became an ever-greater focus for identity. By preventing political dissent, the dictators left religious militancy as the default option for the many aggrieved among their citizens. Such militancy thrived on hate speech against non-Muslims and Shiites. With the appearance of ISIL, we can now see the shipwreck towards which the Arab world has been sailing for decades.

John McHugo has written A Concise History of the Arabs, which was shortlisted for the Salon Transmission Prize in 2014, and Syria: From the Great War to Civil War.