"Ahuge thing that has happened in Gaza – and the world's media has done this to some extent – is that the population has been dehumanised," says Irish filmmaker Garry Keane.

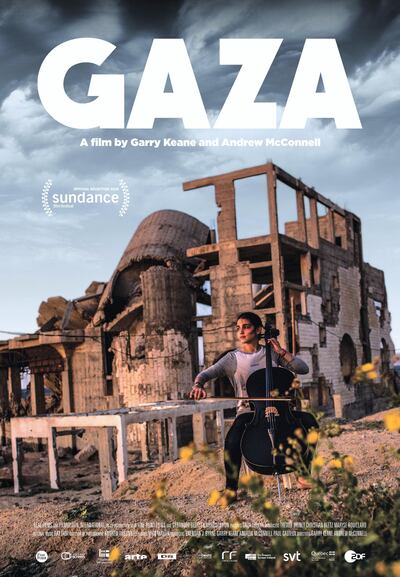

It is a sentiment that forms a central theme of his new documentary, Gaza, which premieres today at the Sundance Film Festival, and is co-directed by photographer Andrew McConnell, who lives in Beirut.

'It's not a war film'

The documentary is a vision of Gaza told through the stories of the people living in the strip – from the 2014 Gaza war to the Great March of Return last year, which called for the right of return for refugees. But this is not a documentary about war or struggle. Instead, it's a film about life, focusing on the strength of the human spirit in a land 40 kilometres long and 11km wide. It is where more than 80 per cent of the population rely on humanitarian aid and that the UN says will be unliveable by next year.

"It's not a war film," explains McConnell. "But you can't avoid the conflict when you're making a film about Gaza, because even though fighting only happens a small percentage of the time, it still permeates everything within the society, so it's crucial to show it."

The genesis of the documentary began in 2011 when multi-award-winning photographer McConnell went to Gaza to take pictures of surfers. The next year, Keane contacted McConnell to ask about collaborating on a documentary about Irish photojournalists working around the world.

When McConnell mentioned the photos of the surfers, Keane's ears pricked up. They changed course immediately and began discussing working together to make a movie about surfers in Gaza.

"I first went in July 2014 to film some of the surfers," says McConnell. "And then, of course, war broke out [on July 8] and everything went out of the window."

Wanting to show a different side of Gaza

McConnell thought the conflict would last only a few days. But for 50 days he was taking photos and shooting footage. He also met locals such as a young boy named Ahmed, and an old fisherman Abu Amer Bakr, who would both become pivotal parts of what morphed into a study of a land told through the testimonies of Gaza residents.

"We wanted to make a non-political film," says Keane. "I think we can be held accountable, that we told it purely from a Gazan perspective, but that's the decision we made from day one. We were never going to cross over and try to create a platform for those of different opinions fighting each other."

The film documents the fishermen, who are only allowed to go 4.8km into the open ocean before they are stopped by Israeli gunboats, effectively stopping them from locating any fish. It also highlights the plight of the tailors who can only work their sewing machines in the sporadic hours when electricity is working. A taxi driver and a woman talk about how society has become less liberal. A young teenager talks of when she will wear the hijab. Then there is the man with 40 children.

"Normality is what we are showing in the first half hour of the film," says Keane. "No matter what happens to them, we find a huge resilience and huge determination among the people of Gaza to create some semblance of normal life."

Keane is quick to interject. "Isn't that a terrible indictment of the situation, that Andrew says we show normal lives to surprise people," says the Irishman. "And then we slowly start to see the realities that stop them being able to do normal things."

From their own personal experiences

Gaza was described by former British Prime Minister David Cameron as an "open-air prison" hemmed in by closed borders to Israel and Egypt. That has made it incredibly difficult for two Gaza residents heavily involved in the film, Ali Aby Yaseen and Fady Hanouna, to go to the United States to meet with audiences.

The directors know from bitter personal experience what happens when barriers are put up between people. "Andrew and I hadn't met before embarking on this project," explains Keane. "Yet we grew up only 15 miles apart from each other, he was in Northern Ireland and I was in the Republic of Ireland. We never really focused on it in terms of an occupation thing, but I suppose we lived those lives growing up, where Andrew lived on one side of the border and I lived on the other."

McConnell recalls encountering checkpoints on trips to the beach. "During the summer we would go to the beach where Gary grew up in County Donegal," he says. "You had to go through the military checkpoints, then you go through customs and then through the Irish police checkpoints on the other side. So that was a regular event for us every summer growing up."

The photographer says that such an experience helped them to understand the emotional state of the protagonists in the film. "There were events that took place in my youth, there was a huge level of violence, there was a massive bomb in Enniskillen in 1987," he says. "But what I found surprising about growing up there was when I spoke to people from the outside world, they would always say: 'Are you not afraid, how do you live?'

"But the majority of time nothing happened there, a large part of daily life is normal."

Gaza has its world premiere at the Sundance Film Festival today