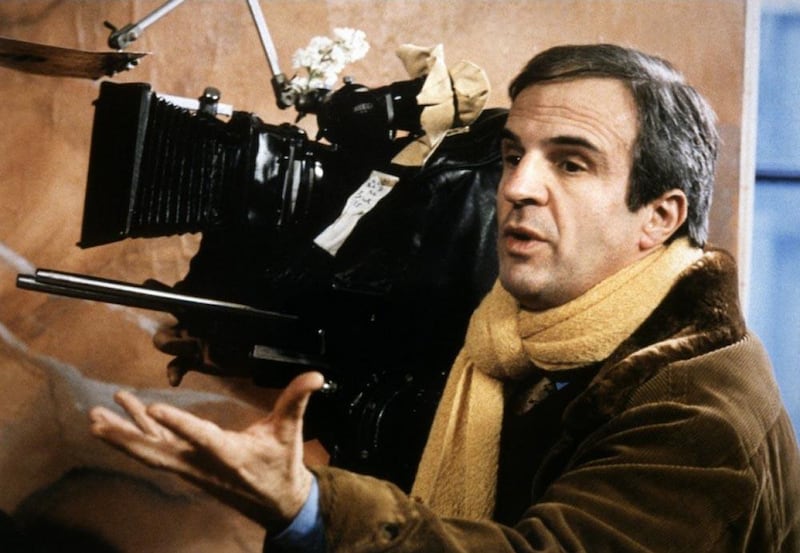

As a special programme celebrating the career of legendary French director François Truffaut – who died 30 years ago this week – opens at the Abu Dhabi Film Festival, Rob Garratt looks at how much of the man can be seen in his movies

“Film lovers are sick people,” François Truffaut once infamously declared, according to film legend.

His argument was that people who love life, live it. Film fans, meanwhile, are “neurotic” escapists. Because “when you don’t love life,” the director muses, “or when life doesn’t give you satisfaction, you go to the movies.”

On another occasion, during a 1961 interview with French television, Truffaut was asked whether he had any interests aside from cinema. “No, I really don’t think so,” he said. “Cinema fills my life completely.”

So what does that say about the director, a man who not only devoured movies, but made them too? A man who also once declared that “three films a day, three books a week and records of great music” would be enough to ensure his happiness until the end of his life.

Typically dealing with themes of adolescence, alienation, thwarted relationships and death, Truffaut’s work – which is celebrated by ADFF with a special programme of seven of his films beginning on Saturday – drew readily on the director’s troubled life.

Formative years

Born in 1932, the only child of an unmarried mother, Truffaut spent his early years under the care of a wet nurse and was eventually taken in by his grandmother close to his third birthday.

Despite taking the surname of his adoptive father, he was only reluctantly welcomed into the family's Paris apartment at the age of 10, after his grandmother's death – experiences that informed his cinematic debut The 400 Blows (1959), a recognised classic, and one of the seven films being screened during ADFF.

Excluded from school at the age of 14, Truffaut turned to cinema for solace, sneaking into a self-prescribed curriculum of three screenings a day. It was a golden age, with a reported 400 screens in the French capital, and the post-War period saw the sudden arrival of a decade’s worth of Americancinema that had been absent during the war years, including medium-defining classics from John Ford, Howard Hawks and Truffaut’s biggest hero, the British director Alfred Hitchcock.

But cinema alone couldn’t keep the adolescent Truffaut out of trouble. While accounts differ as to the exact nature of the crime, while still a teenager he was jailed for three months in a young offenders’ institute – another experience he drew upon and relived in his harrowing debut.

Finding a voice

Life improved little for Truffaut in his early 20s, twice attempting suicide in 1940. After joining and deserting from the French army, he spent much of the next year in military jails and psychiatric units.

Eventually securing a discharge, and offered shelter and support by André Bazin, the influential film critic, he turned to his benefactor’s profession for work.

At this he excelled, publishing close to 700 articles during the 1950s for influential titles Cahiers du Cinéma and Arts-Lettres-Spectacles, known for expressing often controversial opinions in a clear and justifiable way.

His work advocated the influential autuer theory – the idea that a body of work should reflect the director’s overarching creative vision, in spite of commercial demands – which was ultimately adopted as the manifesto of French New Wave, of which Truffaut was a key member alongside Éric Rohmer, Claude Chabrol and Jean-Luc Godard.

Bed and Board

Following the widespread critical and commercial success of his debut film, Truffaut spent the 1960s experimenting with a run of features that, despite their wide variety, all bear the imprints of their director’s life.

His second film was the experimental, freewheeling noir-pastiche Shoot the Pianist (1960), whose tainted hero can again be seen to echo Truffaut – a talented but shy artist who longs for love but is intimated by women.

