As a child, Abigail Reynolds was in awe of her local library. She saw it as a “magic space where you could commune with the dead”.

Years later, while studying literature at Oxford University, she would often stand beside the 18th-century Radcliffe Camera building, and breathe in the scent of the stacks – three storeys of them, containing millions of books – wafting through an air vent.

So when she was asked to come up with a proposal for a significant journey to inspire a new body of work, the British artist knew almost immediately it would centre on her love of books.

Reynolds, whose project won the annual BMW Art Journey prize in May last year, spent the next five months travelling, mostly by motorbike, to lost libraries along the ancient Silk Road trade routes, from China to Iran, Uzbekistan, Turkey, Egypt and Italy. Some of the 15 libraries she visited are now impossible to access. Others lay buried for centuries and were rediscovered and restored in recent history.

Her trip culminated in the unveiling of an installation called The Ruins of Time: Lost Libraries of the Silk Road, which was exhibited at the recently concluded Art Basel Hong Kong.

Made up of five pieces, its fragments of metal gate-like structures, shards of glass, mirrors and film footage symbolise her often frustrating journey and the obstacles she encountered.

“My light-bulb moment was hearing a short clip on the radio about the Villa of the Papyri in Herculaneum, which was buried by the eruption of Vesuvius in AD79,” she says. “It was found but is still lost because we cannot read [the papyri]. They were carbonised by ash and we have found the technology to read them but that needs money for research, which has not been forthcoming They have only excavated one room but lack the funding to keep it open.

“I had a feeling there would be these lost libraries up and down the silk road because books are a precious commodity. All I had to do was find them.”

Abigail Reynolds records her travels using 16mm film and a Bolex camera. Courtesy BMW AG

After six weeks researching her trip, she headed to Xian in China, to the Forest of Stone Steles. There, she saw the steles, engraved stone sculptures, which form one of the world’s earliest libraries. Now in the 11th-century Confucian temple, the 3,000 steles were lost for centuries.

“Stone books were set up along the road outside the city. They were Confucian texts carved in stone to stop people copying badly,” says Reynolds. “People would copy them by making a rubbing – so they were like an ancient photocopier.

“They were abandoned when the city shrank, damaged by earthquakes and cracked, but when the city expanded again, they were found overgrown in the wilderness.

“They are now raised on blocks in a temple in the city so you look up to them.”

The imposing stone tablets are represented by the two largest pieces in her installation, Stelae I and II. But those works, with their fragmented, asymmetrical shape, discordant patterns and steel bars, are also symbolic of the barriers that often blocked her way.

While the other pieces and screens showing video footage she recorded during her journey are viewed through their bars and glass inserts, they are obscured, distorted and obfuscated, a sense she emphasised by punching holes through the 16 millimeter Kodak film she used to record her passage from East to West – so at the heart of her journey is now a black hole.

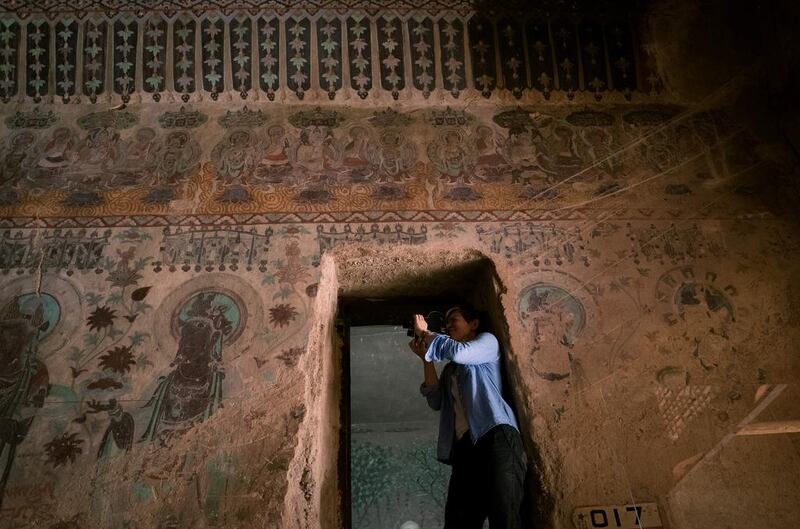

In Dunhuang, north-west China, she spent three days with her face pressed up against a metal door guarding a cave with a library inside, begging to be allowed in.

“I could not get permission to go in, but went every day just to get as close as I could – and then it was unlocked for me,” she says.

Inside, she found centuries-old religious texts reflecting an exchange of ideas and cultures. At every site, she would film, notate and absorb.

“I really tried to be present and think about what used to be there,” she says.

Some places required a stretch of imagination. The library in Xianyang Palace in Xian was destroyed in 206BC when the last Qin emperor Ziying was killed and the imperial home burnt down. In Egypt, too, Alexandria’s great library burnt down in AD392, but Reynolds followed the trail to Pergamon in Ephesus, Turkey.

“This Roman site had an enormous library,” she says. “When Alexandria’s library was destroyed, all the holdings from Pergamon were given by Marc Antony to restock the library, which burnt down again.

“Egyptians were worried Pergamon was rivalling their great library so they banned the export of papyrus, thinking that would stop them creating books – so they started using calfskin instead and called it pergamenos, which is where we get the word parchment.”

Destruction, past and present, was a common theme. Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan were off limits. So was Italy, where she tried and failed to get into the Herculaneum site.

“I am probably the only person who has been in all those places,” says Reynolds of the sites she did access, and she is writing a book about her experiences. “Just being there and being able to travel up and down like a book myself was incredible.”

Lost libraries visited

Abigail Reynolds’s

The Ruins of Time: Lost Libraries of the Silk Road

installation at the BMW Lounge at Art Basel in Hong Kong. Courtesy BMW AG

Stone Steles, Xian, China - found about 1080

Xianyang Palace, Xian - lost 206BC

Baisigou Pagoda, Yinchuan, China - lost 1970

Mogao Caves, Dunhuang, China - lost 11th century, found 1900

Palace Library, Khanate of Kokand, Uzbekistan - lost 1876

Nishapur, Iran - lost 1154

Hidden Libraries of Tehran - hidden 1979

Roman libraries of Turkey: Celsus in Ephesus (lost 262AD) Pergamon (lost 41BC), Nysa (lost 1402AD)

Library of the Serapeum in Alexandria, Egypt - lost 392AD

Cairo Genizeh, Egypt - found 1900

Institute of Egypt, Cairo - lost 2011

Bibliotheca Ulpia, Rome, Italy - lost around 600AD

Villa of the Papyri, Herculaneum, Italy - lost 79AD, discovered 1752

artslife@thenational.ae