Dr Donny George Youkhanna, former director general of the National Museum of Iraq, was the guardian of that country’s history and cultural patrimony – until he began getting death threats.

Forced to flee Iraq in 2006 after the United States-led invasion, he ended up in New York teaching at Stony Brook University.

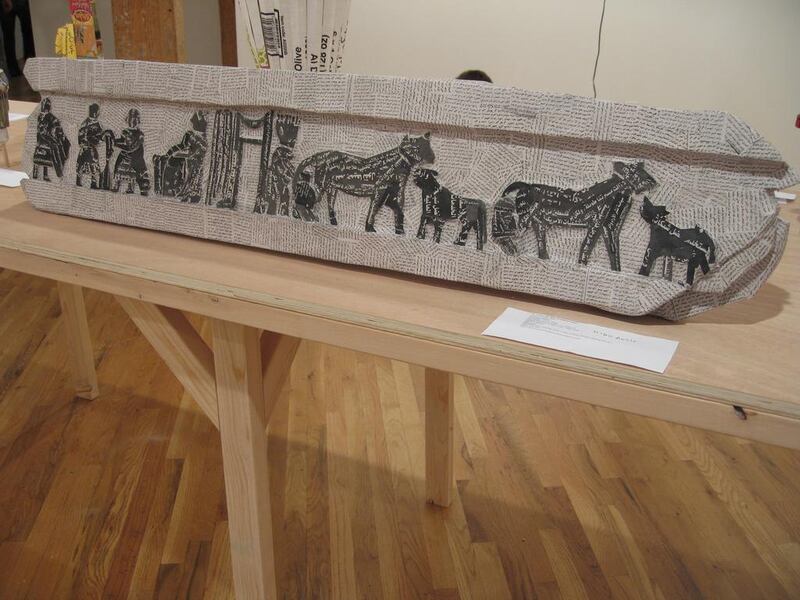

In 2007, he walked into the Lombard Freid Projects gallery space in New York to find it filled with familiar objects – life-size replicas of the artefacts looted from the museum in 2003, made not from stone but from the colourful packaging of Iraqi foodstuffs and scraps of Arabic newspaper.

Iraqi-American artist Michael Rakowitz was in Chicago when his gallery notified him that Dr George, as he was known, could be seen in the gallery every day. He had started giving impromptu tours of the artefacts, just as he had for the original works at the Museum in Baghdad.

“I was so moved,” Rakowitz says. “He and I spoke by phone and he told me how emotional he got because I had recreated these objects that are gone forever, and they were the exact size and had the right thickness, but they were made out of [different materials] that succeeded in making the ghost.

“He said that was as close as he was ever going to get to those objects again.”

The works that so captured the imagination of Dr George, who died of a heart attack in 2011, were part of a series Rakowitz has been working on for a decade. The Invisible Enemy Should Not Exist began in 2007, when Rakowitz pledged to recreate every artefact looted or destroyed during the invasion of Iraq.

In recent years, he has also added objects stolen or demolished by ISIL to his list. To date, he has recreated 700 objects from a list of 7,000, all using food wrappers and Arabic newspapers.

His sculptures lament the loss of Iraq’s cultural heritage but also speak for the loss of human life that accompanies acts of iconoclasm.

“There was a theory that I loved … that people would take these votive sculptures that one finds throughout Mesopotamia to the temples to pray,” he says.

“The votive sculpture was left behind as a surrogate for the person who was praying, while that person went back to their daily life. I liked the idea that these objects could become surrogates for the hundreds of thousands – millions – of Iraqis whose lives were completely destroyed, in one way or another, by the US-led invasion.”

One of Rakowitz’s sculptures was recently selected to top the Fourth Plinth in Trafalgar Square in 2018. Built in 1841, the plinth was intended to hold a sculpture of William IV but was left empty when the funds ran out.

Since 1999, it has been topped by a succession of works by contemporary artists. Rakowitz’s piece is a 14-foot-long reconstruction of the statue of a lamassu – a winged bull with a human head – that guarded the Nergal Gate in Nineveh, near Mosul, from 700BC until it was destroyed by ISIL in 2015. The colourful sculpture is made from empty cans of Iraqi date syrup.

“Using these temporary materials, like the detritus of Middle Eastern foodstuffs, has something to do with tracking the visibility of Middle Eastern culture in the United States, where my grandparents moved when they had to leave Baghdad in 1946,” he explains.

“I was enlisting these fragments of cultural visibility in the United States to remake these things that are now, for all intents and purposes, invisible.”

The sculpture shows the front of the lamassu, as well as the flat back, where it would have been attached to the gate it was supposed to guard.

The original artefact was reduced to rubble by ISIL, but Rakowitz consulted with archaeologists who told him there was Cuneiform writing on the back of the statue.

The words recreated on the sculpture resonate profoundly at a time in which the number of refugees globally is the highest ever recorded, and attitudes to migration are dividing societies around the world. “The translation is ‘Sennacherib, king of Assyria, king of the world, had the inner and outer walls built anew and raised them as high as mountains,’” says Rakowitz.

“So we’re talking about walls, we’re talking about power and something that comes from these ancient kingdoms, to warn us from the past.”

Rakowitz views his sculptures as “phantoms” – not replacements for, but ghosts of the lost artefacts.

He hopes his lamassu will serve a similar symbolic role as the almost 3,000-year-old artefact ISIL destroyed.

“It’s going to be positioned south-east, looking back towards Nineveh,” he says.

“My hope is that after the two years it’s on show in Trafalgar Square, I can gift it to Iraq, so that it can replace what was lost and it can still be a guardian of the past, the present and the future of Iraq’s memories.”

artslife@thenational.ae