However it was Jules et Jim (1962) that really caught the public imagination. A warm and offbeat comedy about two men who fall in love with the same woman, it was a rallying cry against the moral code of the day. Less well-known, however, is the fact that the film – also screening at ADFF – was, like its successor The Soft Skin (1964), inspired by a real-life love triangle that began the deterioration of his 1957 marriage to Madeleine Morgenstern.

The Man Who Loved Women

In this context, it is not clear whether 1977's self-written The Man Who Loved Women – based on the fictional memoirs of a notorious womaniser who suffers depression because he is unable to commit to a single partner, and screening at ADFF – should best be viewed as knowing self-awareness or a sad celebration of outdated values.

Notably it was released six years after Truffaut suffered a nervous breakdown, sparked by the end of a three-year romance with the French actress Catherine Deneuve – a the relationship that was the inspiration for his penultimate film, 1981's The Woman Next Door).

Life and death

At the other end of the emotional spectrum lies The Green Room (1978), an adaptation of Henry James' The Alter of the Dead, in which Truffaut plays a bitter obituary writer.

Inspired by the then recent deaths of friends Roberto Rossellini and Henri Langlois, and by Truffaut’s rewatching Shoot the Pianist and realising half the cast had died, the protagonist’s home is decorated with portraits of deceased figures from Truffaut’s own life.

Two other movies screening during ADFF were also inspired by Truffaut's formative years: The Last Metro (1980), named in reference to a citywide curfew, is based on his memories of growing up during the Second World War, while Small Change (1976) focuses on a group of children growing up in rural France, preaching resilience in the face of injustice.

Full circle

But arguably, it is Truffaut’s celebrated “Antoine Doinel cycle” which draws the most from the director’s own life.

Revisiting the protagonist of The 400 Blows a decade later with 1968's Stolen Kisses, we meet a young man making his first forays into the world of romance.

By 1970's Bed and Board, dear Doniel is happily married – until he pursues an affair with an exotic Japanese woman. This draws once more on Truffaut experiences of married life. By 1979's Love on the Run, the couple are getting a divorce – a mistake its director only made once, vowing never to marry again after legally separating from Morgenstern in 1965 having fathered two daughters.

Truffaut’s last great love was Fanny Ardant, an actress who appeared in his two final films. Despite never living together, the couple began a relationship in 1981, and had Truffaut’s third daughter in 1983.

Less than a year later on October 21, 1984, Truffaut died at the age of just 52, 15 months after a brain tumour had been diagnosed. Today Truffaut is counted among the best-loved and most-influential European directors.

The best of the best

The 400 Blows (1959)

An intensely wrought and deeply autobiographical story of a neglected adolescent who is jailed for petty theft, Truffaut’s debut was a critically acclaimed masterpiece feted by critics then and now, and a commercial hit that established his name and talent worldwide.

The closing shot – a heart-jolting freeze-frame of the protagonist on a beach, caught in time, his future undetermined – has been mimicked countless times, but never with such emotional clout.

Truffaut’s contemporary, Claude Chabrol, called it “the best first French film in the history of cinema”, and Truffaut won the Best Director award at Cannes – a year after he had been banned from the festival for critiquing the established order in print.

Vox, Tuesday, October 28, 9.30pm.

The Wild Child (1970)

Truffaut's ninth feature was, significantly, the auteur's first lead role in front of the camera – the beginning of a patchy acting career that culminated with a Hollywood starring role in Steven Spielberg's Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977).

In The Wild Child, Truffaut plays Dr Jean Itard, the true-life physician who devoted years of his life to the study and rehabilitation of Victor of Aveyron, a 12-year-old boy found living wild in the French countryside in 1798.

Vox, Friday, October 31, 7.30pm.

Day for Night (1973)

Named after a cinematographer’s trick for shooting daytime scenes after sundown, Truffaut’s 13th movie ranks among the best ever made about filmmaking.

His only Oscar winner (for Best Foreign Language Film) and the recipient of a Bafta Best Film award, it charts the off-screen dramas affecting the cast and crew during the shooting of a cliched script, with Truffaut playing the director.

Celebrated British novelist Graham Greene makes a cameo appearance, unbeknown to Truffaut at the time.

One notable detractor, however, was comrade Jean-Luc Godard, who made his feelings clear in a blunt letter to Truffaut – to which he received a vitriolic 20-page reply, beginning a lifelong feud between the former brothers in arms of the French New Wave.

Vox, Saturday, October 25, 8.45pm

Also screening: Jules et Jim: Sunday, October 26, 9.30pm; The Last Metro: Thursday, October 30, 9pm; The Man Who Loved Women: Wednesday, October 29, 9.15pm; Small Change: Saturday, October 25, 3.30pm. All screenings at Vox.