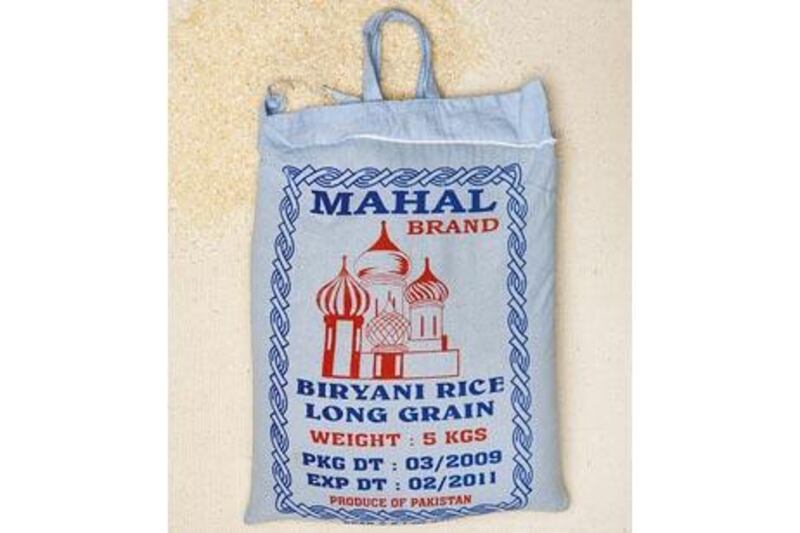

It feeds the world, provides a livelihood for 50 million Indian families, comes in an amazing variety of forms, is the ideal accompaniment for spicy food, and even the bags it is packed in are satisfyingly practical. Denise Roig rhapsodises about the humble staple, rice. A smiling Mogul emperor. A bucolic scene of distant mountains and placid lakes. A Bengal tiger. The Taj Mahal. Strolling down the rice aisle at LuLu or Carrefour you can catch a glimpse of images lovely enough to frame. That these sweet illustrations appear on packaging for that most prosaic of staples - rice - only adds to their charm. The cotton bags in which rice is sold here are made beautiful with these vibrant illustrations but they are immensely practical too - a perfect illustration of form and function.

They are made from closely woven cotton, with a zippered opening, which keeps out insects and dust. They are sturdily sewn with strong handles, making them easy to carry (you often see them used as shopping bags or slung over the saddle of a bicycle as an impromptu pannier). The bags can be stacked - whether in 2kg family size or 40kg restaurant size - making them easy to store in homes where storage is scarce. In a throwaway world, they are almost infinitely reusable and can be used to store not only rice but other dried grains, beans and pulses.

Rice is life in India, where 44 million hectares - the largest rice-growing region in the world - provide the main income for more than 50 million households. "India is the second largest producer of rice in the world," explains Narayan Raman, country manager for wholesale distribution and trading for EMKE Group, the Abu Dhabi corporation that owns LuLu Hypermarkets throughout the Gulf. "Last year we saw a record export of rice from India: two million tonnes."

One finds a record number of varieties in what Raman calls "our rice corner" at LuLu's Khalidiyah Mall branch: Egyptian rice, glutinous rice, jasmine rice, US-style par-boiled rice, samba rice, broken rice. Not all is from India: Pakistan, Thailand and Vietnam also export high-quality rice to the UAE, says Raman. But the reigning queen, rice buyers and cooks agree, is the creamy-white basmati. In Hindi, basmati means "the fragrant one", and this long-grain, non-sticky rice lives up to its name. Make a pot of basmati and your kitchen is infused with its sweet, rich smell. That scent, and its other winning points - when cooked, the grains nearly double in length, grow soft and fluffy, yet remain separate, perfect for mingling with spicy sauces - mean that basmati fetches 10 times the market price of other rice.

That nearly indescribable scent actually made headlines in September when a study from Cornell University in New York, dispelled long-held assumptions about the origins of basmati. There are basically two varietal groups of rice - Japonica and Indica - both originating in China some 8,000 years ago. For all this time, it's been assumed basmati was of the latter variety. But in isolating the gene that creates the scent, basmati has now been more closely identified with its Japonica cousins, such as sushi rice.

While India grows both Indica and Japonica rice, it's the north-western foothills of the Himalayas that offer the optimum conditions - soil, water, climate - for growing the very best basmati, says Raman. He's been buying rice for more than 25 years, travelling extensively to India, Pakistan and Thailand to individual rice-growing collectives. "I've learned over the past quarter century that the very best basmati rice is produced by the old, traditional brands from India, such as Lal Qilla." These are exported to the United States, Britain, Saudi Arabia and the rest of the Gulf. The low-grade rice, he says, stays in India for domestic consumption. In fact, for the past two years, Indian law has made it impossible to export anything but basmati. "This is a good thing for India, but not the best thing for stores like us, because, of course, it is more expensive."

But it is worth every dirham for chefs such as Rashid Raza, the head chef at Abu Dhabi's India Palace restaurant. "There are so many different types of rice," he says," but you're always using basmati rice in Indian cooking." The restaurant, which specialises in Mughal food, perhaps the richest and most lavish of Indian cuisines, buys its rice from a special grower in India. "It's got good flavour and good length."

In the restaurant's steamy kitchen, Raza is preparing to make chicken biryani. Lighting a burner, the flame shooting a foot in the air, he grabs a cast-iron pan, pours in a ladle of ghee mixed with crushed cashews, saffron, garam masala and rosewater, reducing it a bit before adding diced chicken, and finally, a small handful of chopped coriander and mint. And then, almost as an afterthought, a cup of cooked basmati, in saffron hues of orange, red and yellow. Flames rim and lap the pan as he lifts, shakes and clanks, making sure all the parts get their share of the searing heat. And there it is, a meal in less than six minutes.

The basmati may not have the starring role in a dish like this, but it is the foundation, the complement, that makes all the other parts work. For all its pedigree, its exotic origins, even its seductively beautiful presentation in the grocery store aisle, basmati rice begs to be cooked. I've never been that adept at cooking rice, scorching my share of pots, even succumbing to that easy fix: Minute Rice. But after talking to Narayan Raman, after watching chef Raza, I felt inspired to unzip my chartreuse-green bag of Lal Qilla, with its photo of pulao emblazoned in Fifties-bright colours and promises of "extra long", and make a pot myself.

I actually made two pots. So deliriously happy was I with the first that I immediately made a second. I loved both. Each grain was distinct, firm, fragrant and packed with nutty flavour. Now I understand why the Mogul emperor is smiling.

1. Measure 1 cup (200 g) of rice and place in a strainer or colander with very small holes. Rinse it under running water several times, since there is a great deal of starch clinging to the grains. Alternatively, rinse the rice in several changes of cold water, then soak the basmati in cold water for 45 minutes before cooking. This is a trick some Indian chefs claim makes the grains softer and less liable to break. 2. Drain the rice well, then place in a medium pot and add 1½ cups (375ml) of water. (The ratio for firmer rice is one cup rice to 1.3 cups water.) 3. Add a bit of oil, butter or ghee and a teaspoon of fresh lime juice. This will help keep the grains separate. 4. Cover the pot with a tight-fitting lid and bring to a boil. 5. Right after the rice begins to boil, lower the heat to medium-low and simmer for 12-14 minutes. Do not disturb the rice - don't even lift the lid to take a look - while it is cooking. 6. Remove the pot from the heat and let it stand, still covered, for another 5-10 minutes. The grains should be cooked and separate, and all the water will have disappeared. Fluff it with a spoon before serving.