Osama bin Laden once dreamt English journalist Robert Fisk was riding on a horse and converting to Islam. That is only one of the many extraordinary tales to be found in This is Not a Movie, Canadian director Yung Chang's documentary that looks at the life and work of Fisk, who was described by The New York Times as "probably the most famous foreign correspondent in Britain".

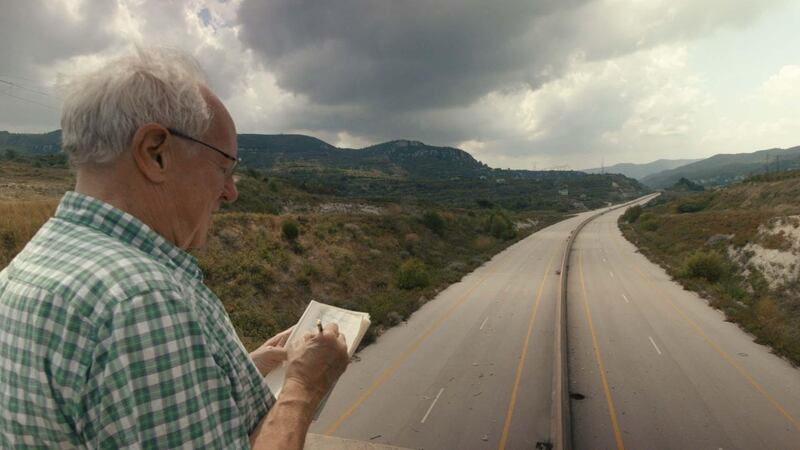

Fisk has been stationed in Beirut since 1976, reporting on the Middle East for The Times before joining The Independent. The film follows him as he goes about his work for the latter newspaper, notepad and pen in hand. He travels to the Syrian front lines in Idlib, investigates a reported chemical attack in Douma and takes a Palestinian national back to land confiscated by the Israeli government. Fisk is also seen in Serbia investigating the sale of weapons used in conflicts in the Middle East, buying books in Beirut and delivering lectures.

The film combines archival footage and images of Fisk, working in Northern Ireland in the 1970s and covering events such as the 1982 massacre at the Palestinian refugee camps of Sabra and Shatila.

The film, which had its world premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival last year, is screening this week at the Copenhagen International Documentary Festival, known as CPH:DOX, which has taken part of its programme online because of the coronavirus outbreak.

The film starts in the manner of an action movie, with Fisk on the front lines of the Iran-Iraq War in 1980, running from Iranian fire. A sound edit moves the action into a car in which Fisk is a passenger travelling through Homs in 2018. It's difficult to tell the difference between the destroyed buildings that serve as a backdrop. The past is intertwined with the present, connected by the words of the reporter. "I wanted to use this as the beginning because it put Robert specifically in the war zone," Chang says.

Fisk describes his fascination with the Middle East as being similar to reading a Tolstoy novel, except the real-life tragedy he sees never ends. Fisk has written books about the Middle East, Ireland and about his father, whom he describes as stubborn. He fell out with his father and chose not to visit him on his deathbed, a decision he regrets. In hindsight, he sees how that relationship fuelled his desire to pick apart arguments and seek the truth.

Chang says he wanted to make the film because of his interest in news reporting in the digital age. "It really started with my feeling of being inundated and overwhelmed by information and the 24-hour news cycle," he tells The National at the film's premiere. "It's so hard to navigate, to know what is true and what is false. I thought that a film like this could sort of be the reset button to stop and think about the nature of journalism through Robert's eyes."

But Fisk was not so sure. He didn't particularly enjoy making the three-part 1993 series From Beirut to Bosnia for Channel 4. "I find it very problematic that directors, especially in those days, started out with a very defined idea of the narrative they wanted to tell and I got tired of that," he says.

But he wasn't against the idea of trying again and

Fisk enjoyed Chang's 2007 documentary Up the Yangzte, so he agreed to meet the filmmaker in Beirut. "Yung knew nothing about the Middle East," Fisk recalls. "What was interesting is that most journalists who arrive in the Middle East tell everyone what they think, but Yung was quiet. He just listened."

Fisk was impressed, but he had a set of rules for Chang: "You follow me around and film, don't ask me to revisit shots," Fisk says. "Don't stop shooting unless there is some particular reason for me to say stop, which there was on one occasion when I knew a European military officer in Sarajevo would not talk to me in the presence of a camera."

These rules defined Chang's approach to the film. He used hand-held cameras so the crew could stay nimble.

"Walking around Beirut, I realised Fisk is the kind of guy for whom a street is not a street, it is a place of history," he says. "Where history intertwines with the present is very consciously part of the way Robert thinks and that informed the structure of the film."

Chang's work provides an insight into journalism today and shows what Fisk is prepared to do for the story, taking a look at situations himself and reporting what he sees. In today's world of fake news and misinformation, it is a lost art.

This is Not a Movie is screening online for CPH:DOX, which runs until Sunday, March 29