For most of us, drawing anything other than the occasional distracted doodle is a lost skill. A UK campaign currently celebrating its 10th year aims to change that by reintroducing people of all ages and abilities to the pleasures and benefits of the art form. Next month The Campaign for Drawing will stage The Big Draw; an annual line-up of free events designed to get people putting pen to paper in an artistic style. This year has seen an increase in the campaign's international profile, with Big Draw events taking place in Australia, the Falkland Islands, Canada, USA, Hungary, Italy and Singapore.

Launched in 2000 by the Guild of St George, a small charity founded by the Victorian artist and writer John Ruskin, The Campaign for Drawing works to raise the profile of drawing; promoting its value as an effective tool for perception, invention and communication. Its long-term ambition is to change the way drawing is perceived and used by professionals and the public. Ruskin's writings on art, architecture, natural history and social and economic issues are central to the campaign's project. He saw drawing as a means of connecting with the environment and a way of opening up our eyes to the world around us. "I believe," he wrote, "that the sight is more important than the drawing; and I would rather teach drawing that my pupils may learn to love nature, than teach them looking at nature that they may learn to draw."

In 1871, Ruskin set up the Guild to assist the liberal education of artisans and in turn, the Guild initiated the campaign to celebrate its founder's centenary and to promote his belief that drawing is key to understanding and knowledge. Our relationship to drawing changes with age. For young children, drawing is as natural as playing. They draw the world around them, what they encounter and how they see things. Sketchbooks are filled with images of redbrick houses with billowing chimneys, smiling stickmen and summer skylines.

At a certain age, however, most of us stop drawing. We change from free, expressive artists into individuals with set ideas about our capabilities. But why is that? "Schools offer drawing as an independent subject," says the campaign's director, Sue Grayson Ford. "It becomes something that is used only in the art room and isn't valued it in its wider applications: diagrams, charts, geographical maps and design. The campaign believes that everyone can - and should- draw."

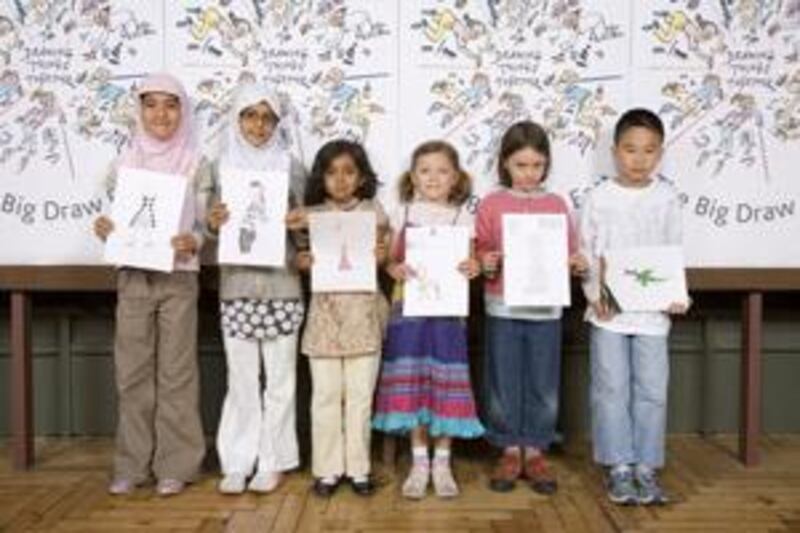

Putting this view into practice, the campaign will stage The Big Draw at over 1,000 venues nationwide, welcoming audiences to a series of free, intergenerational and intercultural events. The usual boundaries of drawing are stretched with events using paint, charcoal, sand, clay, digital imagery and vapour trails. By using all of these different methods, the campaign aims to illustrate that drawing is about more than sketching. One of their stated aims is to promote the perception of drawing as "an important tool for learning, creativity, enjoyment, and social and cultural engagement - a basic human skill used by everyone in all walks of life".

Highlights of The Big Draw are set to include Now We Are Ten, an exhibition celebrating the campaign's first decade, with commissioned works by well-known and up and coming illustrators, designers, cartoonists and artists including Quentin Blake, Steve Bell, Adam Dant, Nicholas Garland, Chris Orr, Paula Rego, Gerald Scarfe and Posy Simmonds. Elsewhere, visitors get creative at the Royal Academy of Arts, draw aircraft models at the Royal Air Force Museum and take part in cartooning workshops and see underwater drawing at the National Marine Aquarium, demonstrating that drawing can be a shared public activity as well as a private passion.

Venues range from museums, galleries and castles, to parks, schools and village halls. "Collectively they show that drawing is a universal language connecting generations and cultures," says Grayson Ford. For graphic designer Thomas Hipwell the Big Draw project is about showing people that drawing isn't just a hobby, but a prerequisite for a number of creative careers. "Drawing is central to my work. If the drawing fails, the project fails. Clients want to see how things will look and I use sketches to give shape to my imagination. It's about precision and focus. It's a great transferable skill."

The artist William Taylor believes that drawing is all about training and retraining the eye to copy what you see. "You don't get drawings right the first time," he says. "But you rub out the imperfections and try and capture it again. A good drawing is a series of corrected mistakes." For Nancy Shakerley, a community worker, The Big Draw provides an opportunity to unite people. To date, the initiative has encouraged over a million people to start drawing again. In the process, it has picked up two world records - for the longest drawing in the world, measuring one kilometre, and the greatest number of people drawing simultaneously, which hit over 7,000.

Running projects with local children aged six to 11 and individuals aged over 60, Shakerley asked participants to draw images from the local environment and used them to create a mosaic that is now displayed permanently in the local community centre. "Not only did it make them think about their surroundings, but it drew them together as a community. Now they have a monument to their creativity and a reminder of the fun they had during the project. Let's hope that this is a catalyst for long-term community cohesion," she says.

Changing the way drawing is perceived by the public and educationalists is one of the greatest challenges facing the campaign. With increasing use of recording equipment and computer graphics, drawing has become a dying art form for some, while others believe that it still marks the zenith of artistic expression. "It's so utterly annoying when you go into a museum or exhibition and find people snapping pictures of works with their iPhones", says the art historian Aimee George. "Yet somehow, when you happen upon someone sketching in the sculpture gallery, it's nicer. I feel like they are appreciating the art the way it was meant to be appreciated. After all, drawing is one of the most rudimentary forms of art-historical study. There is no substitute for sketching, it forces you to explore a work in the tiniest detail."

"The art world is swinging back in favour of drawing," says Grayson Ford. "When you visit an exhibition, the biggest crowd always gathers around the drawings, because they are the most direct medium of expression and communication. If you want to know what motivates an artist, it's all there in the drawings."